Censorship interrupts an oral history of a new book on the New Zealand Wars, longlisted for the Ockham awards

Dr Vincent O'Malley is the current go-to historian of the New Zealand Wars, as the author of a major history of the Waikato War and a general history of the Wars. His new volume, Voices from the New Zealand Wars, consists mostly of first-person narratives in which the conflicts of our past are told by many people who were there at the time. It's not the first book to tell these wars from first-person accounts - James Cowan's official history, published in the 1920s, remarkably prioritised oral testimonies from all sides - but this is a volume for our time and a welcome path into more historically-informed understandings of the past. O'Malley builds on and combines some of the strengths of his major predecessors, James I and James II, although he not surprisingly takes a more critical approach to Imperial and Crown actions than James Cowan's century-old account. He clearly approves of James Belich's provocative The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1986), which made the case for Māori military brain, not just brawn. A more detailed discussion of some periods - notably the East Coast Wars - emerges through the witnesses selected by O'Malley.

For those new to this history the book provides a very accessible introduction to the wars. O'Malley provides introductions to each war and incident, succinct but informative, and tells us enough about each informant so that we can place his or her perspective. There are accounts from different sides where they are available, but even where they are not, the selections are careful. I thought I might want to dip in and out rather than read right through, but in the end I couldn't look away, and found myself absorbed by the richness of these diverse accounts. What a variety of 19th century voices - from the articulate and persuasive, to semi-literate blow-by-blow accounts - would the next voice be a well-known figure, or an obscure bit-player? A wahine toa, a cleric, or a general?

One dimension of the Wars which emerges particularly strongly is the shifting tone and texture as events played out over time. In the War in the North in 1845, after the sack of Kororareka and yet another felling of the flagstaff on Maiki Hill, the Reverend Robert Burrows' account has something of the picnic about it, and the sense of ordinary amicable life going on around the scenes of conflict seems incongruous. The Māori at the Waimate Mission confide to Burrows that their relative Hone Heke may be angry when they do not go to support him. Later, Burrows confidently rides off alone towards Maiki Hill to see what was up and noted:: "On my way to the Bay this morning I met a party of Heke's men coming inland with plunder". They pause to give him a full account. Continuing on to the town, he chats with others who are busy sacking the settlement, and is offered a share of some lollies purloined from one of the ransacked businesses.

Similarly, George Clarke writes about Lieutenant Phillpotts, who was well-liked by both sides and whom the Māori called Toby: "Once at Ohaeawae, a little after dusk, Phillpotts crept up to the palisade, and began slashing with his cutlass at the flax screen, when, of course, nothing could have been easier than to strike him down, but instead of that an awful voice came from the ground at his feet, not five yards off: 'Go away Toby, go away Toby', and he went away." Phillpotts was later killed at Ohaeawai, which was no picnic. Cowan's official history, in recording his death, also noted the defenders' affection for him.

The late 1860s demonstrate no such across-the-lines goodwill and experiences related from both sides are horrific. Private John Henry Walker's involvement in the terrifying counter-attack at Te Ngutu o te Manu seems impossibly chaotic, a vivid nightmare he can't wake up from, as he lunges from one wounded or dead body to the next in futile and seemingly endless efforts to retrieve them. He enlists others to help but they are picked off by the defenders in their hidden positions; the toll mounts relentlessly. He witnesses the killing of two children. Then comes his miserable journey, wounded and in the pitch darkness, back along to Camp Waihi, as he gradually meets up with the bedraggled trail of other injured men finding their way back to safety. The next account, given as court testimony by Ihaka Takarangi, relates the infamous Handley's Woolshed incident, in which troopers attacked children who had ventured away from the nearby Nukumaru pā. One of those children, Takarangi was wounded but survived; two of his friends did not.

From the many perspectives and testimonies we gain an intimate sense of what people thought worth commenting on. There is the mundane - the frequent difficulty of getting decent food (Frederick Gascoyne treasures the gift of a delicious chunk of boiled horse, or the troops' response when George Grey accepted military advice from Tamati Waka Nene (the Ngāpuhi chief allied with the British): it was "the talk of the camp". And the consequential: the terrible shock of defeat at Puketekauere for the young William Marjouram; or Lieutenant-Colonel Carey's considered assessment of the British victory at Māhoetahi.

There has never been much doubt about what happened once the whare at Rangiaowhia was alight and an old man came out with his arms raised: some of the fired-up troops shot and he was killed

The past rubs up against the present throughout, in some cases more obviously than others. Henry Halse was tasked with taking Grey's famous ultimatum - demanding that Māori living south of Auckland swear loyalty to the Crown or move south into the Waikato - to Mangere, Ihumatao and Pukaki in July 1863, as Grey quietly prepared for the invasion of the Waikato. Halse's report to the Native Minister details the reactions of the various groups of Waikato Māori who were living in this area at the time, as they tried to make sense of what Grey intended, and as they came to their decisions about whether to stay or leave their livelihoods and go. Halse's fascinating on-the-spot record leaps into contemporary relevance in the wake of recent events at Ihumatao.

If we needed any reminder of the rapid Māori adoption and strategic use of literacy in the 19th century, there are plenty here. Documents include Renata Kawepo's stinging rebuke to Hawke's Bay provincial superintendent Thomas Fitzgerald, calling him out for altering his speech given at Kohimarama before sending it for publication. Drawing on the skills of both oral and literate cultures, Kawepo lists the discrepancies between Fitzgerald's spoken and written versions and goes on to eviscerate government duplicity in its proceedings especially with regard to land. A similar condemnation appears in the compelling 1867 petition of the self-described 'Government Natives' to the Crown, asking for remediation after the Native Land Court sat in Tūranga and demanded the ceding of their best land, although they had not fought against the Crown. Captain Biggs who had harassed them to give up their land wanted "to get all the level country, and we might perch ourselves on the mountains".

The rich account given by Honana Te Maioha of the formation of the Kingitanga makes for wonderful reading. It includes - among much else - the metaphorical language of the debate over the selection of a king: "Rotorua is a place of ponds, meaning that the sun would soon cause them to evaporate ... Taupo is a shallow sea, meaning that the people were not many, and more scattered ... Waikato is a giant river. The meaning of all this was that the king should be selected from Waikato." And years after the events, Maraea Morete recalled the terrifying nights and days of Te Kooti's attack on Matawhero on November 9-10, 1868.

As he has done in his history of the Waikato War, O'Malley gives particular attention to Rangiaowhia, which had long been much more vivid in Tainui than in Pākehā memory, where Ōrākau was the emblematic battle. Here these two events are given equivalent weight. O'Malley addresses the key issues relating to Rangiaowhia, first that it was attacked despite being 'off limits' (it was occupied by women, children and old men, who had been sent there for safety, and the British military knew this), and second whether troops had deliberately or accidentally set fire to a whare occupied by a number of people. There has never been much doubt about what happened once the whare was alight and the first of its defenders, an old man, came out with his arms raised: despite shouted commands from officers to hold fire, some of the fired-up troops shot and the old man was killed, which meant that no-one else in the burning whare emerged to surrender. Still at issue is whether the whare was a 'whare karakia', if not formally a church, as the last account, of a woman who fled the village before the attack, suggests. These accounts do not resolve the questions that still hang around Rangiaowhia, but O'Malley re-centres Rangiaowhia, which despite Cowan's fairly detailed account had been given little attention in the Pakeha world for decades.

O'Malley also reassesses the significance of Orakau, shifting it away from the older, safe-for-Pākehā narrative of 'mutual respect' towards the bloody siege it clearly was. He wisely doesn't attempt the comprehensive account of the battle given by Cowan (which includes many first person narratives from both sides) but gives two of the most important narratives in full: that of the Ngāti Maniapoto rangatira Te Winitana Tupotahi, and second, the testimony given to parliament in 1888 by the Ngāti Te Koheroa chief Hitiri Te Paerata, whose father and brother died in the battle, and whose sister Ahumai became famous for her refusal of the government offer to allow the women and children to leave the beseiged pā. (Along with Paterson and Wanhalla's anthology of Māori women's voices, this collection puts wahine Māori participation back into a history in which they have often been more or less invisible.) Two pieces relating to the aftermath of the war in the Waikato, by Aterea Puna and Henry Sewell, both centre on the government's not-so-subtle land-taking agenda. Sewell rails against the 19th-century fake news perpetrated by George Grey when he invented a 'plot to attack the settlers' to justify the invasion of Waikato. For a precursor to Facebook's capacity to assign false quotations, take words out of context, and manipulate communications, students of political sculduggery will find here, as Sewell comments, 'a sample of the way men's minds are inflamed'.

O'Malley renders it as "n–––––r". To censor the word overloads it with the historical and contemporary freight it carries for 21st century America

There are two wonderful defenders' accounts of Pukehinahina (Gate Pa), one by Hori Ngatai, the other by Heni Te Kiri Karamu; and a third from the attacking side by Ensign Spencer Nicholl. All are well-known - the Belich documentary series quoted from all three and Cowan quotes at length from Heni Te Kiri Karamu's letters - but it is very informative to have all three accounts given in full. But not quite in full, and here I take issue with O'Malley: in Nicholl's account the word "nigger", which Nicholl used freely, is rendered as as "n–––––r". Offensive as the word now is to most of O'Malley's readers, that is surely the point: colonial soldiers did use it, and it tells us something about them and their time. Moreover, to censor the word as is done here overloads it with the historical and contemporary freight it carries for 21st century America, obscuring its more restricted derogatory meaning in19th-century New Zealand.

Colonial soldiers were not all of one mind. The contrast between Nicholl and Morgan S. Grace is illustrative - Grace was an Irishman who saw only too clearly the parallels between colonial experience in Ireland and New Zealand. Day to day accounts point up the contrasts between how different commanders affected the troops and the conduct of the war - the tone of the war in Taranaki and Whanganui under the disillusioned and soon-to-resign General Duncan Cameron and his successor General Trevor Chute is vividly illustrated by the writing of the soldiers who served them. And Chute's suspicion and disregard for Māori allies is a contrast to the generally unloved Whitmore's respect for 'the friendly Natives' and his willing admission in an early East Coast attack that he had underestimated their fighting capacity.

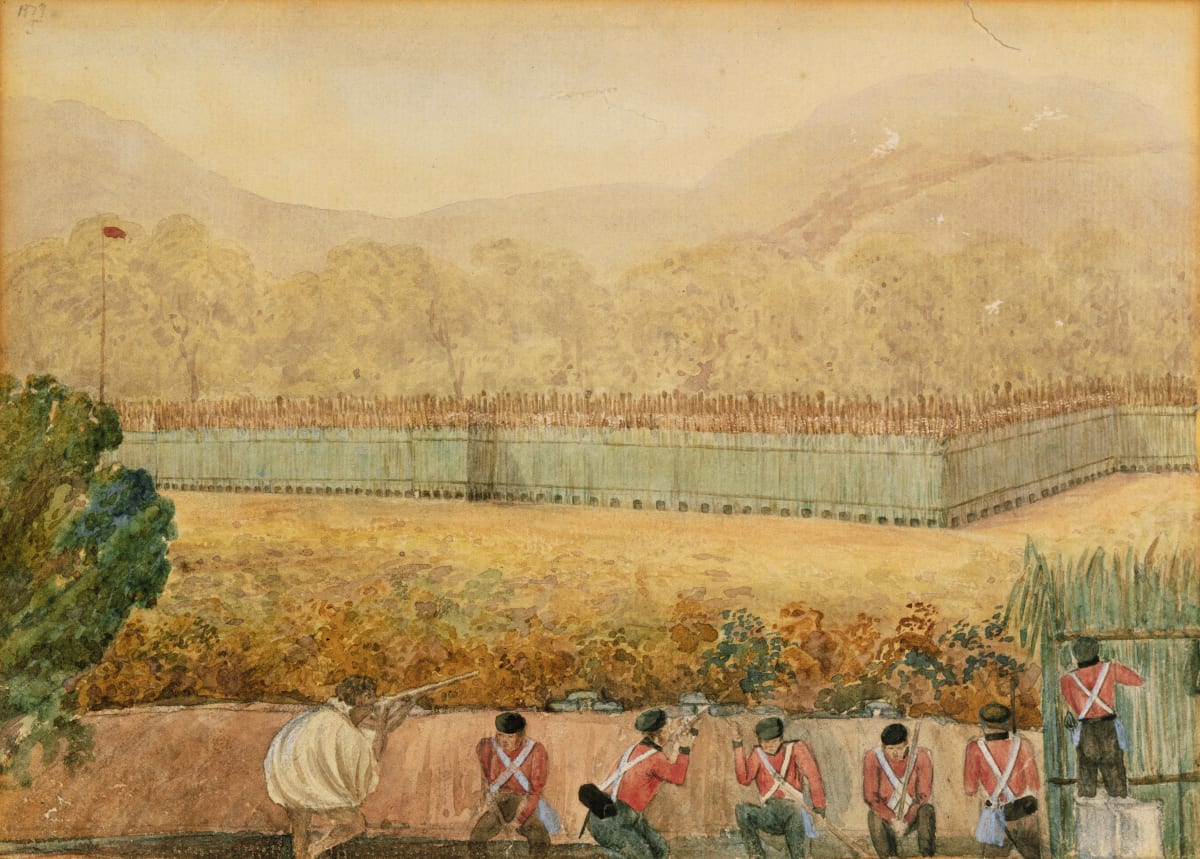

Plentiful and handsomely-produced images vastly enrich the text. They include many landscapes and battlefield sketches, and many of the Lindauer portraits of Māori leaders. It is especially pleasing to have such a superb reproduction of the beautiful portrait of Wiremu Tamehana Tarapipipi, conveying the calm but also the world-weariness of an embattled would-be peacemaker. (I was surprised not to find in the text, incidentally, an example of Tamehana's letters.) With the many studio shots of soldiers, often in their retirement, there are some standout photographs such as that of Maraea Morete splendid in Salvation Army uniform, and a number of present-day images (of disgraced statues, as well as shots of pā sites as they are today). Bridget Williams Books' high production standard is evident once again.

What can such a book offer to a new generation, particularly as New Zealand history makes its way into the core school curriculum? There has already been some contention about how that history should be taught. The book's introduction begins with a disclaimer - "A retweet does not constitute endorsement" - indicating that the volume includes many points of view with which O'Malley does not agree. This self-defensive opener is a stark reminder of the difficulties of dealing fairly with the past in the present hypervigilant moment. Historical thinking is a scarce commodity these days. A serious investigation of the mindsets of people in the colonial period is vulnerable to the slings and arrows of instant experts firing from high moral ground, and even the well-respected O'Malley is clearly aware of the threat. This book provides some corrective to quick and easy judgment. It is populated with real human beings, who arrive with inherited beliefs. We watch as they grapple with circumstances seldom of their own making. They do not know what will happen in the weeks and months ahead, let alone over a century and more. I like to think that teachers will make frequent use of extracts from the book as the new history curriculum rolls out: am I too optimistic in thinking that these diverse voices may help to foster better-informed, more nuanced historical thinking in the coming generation?

Voices from the New Zealand Wars/He Reo Nō Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa by Vincent O'Malley (Bridget Williams Books,$45) is available in bookstores nationwide, and has been longlisted for the best book of non-fiction at the 2022 Ockham New Zealand national book awards.