On first listen, hearing a disembodied, low-bitrate Johnny Cash perform Aqua’s 1997 Eurodance hit Barbie Girl is a pretty good laugh.

The sound of Cash’s grizzled, stately voice singing the words “you can brush my hair, undress me everywhere” makes for an undeniably funny contrast; much like hearing Eric Cartman take on Evanescence’s Bring Me To Life, or Donald Trump and Joe Biden team up for Sultans of Swing.

There’s a reason why teens in their thousands have been creating and sharing these so-called AI cover songs over the past year; at first glance, it’s high-grade silliness. Using AI-powered software, fans can transform any song’s vocal into a 'deepfake' version of another singer’s voice through a process called AI voice cloning.

Popular music is on the brink of a radical transformation, one in which AI compels us to reconsider the very notion of what a singing voice represents

Voice cloning lets them mix and match any voice with any song, no matter how preposterous the combination. Real people’s voices, unique timbres once tied inextricably to a person’s identity, become mere tools, new colours with which to paint over the canvas of popular music in any which way we please. “Life in plastic, it’s fantastic”, the song goes. “Imagination, life is your creation”.

As we continue listening, though, it's hard not to feel a twinge of unease. The tech is advanced enough that the ‘cover’ sounds almost exactly like Cash; the creator has even supplied a convincingly bluesy backing track. But something doesn’t sit right, and it’s more than just the uncanny valley.

The joke quickly gets old, and we're left considering the implications of the fact that anyone’s voice can now be lifted from their music and used in anyone else’s, freely, easily and without permission. It soon becomes apparent that popular music is on the brink of a radical transformation, one in which AI compels us to reconsider the very notion of what a singing voice represents.

Every day, thousands are training AI models on the work of well-known artists and using these models to mimic their voices

Every day, thousands are training AI voice models on the work of well-known artists and using these models to mimic their voices, whether that’s by remixing existing music or transforming their own. All it takes to train a model is to strip the vocals from a handful of an artist’s songs using stem separation services, then run them through free and open-source AI voice cloning software.

It’s not a simple process, but as the technology develops, it’s only going to become more accessible. Though the majority of homemade AI cover songs aren’t monetized by their creators - just uploaded on TikTok and YouTube for fun - some have taken things a step further.

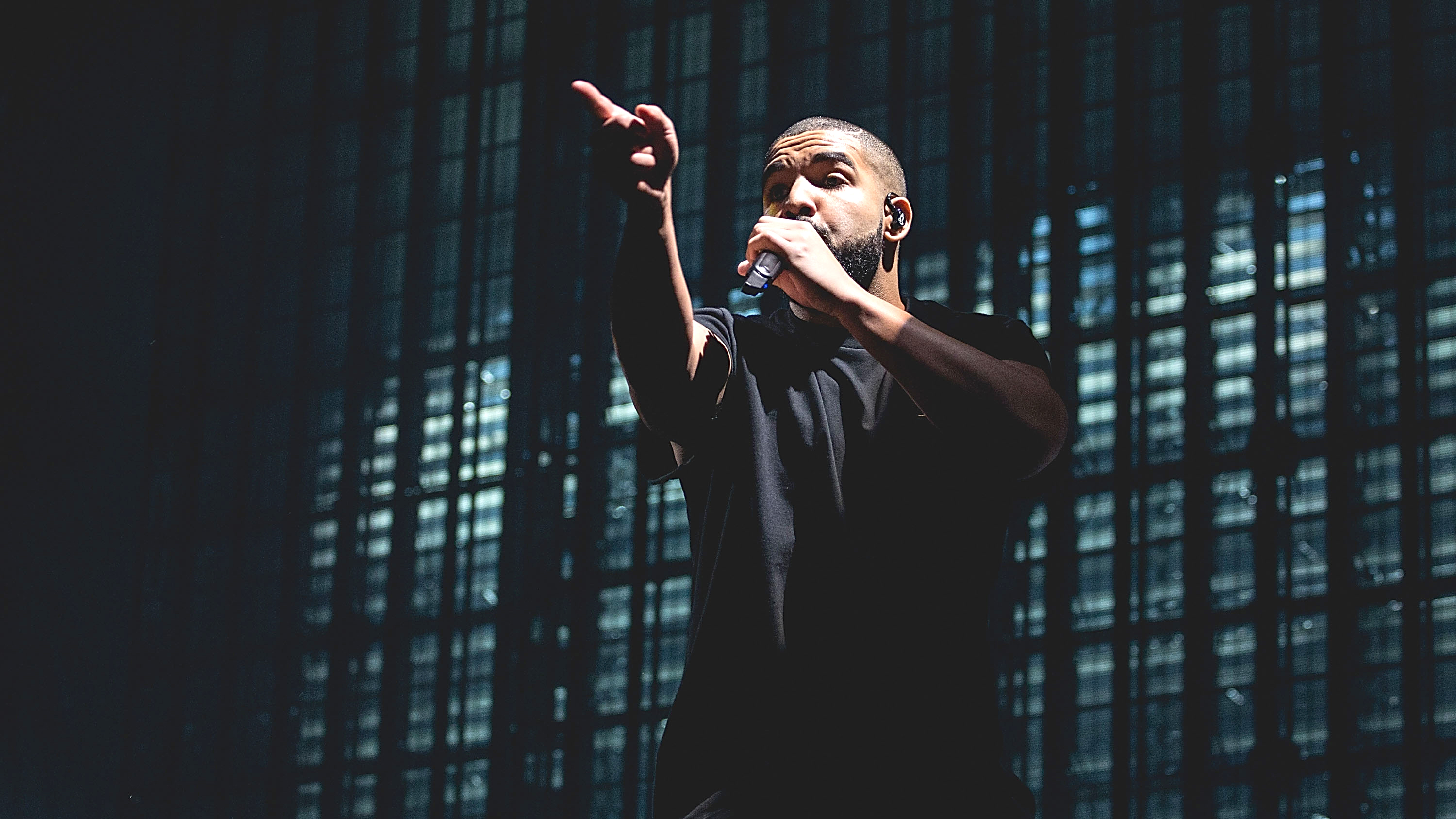

Earlier this year, an anonymous producer called ghostwriter977 cloned the voices of Drake and The Weeknd on a track called Heart on My Sleeve before uploading the song to streaming services. The song went viral, racking up hundreds of thousands of streams and millions of views on TikTok before disappearing as quickly as it arrived.

Billboard estimates that the track may have brought in close to $10,000 for its creators before being removed, but it’s not known whether these royalties were paid out. Heart on My Sleeve’s video was also taken down from YouTube, reportedly due to a claim from UMG, Drake and The Weeknd’s label and the world’s largest music company. The song has since reappeared on YouTube, hosted across a number of different channels.

In a statement given to Music Business Worldwide, UMG did not confirm whether it was behind the song’s takedown, but was clear in its condemnation of the broader practice of AI voice cloning, describing it as “a breach of our agreements and a violation of copyright law”.

The unprecedented situation that the industry now finds itself in, UMG claims, “begs the question as to which side of history all stakeholders in the music ecosystem want to be on: the side of artists, fans and human creative expression, or on the side of deep fakes, fraud and denying artists their due compensation.”

The training of generative AI using our artists’ music [...] begs the question as to which side of history all stakeholders in the music ecosystem want to be on

Universal Media Group

In the months since Heart on My Sleeve's release, major industry players have doubled down on their efforts to stamp out unauthorized voice cloning. In June, The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) issued a DMCA subpoena to chatroom platform Discord, asking them to reveal the identities of individuals using the Discord server AI Hub, who they claim have shared datasets of copyrighted songs for use in training AI voice models.

Despite the RIAA's demands, Discord have yet to shut AI Hub down. The server is home to an online community for those experimenting with voice cloning. Until recently, AI Hub hosted a bot that enabled its users to quickly and easily access voice models of artists such as Drake, Kanye West and Justin Bieber by uploading vocals to be processed automatically. In July, that bot was taken down.

One of the server's moderators, who goes by the username Mosh, claims that they shut the bot down because UMG threatened them with legal action, accusing them of "profiting from the likeness" of Juice WRLD, a now-deceased rapper whose voice model was available to be used through the AI Hub bot. Mosh says that the case was later dropped after they made clear that they weren't making any money from voice cloning, just experimenting with it for fun.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the major labels view AI voice cloning as an existential threat

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the major labels view unauthorized voice cloning as an existential threat. Much like when digital piracy threatened to upend the music industry in the ‘00s, the rise of an easily accessible new technology is enabling anyone with a computer and an internet connection to take something that belongs to the labels and the artists they represent. But where Napster allowed its users to illegally download copyrighted music, voice cloning lets people appropriate something that, arguably, isn't protected directly by copyright: the sound of an artist’s voice.

As is often the case when new technologies appear, our legal systems aren't well-prepared to deal with the misuse of voice cloning. Copyright law deals with copyrighted works; songs, lyrics and melodies that can be identified and protected. Musically, a voice is a timbre, and musicians share timbres all the time.

Instruments are used across thousands of different songs, and you wouldn’t sue somebody for imitating your guitar tone. While AI voice cloning software is trained using copyrighted material (the ethics and legality of which is a separate, and no less knotty, issue) its output only lifts the vocal timbre from that material, not the copyright-protected melodies or lyrics.

More than just a timbre, though, a voice forms part of a singer's identity, and it’s on that basis that the law can protect those whose voices are being cloned without permission. Most countries recognise a person’s right of publicity; the right to control the commercial use of certain aspects of their identity, such as their name, image and likeness. In the US, this isn’t enshrined in federal law, but instead through a patchwork of state legislation and common law. But there’s legal precedent to suggest the unauthorized mimicry of a voice can be challenged successfully in the courts by asserting these rights.

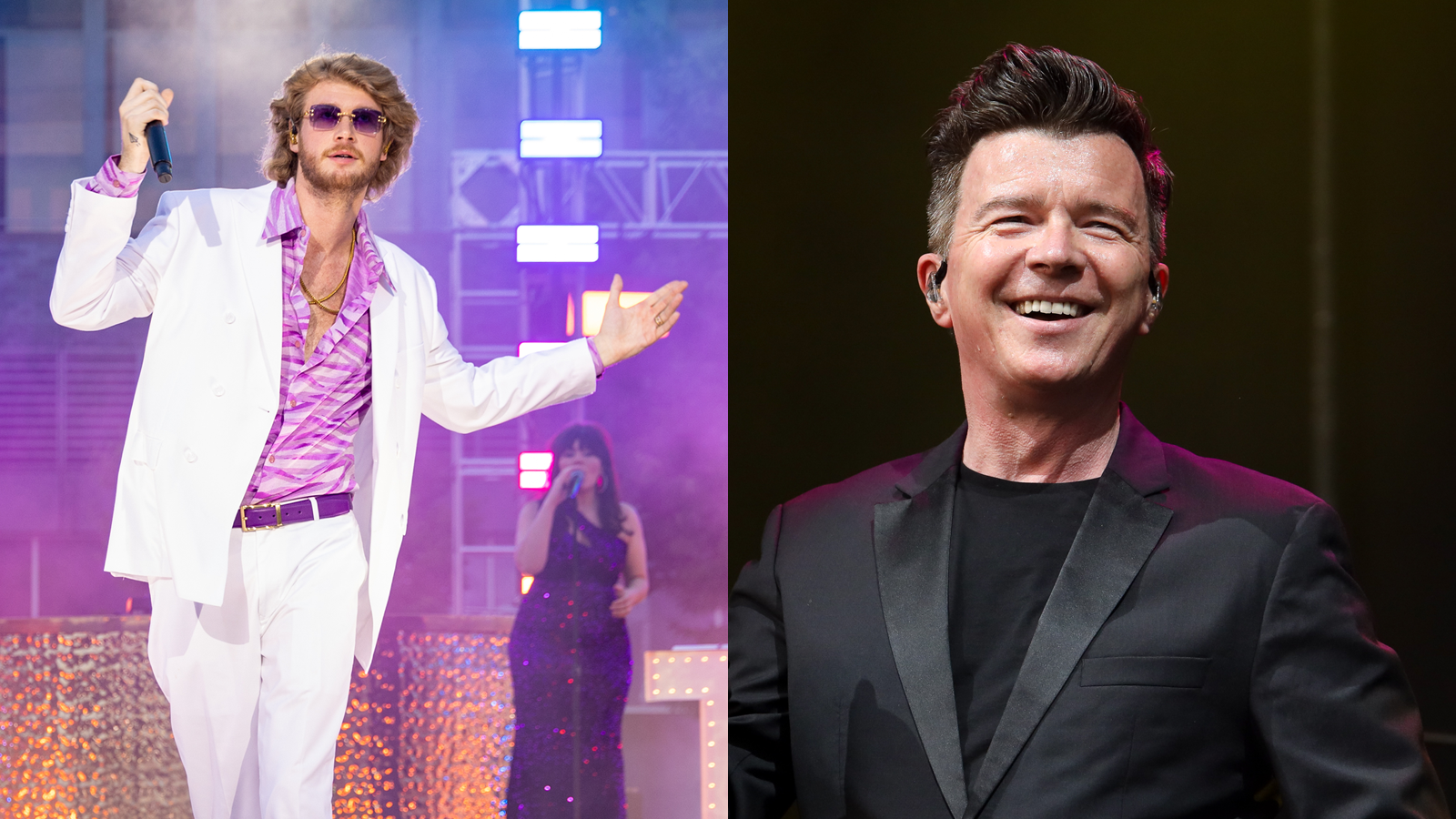

Rick Astley hires Blurred Lines lawyer to sue rap artist over vocal impersonation

In 1988, Ford tried to hire actress Bette Midler to voice a commercial, but she declined. Instead, they hired one of her backing singers and asked her to impersonate Midler’s vocal delivery on a song of Midler’s they’d obtained a license to use. Midler then sued Ford, claiming that her voice was protected as a property right; while an initial hearing found that there was no legal principle protecting the use of her voice, on appeal, the court ultimately ruled that under California law, a famous individual’s voice is essential to their personal identity, and that it’s unlawful to imitate it without their consent.

The US courts doubled down on this four years later when Tom Waits sued Frito-Lay for using an impersonation of his voice in a commercial. Confirming that “when voice is a sufficient indicia of a celebrity’s identity, the right of publicity protects against its imitation for commercial purposes without the celebrity’s consent”, the judge clarified that in order for a voice to be misappropriated, it must be distinctive, widely known and deliberately imitated for commercial gain. These judgements could seemingly protect big names from voice cloning, but what about smaller, independent artists who would struggle to argue that they’re “widely known”?

The majority of AI voice cloning currently taking place is happening below the radar; tech-savvy fans making use of open-source software at home and experimenting by making AI covers to show their friends. But as the technology becomes more accessible, the industry will be forced to adapt to the fact that anyone will be able to clone the voices of world-famous artists in their music.

As was the case with music piracy in the ‘00s, only so much can be achieved by chasing down individual offenders and threatening legal action. The solution, in the end, will be to offer a legal alternative that can be monetized by labels and artists. The industry’s answer to piracy was music streaming; its answer to voice cloning is likely to be something equally revolutionary.

The industry’s answer to piracy was music streaming; their answer to voice cloning is likely to be something equally revolutionary

Last week, it was revealed that UMG and Google were in talks over licensing the voices of artists in UMG’s catalogue for use in AI-generated music. While talks are still in their early stages, it appears that the goal is to develop a paid-for tool that anyone can use to clone the voice of artists from UMG’s catalogue. Artists will be given the choice to opt in to the platform and earn royalties from the licensed usage of their voice. The world’s biggest record label, Universal Media Group is home to artists like Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Harry Styles and Kendrick Lamar.

In a statement shared today to the Google-owned YouTube's blog, UMG CEO Lucian Grainge outlined a plan for their "artist-centric approach to AI innovation". "Today's rapid technological advancements have enabled digital manipulation, appropriation and misattribution of an artist’s name, image, likeness, voice and style", Grainge says, "the very characteristics that differentiate them as performers with unique vision and expression."

In the face of these challenges, UMG plans to "establish effective tools, incentives and rewards – as well as rules of the road – that enable us to limit AI’s potential downside while promoting its promising upside". The first step in UMG's collaborative venture with Google is the launch of the Music AI Incubator, a working group of UMG artists, songwriters and producers tasked with providing feedback to Google on the development of its AI-powered musical tools.

Warner Music, another of the 'big three' major labels, has also reportedly been discussing a partnership with Google on AI. In a statement to investors, Warner’s Chief Executive Robert Kyncl said that "with the right framework in place", AI voice cloning could "enable fans to pay their heroes the ultimate compliment through a new level of user-driven content [...] including new cover versions and mash-ups". Once these tools are developed, an artist’s voice could become a new form of merchandise; singing in their voice will become another way for fans to connect with their favourite stars.

Though it seems likely that they will attempt to monetize the AI cover songs trend through their own platform, it’s not clear yet how much further the major labels will take their venture into voice cloning. In recent months, a handful of fledgling services have popped up offering music-makers the opportunity to legitimately clone the voices of artists on their roster; these give us a glimpse of the direction the majors might take. myvox, launched earlier this month, allows artists to license their AI voice model to users of the subscription-based platform and receive a share of royalties from any tracks released that use it.

myvox’s first ‘AI artist’ is named Dahlia, and its voice is based on a voice model created using the singer, songwriter and producer Sevdaliza's voice. Myvox users can transform their vocals into Dahlia’s, distribute those tracks on streaming services through myvox, and 50% of the royalties will go into Sevdaliza’s pocket. According to myvox’s founders, this not only gives Sevdaliza’s fans the opportunity to collaborate with her, but also helps aspiring music-makers get noticed by using the vocals of a well-known artist in their music.

Myvox not only benefits its users, the founders tell us, but also opens up new opportunities for artists. “We’re creating a new revenue stream and passive income for artists,” says myvox founder Arianna Broderick. “They’re able to participate in the benefits while retaining control.” Previously, anyone in need of vocals for their music might typically hire a session vocalist and shell out for studio time. Platforms like myvox offer a cheaper, easier alternative; one where the featured vocalist doesn’t have to sing a single note, let alone turn up to the studio.

Moises.ai is another platform that’s recently begun offering voice cloning alongside a suite of other AI-powered tools. “We’re seeing professional producers use vocal models of different singers to test and demo new tracks,” Moises.ai founder Geraldo Ramos tells us. “Not all musicians have access to talented vocalists or have the means to invest in their performances during the creative process. We see artists using this as a tool to expand their creative reach and try different approaches, the way you might score a melody for a different instrument.”

Currently, voice cloning platforms like these are browser-based; you log in, upload a vocal recording and download the processed version. This might be an impractical workflow for those producing on a professional level, but both Moises.ai and myvox are developing VST plugins that bring voice cloning technology into the DAW. Soon, it’ll be possible to record some scratch vocals in your own voice, open up a plugin and browse a library of potential voices to clone. “We see myvox as another part of people’s vocal chain, just like pitch correction, compression, or reverb”, says myvox’s Arianna Broderick.

“We see myvox as another part of people’s vocal chain, just like pitch correction, compression, or reverb”

myvox founder Arianna Broderick

Rather than partnering with services like myvox, some artists are taking things into their own hands. Earlier this year, Grimes launched Elf.Tech, an open-source software tool which can be used to clone her voice, proclaiming: “Grimes is now open source and self-replicating.” Anyone can release the music they’ve created using the software, but Grimes has asked that she receive 50% of any royalties. Elf.Tech has already been used by thousands of artists; Australian DJ and producer recently released Cold Touch, an official collaboration with Grimes’ voice model (credited as GrimesAI) through Diplo’s Mad Decent label.

Musician, producer and academic Holly Herndon has been miles ahead of the game on voice cloning for several years. In 2021, Herndon unveiled Holly+, the first AI voice model ever made available to the public by an artist. In order to “decentralize access, decision-making and profits” made from Holly+, Herndon set up a DAO (Decentralised Autonomous Organization) co-operative that owns the IP and votes to approve its usage. Any funds generated from the use of her voice model will be redirected to the DAO to be shared amongst the artists using it and support further development.

"A balance needs to be found between protecting artists and encouraging people to experiment with a new and exciting technology"

Holly Herndon

“Vocal deepfakes are here to stay,” reads a statement on Herndon’s website. “A balance needs to be found between protecting artists and encouraging people to experiment with a new and exciting technology. That is why we are running this experiment in communal voice ownership. The voice is inherently communal, learned through mimesis and language, and interpreted through individuals. In stepping in front of a complicated issue, we think we have found a way to allow people to perform through my voice, reduce confusion by establishing official approval, and invite everyone to benefit from the proceeds generated from its use.”

While Herndon’s vision of an equitable future for voice cloning is admirable, it’s doubtful that the major labels will adopt such a community-minded approach. Where exactly their adoption of the technology could lead isn't clear, but it’s entirely possible that in a few years, it could become common practice for artists to license the use of their voice model on a grand scale.

Turn on the radio, and you won’t know if you’re hearing Taylor Swift or officially licensed AI Taylor Swift; is that really a guest verse from Jay-Z, or is it just his voice model? You may even be able to boot up your DAW, record a vocal, open up a plugin and scroll through a list of famous artists (living and dead) before deciding who’ll ‘feature’ on your next track.

In a world where anyone can duplicate Taylor Swift’s voice, is that voice - one of the defining features of her artistry - devalued?

Like many recent developments in artificial intelligence, voice cloning threatens to create as many problems as it solves. If its usage becomes widespread in popular music, will the charts become oversaturated with cloned voices? How will listeners tell the difference? And with 120,000 new tracks uploaded to streaming services each day, how will we identify and remove songs that feature unlicensed voice clones? Platforms like Moises.ai claim to have developed technology that enables artists and labels to detect tracks that use their voice model without permission, but it remains to be seen whether this functions effectively in practice on a broader scale.

Moreover, the issues raised by voice cloning are not only practical but ethical. In a world where anyone can duplicate Taylor Swift’s voice, is that voice - one of the defining features of her artistry - devalued? For professional vocalists and songwriters, the singing voice is not only an essential element of their personal and artistic identity, it’s the tool through which they make their living. Until now, voices have belonged inalienably to their owners; they could be impersonated but not stolen outright. But by digitizing, decontextualizing and commodifying the voice, voice cloning strips it away from its owner and transforms it into a tool like any other - a tool that can be misused.

We already see artists signing away the rights to their master recordings early on in their career, eager to get a foot in the door; it’s easy to imagine aspiring vocalists signing away the ownership of their cloned voices to labels for the same reason. If UMG and Warner are developing voice cloning tools for their artists, it begs the question of whether they believe that artists’ voices belong, at least in part, to record labels, and if the money generated by those artists’ voice clones will be shared out equitably.

By decontextualizing and commodifying the voice, voice cloning strips it away from its owner and transforms it into a tool that can be misused

Though questions like these are necessary, it’s worth remembering that voice cloning differs significantly from purely generative AI in the sense that it’s not creating something from nothing. Instead, it’s transforming something that’s already there. In its current form, at least, the technology requires an existing vocal recording on which to graft its cloned voice. As long as the owners of both voices are compensated, voice cloning won’t be putting vocalists out of a job - in fact, it might be making their job easier.

Earlier this year, Ice Cube was accused of hypocrisy when he described AI as “demonic”; as a hip-hop forefather, his success was partly built on the use of sampling, another innovative and revolutionary technology that empowered us to transform musical material made by others into something new. Sound familiar?

Sampling provoked its fair share of scepticism in its early days and more than a few have fallen foul of its misuse in the years since, their work sampled without recognition or compensation. Ultimately, though, the industry adapted to accommodate the new possibilities that the technology created, and sampling became a powerful tool that shaped the sound of modern music for the better. As we prepare for voice cloning to disrupt the music industry, let’s hope that its story has a similar ending.