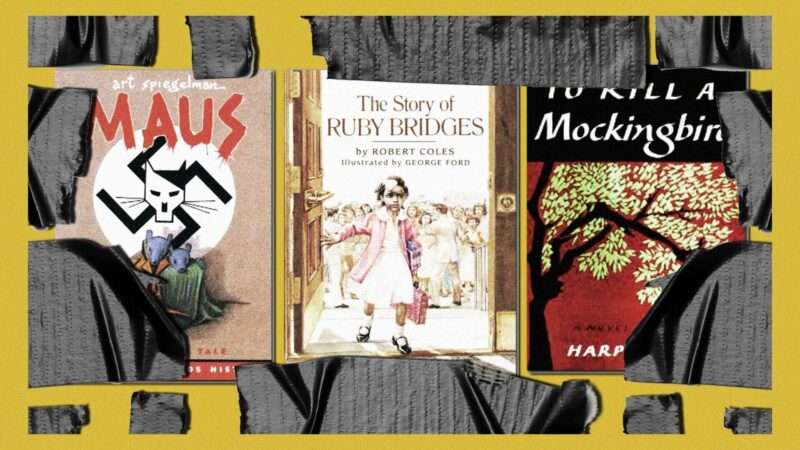

We've all seen the stories: In Tennessee last year, a group called Moms for Liberty challenged the inclusion of age-appropriate, picture-heavy books about Ruby Bridges, the little black girl who desegregated New Orleans schools in 1960 and was immortalized in Norman Rockwell's painting "The Problem We All Live With," in a second-grade curriculum because they "reveal anti-American" and "anti-White" animus.

A different school board in the same state pulled Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel Maus from its eighth grade Holocaust teaching, arguing that its "unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide" made it unsuitable for students of that age.

In the state of Washington, a progressive school board yanked To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) from high school because it perpetuates "white savior tropes" and features characters using racial slurs without being punished for such now-unacceptable language. (This is an interesting turn of events, since Harper Lee's novel has historically been called out for foregrounding age-inappropriate themes of rape, incest, and classism.)

If we're being fair, it's easy to mock all these decisions (what a bunch of goddamn snowflakes!) but also to make a defense of them (how dare you tell my kids what to read!). Schools necessarily do need to be making specific calls about what to include and what to skip, since they can't teach everything. As an overeducated parent of two now-grown sons who has strong (if not always strongly informed) opinions about education, I know what it's like to sift through materials and wonder just what the fuck is going on at your kids' schools. After two years of massively disrupted schooling and overhearing mostly useless Zoom classes, parents are understandably spoiling for fights.

None of what's being discussed is censorship in the remotest sense of the word, since even the "banned" books remain readily available in libraries and bookstores. (In fact, Maus, originally published in collected form in 1991, vaulted to the top of Amazon's bestsellers lists immediately after being challenged.)

But here's the thing: Unless we want to live in a country where every curricular decision—even ones about what's served in the cafeteria—is subject to scorched-earth scrutiny not simply by the relevant parents and (maybe relevant) taxpayers but by every cable news host, Instagram mom, Bean Dad, elected official, and citizen at large, we need to give the people most directly affected more options so they can find a school that works for them.

The problem isn't that To Kill a Mockingbird is being pulled from—or made mandatory in—10th-grade English, it's that the overwhelming majority of kids (and parents) who are being told to suck it have no options. About 91 percent of K-12 students attend public schools, and while there has been a significant increase in various forms of school choice such as charters, online programs, and homeschooling, the overwhelming majority of kids still go to traditional, residential-assignment grammar and high schools.

In a country as vast, diverse, and heterogenous as the United States, there's no way that 98,000 public schools in 13,800 districts are going to please everyone, even if they are doing surprisingly well with most parents. (Even in the wake of COVID debacles, Gallup reports that 73 percent of parents are completely or somewhat satisfied "with the quality of the education [their] oldest child is receiving.") The heart of the matter isn't about who is making what specific decisions (however moronic you or I might think they are) but who is bound by them. Until we give parents not just more input into what their kids are learning but more actual options for where to send their kids, today's book battles are only going to get worse. Gone for good are the days when an easy consensus on just about anything but especially education can be reached. For a lot of mostly good reasons (we're wealthier, more educated, and more skeptical of experts and authorities), all of us feel empowered to insist on our preferences, especially when it comes to education.

The model to achieve peace in education is how religion works in a free society. When there is only one church in town and all must attend, anger and conflict are inevitable, and there are endless struggles to control what gets preached and thus forced down everyone's throat. If you make it possible for thousands of congregations to exist and let people attend the services they want, you'll sow tolerance and pluralism even as folks will continue to debate whose god is best, what is the one and only heaven, and how best to live a meaningful life.

The growing rancor about "inappropriate" content in public schools reflects what the conservative commentator David French calls "the censorship fever that is breaking out across America." Increasingly aggressive challenges to books from the right and the left are the junior varsity version of a broader cancel culture that seeks to regiment public opinion and delegitimize free expression, good-faith argument, and dissent.

None of this new, of course, as schools have always been ideological battlegrounds, often precisely because of the texts in use. In Philadelphia in 1844, disputes over whether the Protestant or Catholic Bible should be used in the city's public schools sparked riots that killed 20 and burned down two Catholic churches. If that sort of violence seems unlikely today, the long history of curricular fights is both comforting (they're nothing new) and depressing (god, not this again).

If there's something particularly dangerous in the attention paid to fights over school libraries stocking Gender Queer and The Kite Runner, it's that they deflect attention from a more serious—and actual—form of censorship at the state level, where legislators, often in the name of empowering parents, are rushing to locate educational decision-making far, far away from neighborhood schools and local control.

The free expression group PEN America says that there's a "steep rise in gag orders," or laws that proscribe teaching certain ideas and concepts at the state-wide level. Such laws are not going to depoliticize culture war battles over what gets taught. Indeed, because they raise the stakes from a particular school or district to a much bigger jurisdiction, they can only pour gas on current fires.

According to political scientist Jeffrey Sachs, over the past year, at least 122 such bills have been introduced in legislatures, a dozen have become law in 10 states, and over 100 are still "live." The vast majority of these target K-12 education, though some also cover state-assisted higher ed institutions. PEN America keeps an updated spreadsheet of the proposals, many of which would ban particular works (never a good sign in a free society), empower a pedagogical version of the heckler's veto, and ratchet up the politicization of curricula to an even more frenzied level.

At least 20 of the bills introduced over the past year specifically ban any classroom use or discussion of the 1619 Project and 11 also ban the teaching of critical race theory (CRT) by name, which is defined by the Florida Board of Education as a set of theories that teach "that racism is not merely the product of prejudice, but that racism is embedded in American society and its legal systems in order to uphold the supremacy of white persons." Another two dozen create a "private right of action" that would allow parents and other citizens to sue schools and districts.

"The alleged problem [of CRT] is so endemic that conservatives typically concerned with government overreach, thought policing, and political correctness now support a top-down legislative crackdown that calls for state control of local decisions, book banning, and a single acceptable story about America's heritage," writes Chris Stewart, a school choice activist and former member of the St. Paul, Minnesota, school board.

The newfound commitment by mostly Republican legislators to the fierce urgency of now has led to embarrassment. In January, a Virginia delegate rushed to pre-file a bill that would have mandated the teaching of, among other sacred texts, "the first debate between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass," which of course doesn't exist. (In 1858, Lincoln famously sparred with pro-slavery Senator Stephen Douglass of Illinois). We could make too much over this detail, for sure, but it's a bad sign when basic facts are wrong in legislation that could have massive reach.

The same bill bans the teaching of "divisive concepts," which everyone will quickly recognize as a series of progressive talking points about systemic racism, the evils of capitalism, and equity of outcome vs. equality of opportunity comprising the colloquial definition of CRT. As someone who disagrees strongly with such thinking, the only thing I find more troubling than it is the state dictating the limits of acceptable thought.

Supporters of state-level gag orders say they merely represent, in the words of the Manhattan Institute's Chris Rufo, parents finally "taking a stand against a broken public school system." Rufo, who has done more than any single individual to call attention to the rise of CRT-influenced corporate and government antiracist training programs and curricula at K-12 and higher education institutions, points to last fall's gubernatorial race in Virginia to make his case:

Terry McAuliffe, a popular former governor, went down to defeat after asserting that parents should not "be telling schools what they should teach." In the weeks following McAuliffe's comments, parents coalesced behind his opponent, Glenn Youngkin, who made educational choice the centerpiece of his campaign.

But what Rufo is actually describing is a political strategy, not a pedagogical program. Youngkin was not anyone's idea of a fierce proponent of school choice during the campaign, especially since his only concrete proposal to expand the amount and variety of educational offerings was a promise to "build at least 20" new charter schools, a meager offering according to choice activists who promote far more sweeping reforms such as "backpack funding" for students and the creation of Education Savings Accounts.

What Youngkin did emphasize was "keeping schools open safely five days a week," which had obvious appeal to parents strung out by COVID closures but can't be confused with school choice. He also campaigned against CRT, especially after McAuliffe's gaffe late in the campaign, but it remains far from clear exactly how big a role anything education-related played in Youngkin's win. Since taking office, Youngkin has tried unsuccessfully to fund charters, passed an executive order banning CRT, and established a tip line for "parents to send us any instances where they feel that their fundamental rights are being violated, where their children are not being respected, where there are inherently divisive practices in their schools."

Dictating what must be taught—and what absolutely cannot be taught—from a governor's mansion or a statehouse is a strange way to empower parents. It may be good politics, but if your interest is in reducing conflict over education and helping kids find places where they flourish, the state-level gag orders are a stumbling block to building coalitions to broaden and strengthen school choice, especially among low-income minority parents who strongly support school choice programs. The push on gag orders, Stewart tells me, "is a cancer on our movement. It's literally dividing school choice proponents from not having a big tent and moving forward with getting more constituencies involved in school choice."

Those concerns are echoed by other school-choice proponents. "I don't think the government should be making those decisions," says Corey DeAngelis, national director of research at the American Federation for Children. He believes that the Republican Party is by far the better party on choice because Democrats at every level are in the pocket of teachers unions, but he notes that many GOP members still want to control curriculum rather than letting parents choose. "Virginia public schools spend over $13,000 per student per year," he wrote shortly after Youngkin's win last fall, which he largely attributed to parental frustration. "At least some of that funding should follow the child to wherever they receive an education—whether it be a public, charter, private, or home school." (DeAngelis points to Pell Grants, student loans, and court decisions in various voucher cases to deflect constitutional questions about tax dollars going to religious institutions).

Under real school choice, no school at any level would be guaranteed tax dollars simply because it exists. Schools would live or die by their ability to attract and keep students based on their stated values and outcomes. "Parents should choose for their own kids," DeAngelis told me in a recent interview. "If a family wants to take their kid's education dollars to a school that has critical race theory [curriculum]…or a type of curriculum that aligns with their values, I think we should be OK with that. I think it's a problem when we start to force everybody into a system where they inherently disagree with what the curriculum is and how it's being taught."

State-level gag orders that ban specific texts and concepts are being sold as a way of minimizing conflict over K-12 curriculum but all they do is raise the stakes by moving the battle from the local school district to the state capital. The only real way to change this toxic dynamic is by giving parents and students real choice in education and letting a thousand curricula bloom. There will still be serious and important arguments over what should be taught and how, but, like religious differences today, they will be resolved peacefully and at the family level.

The post Want To Stop School Book Battles? Give Parents Real Choice in Education appeared first on Reason.com.