Propaganda has been an important element in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

What’s been happening in Ukraine since Feb. 24 is seen in a different light and interpreted in different ways, using different terms, depending on where people live. Ukrainian and western media call the invasion a “war,” whereas the Russian media use the term “special military operation.”

Read more: How Russia's unanswered propaganda led to the war in Ukraine

Shortly after the invasion in Ukraine, a new law was enacted in Russia. Since March 4, it’s been a criminal offence to publicly transmit, including by means of social networks, any “deliberately false information about the deployment of the military forces of the Russian Federation.”

The scope of “deliberately false information” includes reporting any casualty figures that depart from the officially approved numbers in addition to using the word “war.”

Russia’s governing elite has learned from their own mistakes about the importance of tight controls on the media. The Chechen wars of the 1990s-2000s showed that without controlling the media, the true situation in war zones becomes known to the public and can be used against those in power.

The knowledge of the true scope of Russian atrocities fuelled anti-war sentiments and protests. The first Chechen war (1994-96) was unpopular from its first moments.

During the second Chechen war (1999-2009) and especially during the Russo-Georgian war in 2008, Russia started to deploy “communication power” in addition to military power.

Russia restricted access to relevant information, releasing it selectively and only to trusted media. The types of propaganda techniques first studied by Harold Lasswell, an American communications theorist, allowed the Russian regime to create an image of the war that would be more acceptable for both domestic and global audiences.

Russia Today, a news channel created in 2005, was instrumental in targeting the international audience. Its estimated budget in 2015 was about $245 million.

Russia Today, in particular, has been particularly keen to exploit blind spots in mainstream media coverage in the West while simultaneously concealing truths uncomfortable for the Russian government.

How propaganda works

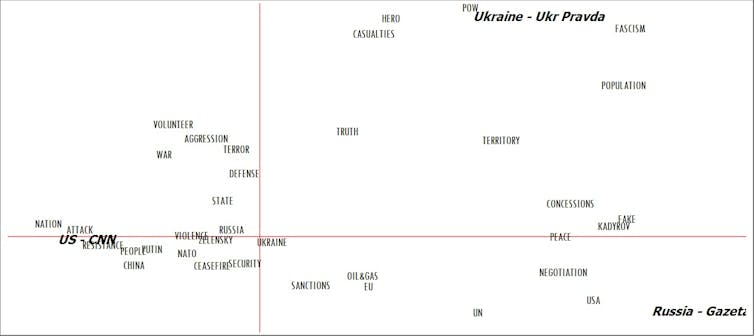

My ongoing analysis of news feeds covering Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows how propaganda works by identifying those blind spots. I analyzed the content of the war reporting of three major media organizations: Ukrainska Pravda) in Ukraine, Gazeta.Ru in Russia and CNN using a mixed-methods approach and a custom-built dictionary that contains Ukrainian, Russian and English terms.

All three media outlets are among the sources of information most often cited in their home countries. The scope of my analysis includes the first month of the war (about 1.4 million words in total in the three languages).

The 10 most used words in the coverage of the war are, starting with the most frequent ones:

Russia

Ukraine

Putin

War

People

Zelensky

Sanctions

NATO

Defence

Oil and gas

Their relative use varies significantly, however. For instance, the word war is notably absent from the news feed of Gazeta.ru. It can be found in different contexts only: “The West started a financial-economic war against Russia,” or an allegation that Meta — the parent company of Facebook and Instagram — “declared an informational war without rules to Russia.”

My analysis shows the relative emphasis placed by the three media outlets in their coverage of the war. The closer a specific term to a medium is placed on the map, the higher the term’s relative frequency in the medium’s news feed. For instance, the relative frequency of resistance, people, Putin, China, attack and nation is higher in the CNN newsfeed relative to the two other newsfeeds.

Ukrainian calls for ‘truth’

It appears that Ukrainian and Russian media devote more attention to the issue of alleged fake news than CNN. The word fake is located halfway between the Gazeta.ru and Ukrainska Pravda markers and far away from the CNN marker.

Even the law banning the use of the word war in Russia has “fake” in its colloquial name: “the law on punishment for ‘fakes’ about the operation of the Russian military has been enacted,” as reported by Gazeta.ru.

Calls for knowing and transmitting the truth are most frequent on Ukrainska Pravda: for example, reports featuring a quote from Taras Shevchenko, a Ukrainian poet: “You have truth on your side” and one from Olena Zelenska, Ukraine’s first lady: “I address to representatives of foreign mass media: keep showing what is happening here, keep telling the truth.”

Mentions of heroes, war casualties and prisoners of war (POW) are notably rare in the Gazeta.ru newsfeed. Instead, the Russian discourse on the war tends to be focused on negotiations, concessions and the role played by the United States in the conflict.

In contrast to Ukrainian media, my analysis suggests Russian media don’t report on war casualties. To comply with the new law, they must wait for official statements — and the Russian government apparently prefers to keep silent on the topic.

When responding to a question on when such information would be forthcoming, Dmitry Peskov, Vladimir Putin’s press secretary, simply said: “When the Ministry of Defense sees fit.” Subsequently on March 25, the ministry assessed them at only 1,351.

Ukrainian sources, however, say Russian losses now exceed the Soviet Union’s losses during the entire 10-year war in Afghanistan, when official Soviet casualties totalled 14,453 dead. NATO has said between 7,000 to 15,000 Russian troops have died in Ukraine since Feb. 24.

If the Russian population is being misled about war casualties, it’s unsurprising they’re supportive of the “special military operation.” In fact, 74 per cent currently back the Russian invasion, an increase of nine percentage points since the start of the war. Surveys further show that Russians are “proud” of the military operation.

Information counter-measures

This situation is hardly new. Soviet leaders were skilled at controlling information flows. In his satirical novel Moscow 2042, Vladimir Voinovich, the late Soviet dissident and writer, imagined that information would penetrate the so-called Iron Curtain — the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate regions from the end of Second World War — by being projected onto the sky.

Today, the internet has become a more practical medium. But the Russian government has learned to control the internet, restricting access to information deemed undesirable.

The Ukrainska Pravda website had been banned in Russia long before the war started. A website with information on Russian troops who have died or disappeared in Ukraine was banned shortly after its launch on Feb. 27.

Dead bodies cannot be indefinitely hidden, however. Eventually news of their deaths will reach the fallen soldiers’ families. And it would hardly be possible for Russian propagandists to argue in that situation that information about the war is just a matter of opinion.

Casualties represent the ultimate reality check. Media reports about them are the most efficient way to expose the truth — regardless of the propaganda efforts my continuing research suggests is ongoing in Russia.

Anton Oleinik does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)