High-performance, affordable housing built in existing suburbs should be a big part of the solution to Australia’s housing crisis. Yet state governments and cities have struggled to achieve their goals of delivering affordable, multi-unit, infill housing.

For most people, their only choice is to buy an established home or off-the-plan. But there is a third way.

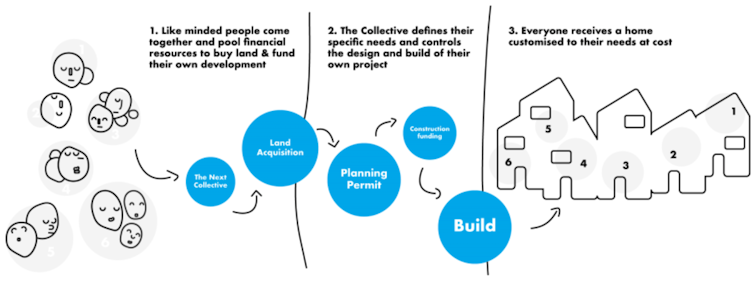

In 1990s Berlin, baugruppen (building groups) came to the fore in response to the German city’s housing crisis. Building groups are DIY collectives of future resident-owners who come together to develop their new homes. Households become producers rather than consumers, so they save on the developer’s profit margin and have more control over building design and quality.

At its peak, about 17% of new homes in Berlin were baugruppen projects. By 2017 more than 600 projects had been completed. The current master plan for redeveloping Berlin’s former Tegel airport calls for baugruppen to produce 2,000 homes – 40% of the project’s housing.

The success of baugruppen has inspired building groups in Australia. Data from one development and advisory service that assists building group members show members have on average saved around 10% on their new home building costs since 2010.

As well, they save on transfer taxes/stamp duties and mortgage interest payments. So in Victoria, for example, total savings could be as much as 16.5% on a A$1 million house.

Read more: Reinventing density: how baugruppen are pioneering the self-made city

Two home buyers compared

To illustrate the financial impact, let’s compare an example of two households. One household buys an apartment off the plan from a speculative developer. The other joins a building group.

Each household owns a home worth $840,000 at completion. The off-the-plan buyer pays $840,000, which includes the developer’s profit margin. The building group member gets their home for its cost price of $750,000. They effectively pocket $90,000 equity, which they have created.

In this example, the off-the-plan buyer puts down a deposit of around 20% (any less than this and they’d pay lenders mortgage insurance). The building group member must contribute the equivalent in equity plus an extra $70,000 or so over a four-year build (as construction financiers only provide only around 70% of the funds).

While this is a high hurdle for many, the building group member then only needs a mortgage with a loan-to-value ratio of 58% at settlement, which greatly reduces future interest costs. The ratio will be 77% for the off-the-plan buyer.

The rewards of the building group are significant, but members must also take on extra risk.

To start with, members have to contribute more upfront equity. They must also be able to inject cash during construction if there are unanticipated costs. They must accept a level of variability, too, in the final cost price of their home.

In contrast, off-the-plan buyers have the comfort of price certainty – albeit at the highest price a developer can squeeze from them. They have little control over the final build quality or timing.

The off-the-plan buyers will have equity equivalent to their deposit, but stamp duty and transfer fees reduce their overall wealth position. They are wholly reliant on future capital gains for their wealth to grow. The developer and government (through taxes) capture the initial equity created through the development process itself.

Read more: Affordable, sustainable, high-quality urban housing? It's not an impossible dream

Groups don’t have to do it all themselves

DIY does not mean the building group members must literally do everything themselves. New participants have emerged in the construction market that can provide development expertise to building groups.

In Australia, since 2010 Property Collectives has helped set up and manage ten building groups, building 80 homes worth around $97 million and saving members around $9 million. This has been achieved without any government subsidies or support.

Projects have ranged in size from four to 21 homes. They have been in well-located, inner and middle suburbs across Melbourne.

Property developer and consultancy Hip v Hype completed a three-home project using a similar approach in 2020.

Read more: Supersized cities: residents band together to push back against speculative development pressures

Scaling up this solution to boost supply

With the concept proven, the model is ready to be scaled up to deliver homes costing $600,000-$700,000 for middle-income and essential worker households. What is needed now is more institutional investment from impact investors (which seek social returns and often accept lower financial returns), community housing providers, member-based organisations (such as mutuals and co-operatives) and governments. They can use building groups to help create a new pathway to more affordable ownership and rental options.

Building groups also offer improved outcomes for shared equity schemes. Share equity involves the government or another investor covering some of the cost of buying the home in exchange for an equivalent share in the property.

Read more: Affordable home-ownership scheme offers a pathway out of social housing

Typically, shared equity schemes are reliant on variable capital gain in the future, which the owner-occupier uses to buy out the co-investor/owner. Developing housing (rather than buying existing housing) creates immediate equity (the difference between the construction cost and market value), which the owner-occupier can use to buy out the other party earlier.

If governments put equity into supplying new housing instead of (or in addition to) being a second mortgage holder on an existing home, this would create far greater financial benefit. Instead of adding to demand for housing it would add to supply, eliminating upward pressure on house prices from these schemes.

Tim Riley of Property Collectives contributed to this article. Andrea Sharam does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.