The rain is pouring outside Caz McLeary’s cabin window on the Beira D oil rig when Still Wakes The Deep begins. Gray, miserable, and stationed within the North Sea’s neverending nothingness, this is about as good as it gets onboard the metallic monolith located somewhere off the coast of Scotland.

Water features heavily in the game’s anxiety-filled, mid-70s-inspired storytelling. The “otherworldly horror” release from The Chinese Room – makers of Dear Esther and Everybody's Gone To The Rapture – is set in a tiny chunk of this 575,000 km² ocean, where events are about to take a decidedly unexpected turn “on the edge of all logic and reality”.

In fact, while lead character McLeary – seeking to escape the police, his family, and the general oppressions of life – is faced with an undisclosed and rather more terrifying cosmic foe, he must also conquer these environmental forces in his attempts to stay alive. “Water was always meant to be our second enemy,” explains the Brighton-based studio’s lead designer Rob McLachlan in framing what players can expect when the horror game launches this month.

“The North Sea is not a glamorous place. It's shallow, which makes it very rough. It obviously has a long history for the British Isles, right back to its identity as Doggerland in prehistoric times and as a place of commerce and war through all the states that existed around the shores,” McLachlan tells us.

He's keen to point out this is not “the traditional tropical blue sea” you might have seen in other video games. “It’s where we could differentiate ourselves. This is a grey ocean filled with sediment. It's unknown and unknowable. You can't see through it. It's a blank slate that you exist above. The windblown level beneath is like some sort of eternity.”

Nightmare before Christmas

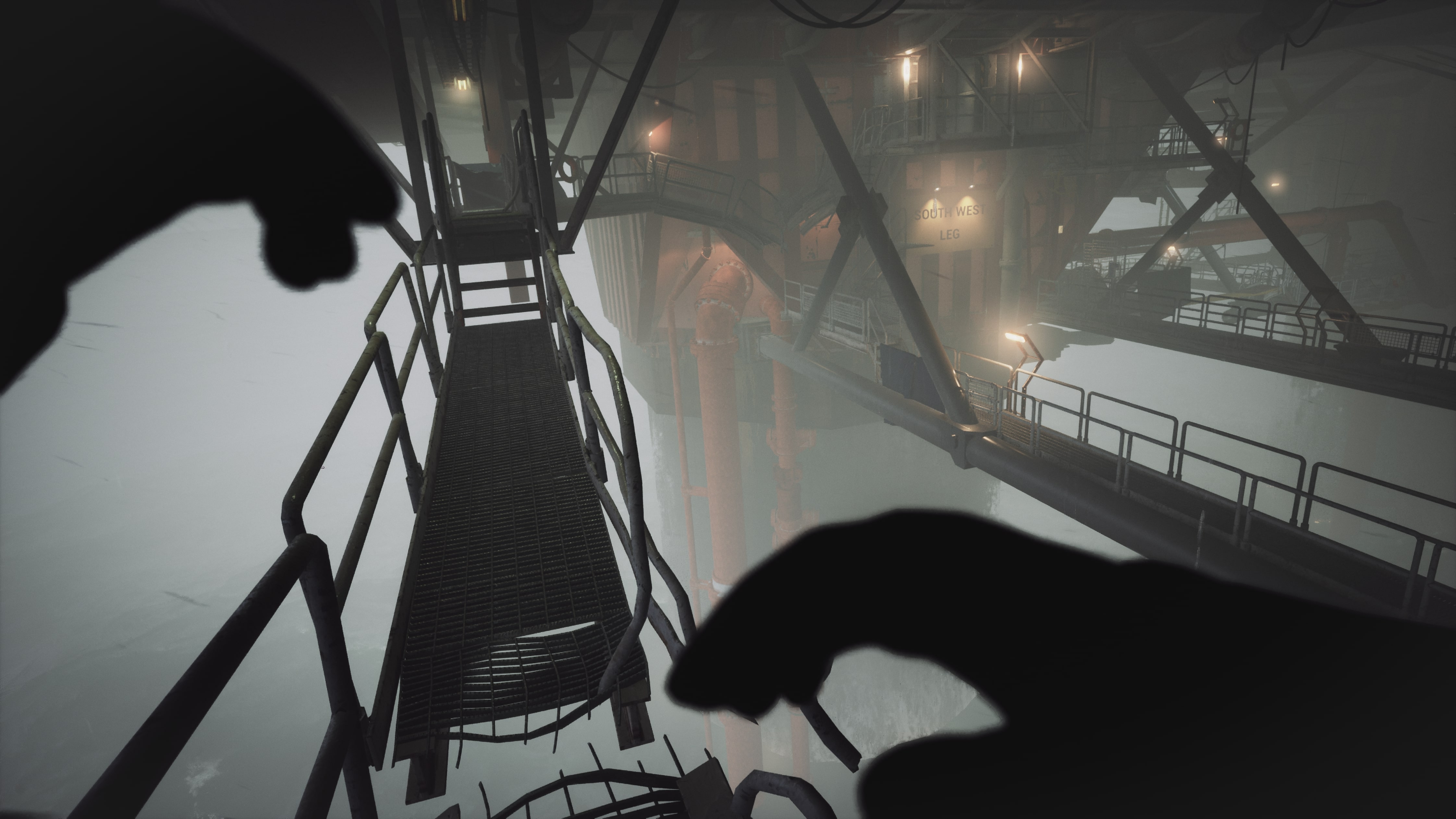

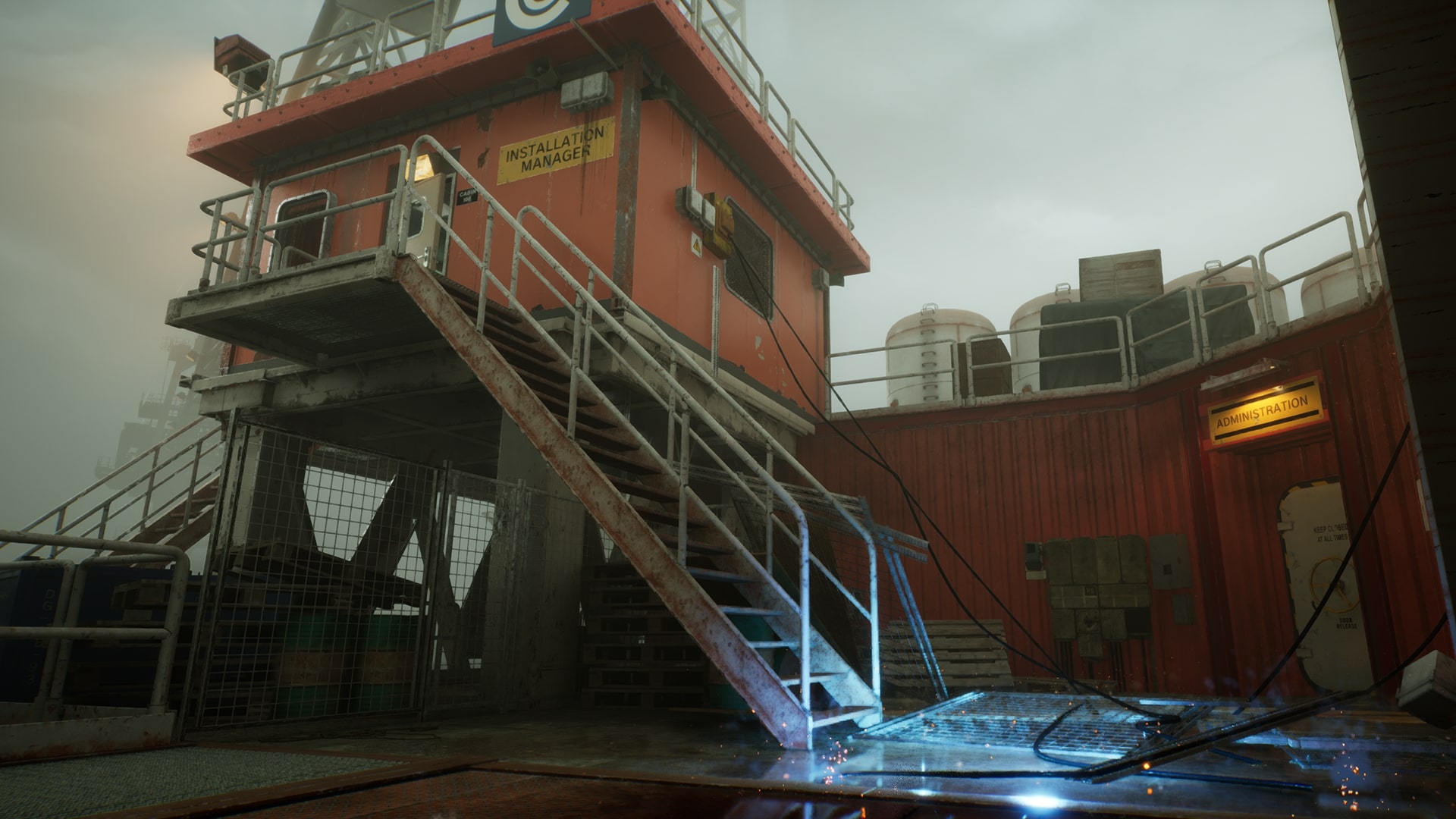

In the opening scenes, this sense of place is profoundly realized not only by the agreeably dreich conditions but also by the compelling context and historical accuracy of the immersive world-building. In first-person perspective, you are initially tasked with guiding Glaswegian boxer-turned-electrician Caz around the rig to engage with other members of the crew. Festooned with festive decorations – the game is set at Christmas – this initial phase illuminates the tangible attention to detail that underpins the player experience.

A handwritten list of prospective jukebox tracks chosen by those onboard from the likes of David Bowie, 10cc, AC/DC, Wings, and Rod Stewart is taped to the wall of the crew lounge. McLeary’s choice? Born To Run by Bruce Springsteen, of course. Elsewhere, a Christmas Day menu is on display with dishes that include cullen skink and scotch broth as starters, then a main course of haggis with neeps and tatties, followed by cranachan or perkins.

Conversations in the canteen are conducted in the kind of slang dialect required to make sense of these food options. They center on the decrepit state of the Beira D, potential industrial action over pay, and the emergent threat from other drilling companies, eager to tap into this newfound revenue stream, which is described by one exasperated crew member as “Scotland’s oil”. Meanwhile, outside on the deck, the rig is a windswept, bravura feat in games design, characterized by hard graft, coarse language, and widescreen mechanization.

These gritty realities and socioeconomic pressure points are destined to collide with something far more outlandish, delivering an experience that is founded on reality but powered by fantasy. McLachlan continues: “You're on an artificial island of metal in the middle of a desolate and unforgiving environment. In the time our game is set, it is inhospitable, remote, and a kind of frontier land for both humanity and society. We played on that extensively in terms of our themes of isolation and, to an extent, a new social order, where people who had grown up in Scottish fishing villages became involved in this industry, catapulting the UK into a new era of being.

“Scotland was the sick man of Europe and it was oil revenues that enabled many things: some good, some bad. In the east coast, places like Aberdeen are unrecognizable from what they were before the industry started. We wanted to get that frontier land to accentuate the player's feeling they were in a place no one had ever been before. Like a spaceship but something that was much more graspable and identifiable, so they could see themselves being there and understand the reaction the crew and characters have. The way they react is so integral to the whole theme of the story,” he says.

It's a rigged system, folks

This is a story that first emerged around four years ago when former creative director Dan Pinchbeck pitched a simple premise: “A horror game on an oil rig.” Since then, The Chinese Room team has embellished their canvas with flashes of color from visual entertainment – 70s and 80s kitchen sink TV dramas, alongside films like The Thing and Annihilation – wedded to “a vein of Lovecraftian cosmic horror”. “We've said in the past we wanted to make a movie that starts out being directed by Ken Loach and ends up being directed by Stanley Kubrick. We push it into that extraordinary place as the game progresses,” suggests McLachlan.

The decision to set the game at Christmas further handicaps the player in a multitude of ways. Why was that important? “It's both for practical and atmospheric reasons. A bunch of people go home, there’s a skeleton crew and that means we don't need quite so many on board. That helped because it creates a certain atmosphere and reduces the cost of creating additional crew members. Also, it's an eerie juxtaposition. December is a very dark time up near the Shetlands, where the sun rises late and sets early. It doesn't even get out of nautical twilight.”

Research into this era – reaching across weather systems, health and safety regulations, and urban legends about “what lies beneath” – is tangibly apparent in the uncanny surroundings. The team checked out contemporaneous footage from BP’s archive, watched YouTube urban exploration videos of mothballed oil rigs moored in the Moray Firth and attempts were – unsuccessfully – made to visit decommissioned platforms in Hartlepool and Hull. Interviews with former North Sea oil workers then filled in any gaps.

“We even looked at storm histories,” comments McLachlan. “There was a very strong storm over winter 1975, which we latched on to because it hits the rig at the same time as events happen on board. It's that Marie Celeste atmosphere you get as the game progresses, where parts of the rig go from human spaces with people in to empty and with the pathos of Christmas decorations still hanging. That was gold dust for us atmospherically.”

A death aquatic

Inevitably, this forensic approach informs the water-based components. McLachlan suggests they consulted other titles, like Assassin's Creed and Sea of Thieves – which has received particular praise for its depiction of a fictitious ocean – in their quest for “state of the art” visual fidelity. “But our use case was that we wanted the sea to almost repel you. We wanted you to feel that if you touched it, you would die,” he says.

This version of the North Sea was devised using the Gerstner wave simulator, which calculates the shape and movement of bodies of water in video games. It replicates the ebb and flow of the ocean systemically in alignment with the positioning of the rig. Additionally, the Beaufort scale – a real-world measurement that connects wind speed to conditions at sea – was utilized, adding another dimension of believability. In fact, as McLachlan confirms, the studio team became somewhat obsessed with “the mystery of the sea” during the making of Still Wakes The Deep.

He highlights the “freak wave” that hit the Norwegian Draupner gas platform on January 1, 1995, as an example of their meticulous investigations. Measuring almost 26m, this was evidence of the mind-boggling impossibility of events that have been known to take place offshore. “It was final proof of what sailors had been saying for centuries that sometimes these waves come out of nowhere,” he states. “We loved the idea that this sudden spike can appear out of the chaos of waves and be driven by the intersecting frequencies of the water to create this terrifying thing that can sink a ship, destroy a lighthouse, or wash people away in seconds.”

In the build-up to the release of Still Wakes The Deep, The Chinese Room has remained tight-lipped about the cosmic adversary that awaits players. But there is no camouflaging the threat posed by the environment surrounding the Beira D. “Every time you look out of a window, every time you look over the side, it's there,” says McLachlan. There’s more bad news. “The rig evolves over the course of the game. It tilts and sinks and the water comes in. You can't escape it. It will get you,” he promises.

Still Wakes The Deep is out on June 18 on PS5, Xbox Series X, and PC.

You might also like...

- Our rundown of the best indie horror games

- Get the right tool for your games with our guide to the best PC controllers

- A closer look at the next in a popular stealth series in our Assassin's Creed Shadows preview