Vincent Namatjira, a Western Arrernte artist, is Albert Namatjira’s great-grandson. His genre is portraiture, but with a twist: loaded with satire and post-colonial politics.

He was the first Aboriginal artist to win the Archibald prize in 2020 with a portrait of fellow Indigenous man, footballer Adam Goodes.

His double-sided portrait on plywood, Close contact, won the Ramsay Prize in 2019. In this freestanding portrait Namatjira employs his strategy of inverting history: the artist commands the viewpoint, facing outward; Captain Cook on the rear side trails behind. Close Contact is the entry portrait for this fabulous survey exhibition, Vincent Namatjira: Australia in Colour on show at the Art Gallery of South Australia.

The paintings on display echo Namatjira’s mantra that his paintbrush is his weapon and that art has the power to change the world.

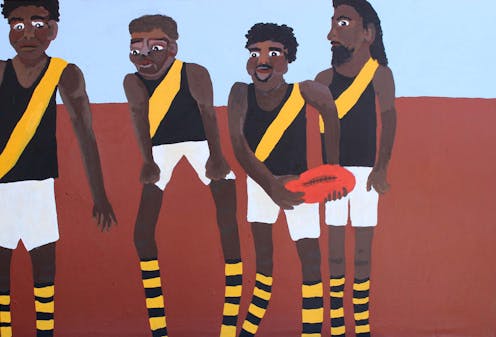

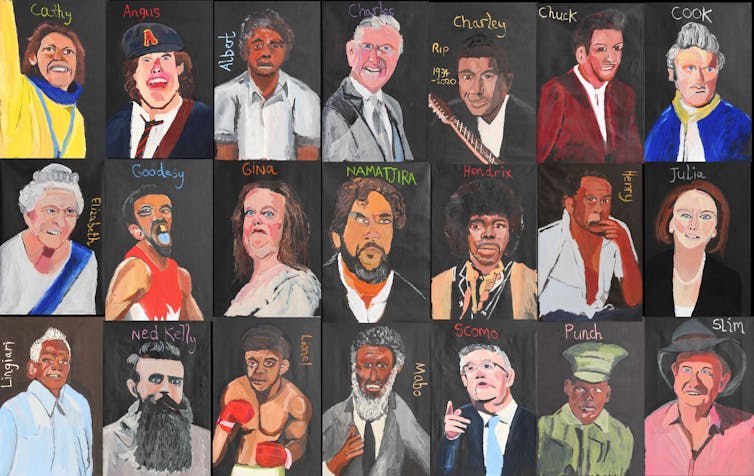

His multi-panel set of portraits, Australia in Colour, showing a mix of the rich and powerful such as Gina (Rinehart) and Scomo side-by-side with local heroes such as musician Angus (Young) and Ned Kelly along with Aboriginal heroes, Cathy (Freeman) and Vincent (Lingiari) sets the tone for the exhibition.

Nothing is off limits.

Read more: Terra nullius interruptus: Captain James Cook and absent presence in First Nations art

Artistic lineage

Vincent Namatjira is very conscious of his lineage, and his role via portraiture in continuing what Albert Namatjira started in landscape in portraying Country.

This is underscored in his twin portrait, Albert and Vincent (2014), showing himself in the same pose William Dargie employed in his Archibald prize-winning portrait of his great-grandfather in 1956.

But for Vincent Namatjira, there is a timely assertiveness in addressing wrongful behaviour as in his telling portrait of Adam Goodes.

Read more: At last, the arts Revolution — Archibald winners flag the end of white male dominance

That assertiveness extends to correcting the historical record in his series of Unknown soldiers (2020) which portrays First Nations men who served in the first world war. Many chose not to declare their Aboriginal heritage so they could enlist. The paintings completed on army surplus camouflage fabric reinforce that their stories are still hidden, waiting to be woven into an inclusive national history.

Namatjira included himself in this series because he was trying

to understand the mindset of Indigenous men who volunteered for WW1 but were neglected and mistreated in their own country.

Visiting the royals

Wry humour and astute reversals of identity go a long way towards rewriting history and the effects of colonialism.

British royalty feature in numerous paintings, often with Namatjira inserting himself into the composition. He is having afternoon tea in the Royal Tour (Charles, Vincent and Elizabeth) (2020); and standing atop the royal carriage in The Royal Tour (Vincent and Elizabeth on Country) (2022).

The simple gesture of placing an uncomfortable Queen in someone else’s Country with Namatjira towering over her from the rooftop of the royal carriage says it all.

In another, Namatjira shows a dark-skinned and somewhat uncertain Charles on Country (2022), dressed in royal regalia and framed by an Albert Namatjira vista of the West Macdonnell ranges. The curatorial cues provided for viewers to read the imagery are in the artist’s own words. On royalty he says:

I’ve made a lot of paintings of the British royal family – that mob were born into wealth, power and privilege, so I feel it’s fair enough to make fun of their stuffy uniforms, and their outdated traditions … even their teeth.

Captain Cook too is a target – as a symbol of colonisation and empire, as he explains:

Over there is James Cook, his ship has washed up in the desert. He’s sunburnt, lost. British royals are out of place, wandering in the sandy creeks, among ghost gums.

Re-recording history

An especially powerful set of portraits, Seven Leaders (2016), are of senior Aboriginal men from the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands. They include Alec Baker, Kunmanara (Mumu Mike) Williams and Witjiti George.

Their white and greying hair and beards set against their dark skin, and their eyes full of experience and conviction, present an alternative set of powerful figures. Here, as in other paintings in this rich exhibition, the tables are turned – viewers come away questioning who has the power and why.

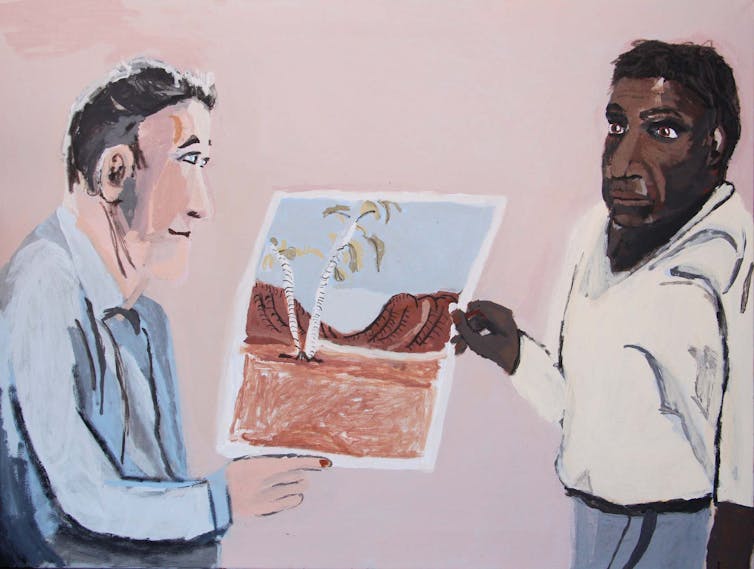

Sitting within the exhibition, Vincent Namatjira engages with the historical account of Rex Batterbee “teaching” Albert Namatjira the art of watercolour.

Vincent Namatjira’s rendition of this event, in which the transaction is one of cultural exchange, is a painting of equals.

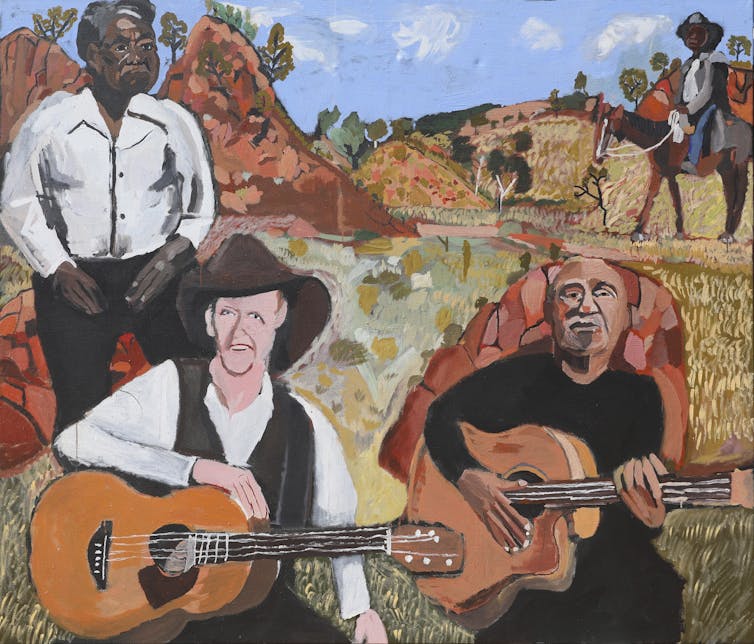

That engagement with art history extends to constructions of national art. In place of bucolic pastoral scenes of settled land – minus its Indigenous inhabitants – by artists such as Arthur Streeton are new national pictures such as Albert Namatjira, Slim Dusty and Archie Roach on Country (2022).

Collaborative pop-up books made with Tony Albert and irreverent portraits painted jointly with Ben Quilty, along with moving image work featuring Vincent Namatjira weaving through Country in Albert Namatjira’s trademark green truck, populate this lively, cheeky exhibition.

Its energy is infectious, its imagination extending to how things could be otherwise. Vincent Namatjira deserves the last word:

For me, the canvas is a setting where I can combine the past, present and possible futures, and I can put myself - as a proud Aboriginal man – at the front and centre of a situation where we would usually be out of sight.

Vincent Namatjira: Australia in Colour is on show at the Art Gallery of South Australia until January 21.

Catherine Speck has received from the ARC to research Australian art exhibitions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.