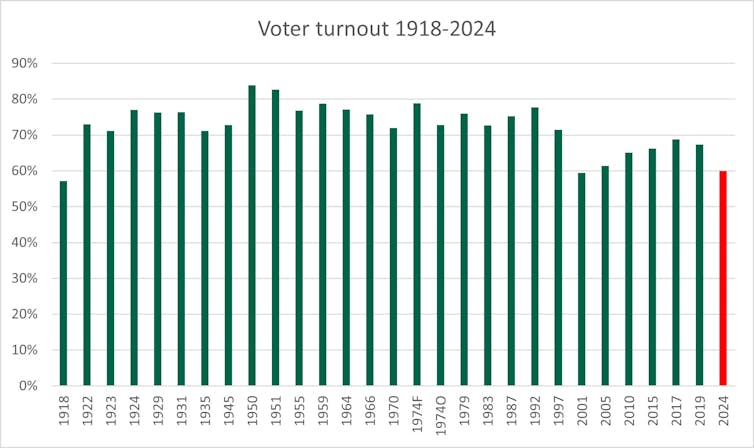

Labour won the 2024 election by a landslide. But a significant story from the night’s results was the low turnout across the nation – the lowest since 2001. At 59.9%, voter turnout was significantly lower than the 67.3% turnout in 2019.

Prime minister Keir Starmer’s own constituency recorded a drop from 56,786 votes cast to just 38,602. The votes received by Starmer himself halved, from 36,641 in 2019 to 18,884. In Manchester Rusholme, a seat held by Labour, turnout was just 40%.

And these figures overestimate turnout. They follow the British tradition of calculating turnout as a proportion of registered voters. There are millions of unregistered voters who are not even counted.

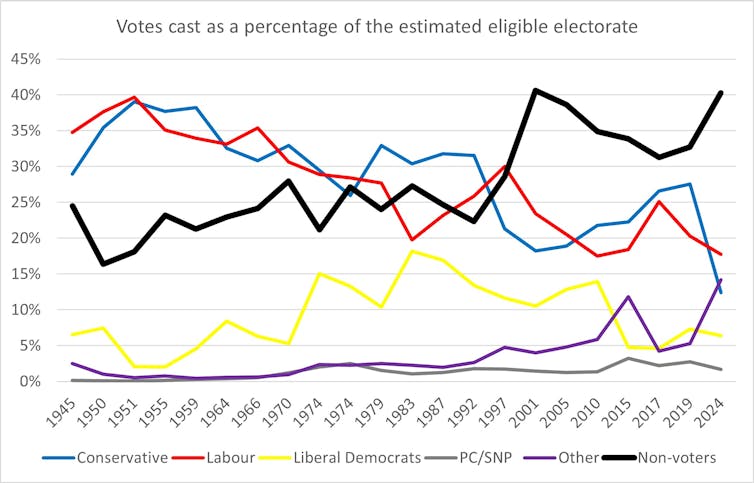

Another way of looking at turnout is to calculate it as a proportion of those who are eligible. This is a better calculation of participation because it includes everyone who is eligible to participate.

This data shows that in the UK, there has been a long-term decline in support for the main two parties since 1945. This runs alongside a growth in the proportion of people who do not vote at all. There was a landslide, but the landslide was for non-voters.

Turning away

We won’t know immediately why turnout in 2024 was so low. One explanation is that the result was long portrayed as a foregone conclusion. For weeks, opinion polls showed a clear lead for Labour, and Conservative tactics turned to calling for the electorate to limit a Labour “supermajority”.

Turnout tends to be higher when elections results are expected to be close. Talk of a Labour landslide may have therefore led some people to feel less compelled to vote.

Disillusionment with parties and politics will be a second explanation. The COVID inquiry exposed a culture of rule-breaking in parliament, which many voters may have found offputting about politicians in general. Voters may also have become disappointed with politicians’ ability to address pressing issues such as the cost of living crisis and long wait times for NHS appointments. It is therefore little surprise that citizens may have lost confidence in candidates and parties.

Electoral reform

A third explanation is that this is the first general election in which photographic voter identification has been compulsory. Research has suggested that this might affect turnout. Mitigating mechanisms might be needed, which could include extending the range of types of identification required.

Alternatively, the best option might be to simply scrap a requirement that seems to use a sledgehammer to crack a nut. My research with Alistair Clark of Newcastle University shows that voter fraud – someone casting a vote for someone else – is extremely rare.

The short electoral timeframe may have also meant that overseas voters struggled to return a postal ballot in time.

Now the election is over, political parties will need to take a careful look at how to re-engage voters for the future. This might involve reviewing electoral laws. Automatic voter registration could make a considerable difference, for example.

There will also need to be introspection by political parties on the methods they use to campaign and engage with the public. They will need to find ways to inspire the electorate to vote for them.

Toby James has previously received funding from the AHRC, ESRC, Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, British Academy, Leverhulme Trust, Electoral Commission, Nuffield Foundation, the McDougall Trust and Unlock Democracy. His current research is funded by the Canadian SSHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.