Nigeria, like many other Sub-Saharan Africa countries, has a waste management problem. The Nigerian National Municipal Waste Management Policy (2020) gives no estimate but states that “Nigeria produces a large volume of solid waste out of which less than 20% is collected through a formal system”.

This is lower than the World Bank’s estimate of average waste collection for Sub-Saharan countries, which is 44 percent. It also contrasts with the European and North American collection rate – 90 percent of waste generated.

The problem is not only how much waste is collected but the lack of accurate data about how much waste is being generated in the first place. The Lagos State is a good example. Nigeria’s most populous city generated 10,000 tonnes of waste per day in 2005. And the Lagos State said in 2018 that the amount of waste generated then far “outweighs the official figure of 13,000 tons per day”.

Managing this waste, from collection and transportation to disposal, is a major challenge for Lagos, which accounts for a large proportion of Nigeria’s waste. The population of Lagos state, urbanisation, consumption patterns and the scale of economic activity work together to increase waste generation.

The Nigerian National Municipal Waste Management Policy (2020) has the potential to transform waste management around the country.

The policy proposes a system to separate, recycle and treat waste, conserve natural resources and create opportunities to earn a living from waste.

But the policy hasn’t been fully implemented.

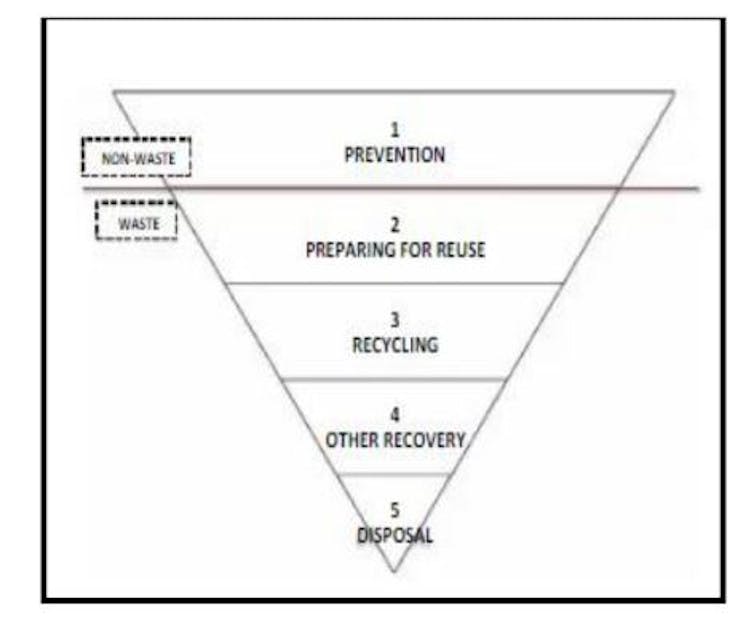

In a recent article, my colleagues and I wrote about the need for Lagos State to put in place a strong policy framework that incorporates waste hierarchy guidelines. The waste hierarchy is the idea that the things we do to waste aren’t equally desirable. First should be prevention; then reuse, recycling, recovery and (least desirable) disposal.

We found that in Lagos, this hierarchy wasn’t being followed. Residents generate mixed waste without separation or sorting. Households store their waste primarily in plastic bags, sacks and buckets. Contracted waste collectors collect mixed waste and transport it directly to dumpsites. Waste pickers at dumpsites recover valuable materials and waste is burnt at these sites.

In practice, the waste hierarchy has been turned upside down in Lagos State. Waste is not being collected, transported, recovered and disposed of in a sustainable way – one that does not endanger the environment, human health and future generations.

How Lagos collects waste

The Lagos State Waste Management Authority was set up in 1991 to collect, transport and dispose of municipal and industrial waste.

In recent times, the authority has deployed street sweepers and improved open dumpsites. It introduced 102 waste collection trucks and the Adopt-A-Bin programme, under which households and businesses can buy their waste bins. It started the Lagos Recycle initiative using a smart waste collection and reporting software application, and has invested in equipment to manage dumpsites.

It launched the Blue Box Initiative, which aims to promote the culture of sorting waste at the point of generation. However, this initiative has crumbled.

Ongoing initiatives to raise social awareness about environmental issues include summer school for students and sanitation advocacy.

However, Lagos continues to produce a large quantity of waste without adequate mechanisms for managing it.

Weaknesses in waste management

The majority of Lagos residents are not aware of the environmental importance of waste separation and sorting. This should be the first step in a sustainable management system.

The prices of the individual waste bins provided by the Lagos waste authority, which is supposed to promote waste separation and sorting, are too high. For this reason, some residents (especially from low-income families) use plastic bags, sacks and buckets instead of bins.

Also contributing to poor waste management in Lagos State are:

irregular and sporadic collection

residents’ unwillingness to pay

the collapse of the materials recovery and recycling facility (Olusosun buy-back facility)

open burning at dumpsites, which endangers lives

dangerous conditions for street sweepers on roads and highways

inadequate funding

poor technology

weak policy framework

inadequate social development

inconsistencies in enforcement and monitoring.

Improving waste management in Lagos

The Lagos State Waste Management Authority needs to identify the most appropriate waste streams (multiple, single or dirty recycling) according to the income level of residents. The multiple recycling stream means that several bins are provided for the collection of different recyclable materials. A single recycling stream involves collecting all recyclable materials in a single bin. Dirty recycling streams put all waste in a single bin without sorting and separation.

The multiple stream is most suited to high-income areas and the dirty stream more practical for low-income areas.

The dirty recycling system is similar to the practices of cart pushers who collect unsorted waste from households in wheelbarrows. The difference is that residents can dispose of their waste in a bin of their choice for a fixed fee (pay-as-you-throw) in waste collection vehicles assigned to their area.

The Lagos State Waste Management Authority, policy makers, waste collectors, community representatives, residents and other relevant stakeholders decides which waste belongs in the 3-in-1 and 2-in-1 bins and sets the bin prices for the pay-as-you-throw system after proper consultation.

Street sweepers and waste pickers should become city employees. Sweepers should be replaced by sweeping trucks with appropriate training.

Dumpsites should be upgraded to landfills. Appropriate technologies and digital solutions should be adopted. And people should be made aware of waste separation and sorting through the school curriculum, social media, television, radio and billboards.

Equally important are prudent financial management, bin incentives and government financial aid for private individuals who want to get into waste management. The system also needs consistent enforcement and monitoring. Above all, this is a template that can be replicated in other parts of the Nigerian state.

Kehinde Allen-Taylor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.