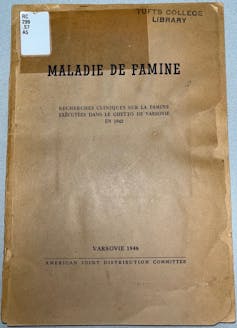

Exactly 80 years ago, a group of starving Jewish scientists and doctors in the Warsaw Ghetto were collecting data on their starving patients. They hoped their research would benefit future generations through better ways to treat malnutrition, and they wanted the world to know of Nazi atrocities to prevent something similar from ever happening again. They recorded the grim effects of an almost complete lack of food on the human body in a rare book titled “Maladie de Famine” (in English, “The Disease of Starvation: Clinical Research on Starvation in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942”) that we recently rediscovered in the Tufts University library.

As scientists who study starvation, its biological effects and its use as a weapon of mass destruction, we believe the story of how and why Jewish scientists conducted this research in such extreme conditions is as important and compelling as its results.

The clandestine project’s lead doctor, Israel Milejkowski, wrote the books’s foreword. In it, he explains:

“The work was originated and pursued under unbelievable conditions. I hold my pen in my hand and death stares into my room. It looks through the black windows of sad empty houses on deserted streets littered with vandalized and burglarized possessions. … In this prevailing silence lies the power and the depth of our pain and the moans that one day will shake the world’s conscience.”

Reading these words, we were both transfixed, transported by his voice to a time and place where starvation was being used as a weapon of oppression and annihilation as the Nazis were systematically exterminating all Jews in their occupied territories. As scholars of starvation, we were also well aware that this book catalogs many of the justifications for the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which made starvation of civilians a war crime.

A defiant medical record

Within months of their 1939 invasion of Poland, Nazi forces created the infamous Warsaw Ghetto. At its peak, more than 450,000 Jews were required to live in this small, walled-off area of about 1.5 square miles (3.9 square kilometers) within the city, unable to leave even to look for food.

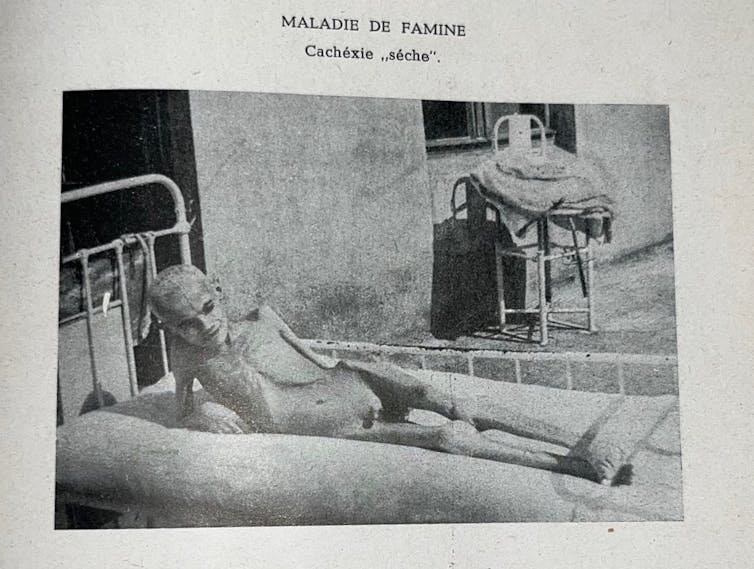

Although Germans in Warsaw were allotted a daily ration of about 2,600 calories, physicians in the ghetto estimated that Jews were able to consume only about 800 calories a day on average through a combination of rations and smuggling. That’s about half the calories volunteers consumed in a study on starvation conducted near the end of World War II by researchers at the University of Minnesota, and less than a third of the average energy needs of an adult male.

When the Nazis designated the district of the Warsaw Ghetto, it enclosed two hospitals, one serving Jewish adults and another for Jewish children. The hospitals were allowed to continue to treat patients with whatever resources they could obtain, but Jews in general were forbidden from conducting research. Nevertheless, starting in February 1942, a group of Jewish doctors in the ghetto defied their captors by meticulously and secretly gathering data and observations on multiple biological aspects of starvation.

Then on July 22, 1942, Nazi forces entered the ghetto and destroyed the hospitals and other critical services. Patients and some of the doctors were killed outright or deported to be gassed, their laboratories, samples and some of their research destroyed.

With their own demise approaching, the remaining doctors spent the last nights of their lives meeting secretly in the cemetery buildings, transforming their data into a series of research articles. By October, as they put the finishing touches on the book, about 300,000 Jews from the ghetto had already been gassed. The physicians’ own data showed that another 100,000 had been killed through forced starvation and disease.

With final deportations of the few surviving Jews underway and his own death imminent, Milejkowski wrote of the dark, yawning emptiness of the ghetto at that moment, and the horrifying conditions the doctors had labored under to conduct and record the research.

Milejkowski had words for not only the reader, but also his dear colleagues, many of whom had already been executed.

“What can I tell you, my beloved colleagues and companions in misery. You are a part of all of us. Slavery, hunger, deportation, those death figures in our ghetto were also your legacy. And you, by your work, could give the henchman the answer ‘Non omnis moriar,’ [I shall not wholly die].”

The team’s act of resistance through science was its way to wring something good out of an evil situation, to show the world the quality of the Jewish doctor, but mostly to defy the Nazis’ intent to erase their existence.

With death knocking on the door, the doctors smuggled their precious research out of the ghetto to a sympathizer who buried it in the cemetery of the Warsaw hospital. Less than a year later, all but a few of the 23 authors were dead.

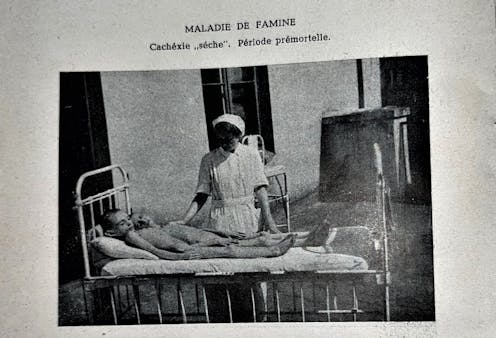

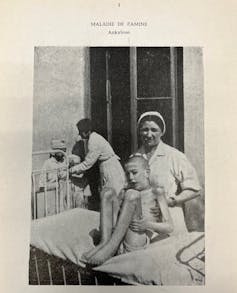

Immediately after the war, the manuscript was dug up and taken to one of the few surviving authors, Dr. Emil Apfelbaum, and the American Joint Distribution Committee in Warsaw, a charity whose main purpose at the time was to help Jewish survivors. Together, they made the final edits and printed the six surviving articles, binding them into a book along with photos taken in the ghetto. Apfelbaum died just a couple of months before the final printing, broken by his years in the ghetto.

In 1948 and 1949, the American Joint Distribution Committee disseminated 1,000 copies of the French translation to hospitals, medical schools, libraries and universities across the U.S. It was one humble, crumbling copy of this book that waited to be “rediscovered” about 75 years later in the basement of a Tufts University library.

The book’s grim descriptions

Based on observations of thousands of deaths from starvation, this research from the Warsaw Ghetto provides insight into the biological progression of starvation that scientists now are just beginning to understand.

For example, many Warsaw Ghetto residents who died of starvation were otherwise free of disease. The ghetto researchers found that while an otherwise healthy body diminished through starvation apparently had a decreased need for vitamins, the need for certain minerals remained. They saw few cases of scurvy (vitamin C deficiency), night blindness (vitamin A deficiency) or rickets (vitamin D deficiency). But they did see significant osteomalacia, a softening of the bones, as the body mined them for their stores of minerals.

When the doctors provided sugar to the severely malnourished, their energy-starved cells quickly absorbed it. This demonstrated that the ability to quickly absorb and use energy remained to the end, suggesting that energy was the single most important factor in starvation, not other micro- or macronutrients.

Each of these observations invites us as scientists to explore further. And with these lessons we can hope to prevent deaths or long-term harm from starvation through better treatment for the severely malnourished.

As scientists studying starvation today, it would be unthinkable and unethical to starve people to learn how the human body adjusts and changes during the end stages of extreme starvation. Even if researchers go into a famine-stricken population to learn about starvation, they immediately treat the victims, erasing the very object of their research.

Partly as a result of the experience of the Warsaw Ghetto, the Geneva Conventions made intentional mass starvation a crime, further strengthened by a U.N. Security Council Resolution as recently as 2018. Nevertheless, this inhumane aspect of war remains to this day, as evidenced by current events in Ukraine and Tigray, Ethiopia.

Though “Maladie de Famine” has never been totally lost or forgotten, the lessons from the doctors’ research have faded to semi-obscurity. Eight decades after the destruction that ended their studies, we hope to shine a renewed light on this work and its enduring impact on physicians’ understanding of starvation and how to treat it. The unique data and observations regarding severe starvation that the Warsaw Ghetto doctors, despite their own suffering, presented in this precious book can even now help safeguard others from that same fate.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.