An amateur gold prospector in Victoria, Australia, recently discovered a gold nugget big enough to hold in two hands, worth around A$240,000. It was a lucky find, but he had chosen the right place to look.

Central Victoria was home to one of the world’s great gold rushes in the 19th century, which was focused mainly on the “golden triangle” northwest of Melbourne.

While that gold rush saw the extraction of thousands of tonnes of gold from Victorian soil, there is still plenty left. What some have called a “second gold rush” is now under way, as large mining companies and amateur fossickers use modern technology.

A rush and a boom

A road trip through Central Victoria’s Goldfields region takes you to 19th-century boom towns like Bendigo, Ballarat and Castlemaine. They are handsome towns, with elegant municipal buildings and graceful churches, the products of decades of wealth built on gold.

Rambling farther through Victoria, here and there you will find the ghost towns, such as Steiglitz, or the optimistically named Eldorado. These were less fortunate – their gold soon ran out.

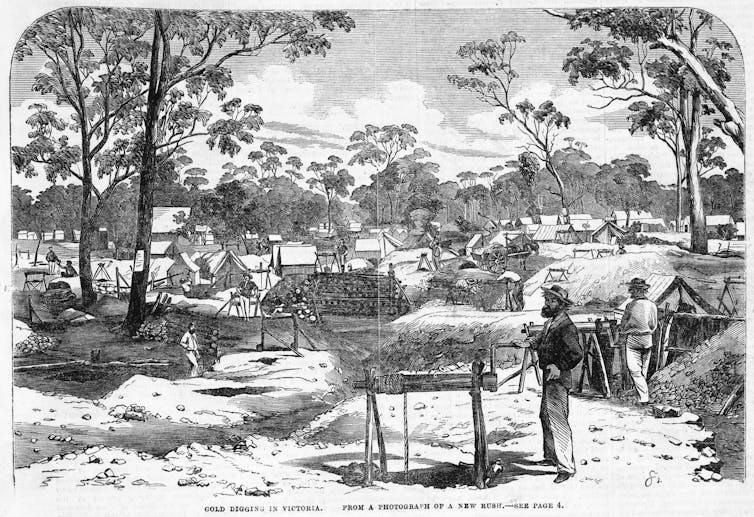

Victoria’s first gold rush took place during the 1850s and 1860s. Miners and prospectors poured into Victoria from across the world, colonising the lands of the traditional owners.

Some of these early gold hunters shovelled for small nuggets of gold sitting on the ground, or panned for flakes of gold floating in waterholes and creeks.

Others sought the underground source of the gold. They knew subterranean gold does not occur at random, but would be found in certain rocks.

When they found gold-bearing rocks breaking the surface, they dug for more. Then, they crushed the rock to get the gold out. It was skilled, difficult work that took a brutal physical toll.

How to hunt gold

In Victoria, most underground gold is found in “quartz reefs”: bands of hard white quartz. Formed some 400 million years ago, these gold-bearing reefs may be kilometres long, but are typically less than a metre wide, and slant steeply into the ground.

The places where these reefs break the surface were hard to find. But if the gold hunters were lucky and discovered a new reef, they could follow it a long way, along the surface and underground. The deeper the miners dug, the greater the risks of mine collapse, flooding, or other disasters.

Read more: How gold rushes helped make the modern world

Victoria’s remarkable gold rush history is the subject of a World Heritage bid. You can learn about the gold rush at Sovereign Hill in Ballarat, the Eureka Centre in Melbourne, and the Golden Dragon Museum in Bendigo, among other places. These places tell moving stories of the gold rush era: of colonial theft, of cruelty and exploitation, of skill, courage and hope.

Across the Victorian goldfields the gold rush had died down by the late 19th century. Even so, the most prosperous gold mines, such as the Central Deborah mine in Bendigo, continued to produce gold well into the 20th century.

But after the gold rush was over, the gold was still there underground. It was just harder to find, or harder to get at.

The second gold rush

Victoria’s second gold rush is less eye-catching and more high-tech than the first.

Mining companies from across the world are coming to Victoria, believing with modern methods they can find and dig up more of Victoria’s unusually pure gold.

Modern mines work with a current understanding of how rocks form, and of how the outer part of Earth deforms during the movement of tectonic plates. They use these ideas to predict the three-dimensional shape of the gold-bearing quartz reefs as they slant into the ground, making it easier to locate them deep underground.

Modern drilling methods make it easy to sample rocks, using machines like giant apple corers. And today’s techniques can extract more of the gold from the quartz that hosts it.

Today, Victoria’s gold mines produce around 650,000 ounces of gold each year, or about 20 tonnes. For comparison, at the height of the first gold rush, some 3 million ounces or around 90 tonnes were produced in 1856.

Many working mines hold open days for interested visitors, such as the Fosterville gold mine near Bendigo.

What to know if you’re hunting gold

Amateur gold hunting also flourishes on the Victorian goldfields today. “Fossicking”, or recreational prospecting, is a popular way to enjoy walks in the bush, with the possibility of taking home some gold or other treasure.

Dedicated fossickers may well invest in a metal detector, at a cost of several thousand dollars. For a more traditional approach, gold pans and sieves provide hours of fun for the patient, and are considerably cheaper than a metal detector.

Would-be fossickers should check their local regulations to find out if they need a licence. Once you have a licence, you must comply with its terms, which may put limits on fossicking activities, such as where you can look, what you can keep, and whether or not you can sell any finds.

You are still responsible for getting permission from the relevant landowners. As with any outdoor activity, you should be aware of the risks around you, including those posed by the weather.

In popular fossicking areas, you may be able to get advice on all of these things, as well as pointers towards finding gold, by joining a fossicking club.

If you aren’t lucky enough to live on a goldfield, don’t despair. You may still enjoy amateur prospecting or treasure hunting, looking for other precious metals or minerals, or even for hoards of gold coins.

Read more: Discovering a Viking hoard: a day in the life of a metal detectorist

I am exploring a research collaboration agreement with Kirkland Lake Gold Australia Pty Ltd.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.