Long before sunrise, dozens of people gather around more than 50 boats along this portion of Venezuela’s vast Caribbean coast, their tanned bodies showing scars and maimed hands from years of fishing. Most of them are men, but women are increasingly among them.

The women may be joining a family tradition of fishing, or in some cases launching new careers after losing jobs during Venezuela’s economic crisis, enlisting in the physically demanding work that may pay $8 after five consecutive 12-hour shifts.

That’s only a fraction of the estimated $390 that a Venezuelan family would need per month to buy a basic basket of goods in the South American country, but it is more than the nationwide $5 monthly minimum wage.

Once relegated to cooking or cleaning at hostels, bed-and-breakfasts and diners, women in the coastal communities of Choroni and neighboring Chuao have been gaining the respect of men with whom they now work to catch thousands of pounds of fish a day. Many of the women lost their jobs as the country’s protracted crisis all but ended the area’s tourism and the coronavirus pandemic worsened their living conditions.

“Nowadays, we have a big presence. In fact, there are women in the two fishermen’s councils, and there are women who own boats,” Greyla Aguilera, 48, said after finishing a recent shift.

The female boatowners “have strong character and almost all of their workers are women," Aguilera said. "With that, I do not mean that they give any preferential treatment to women because they really demand more from them than from men.”

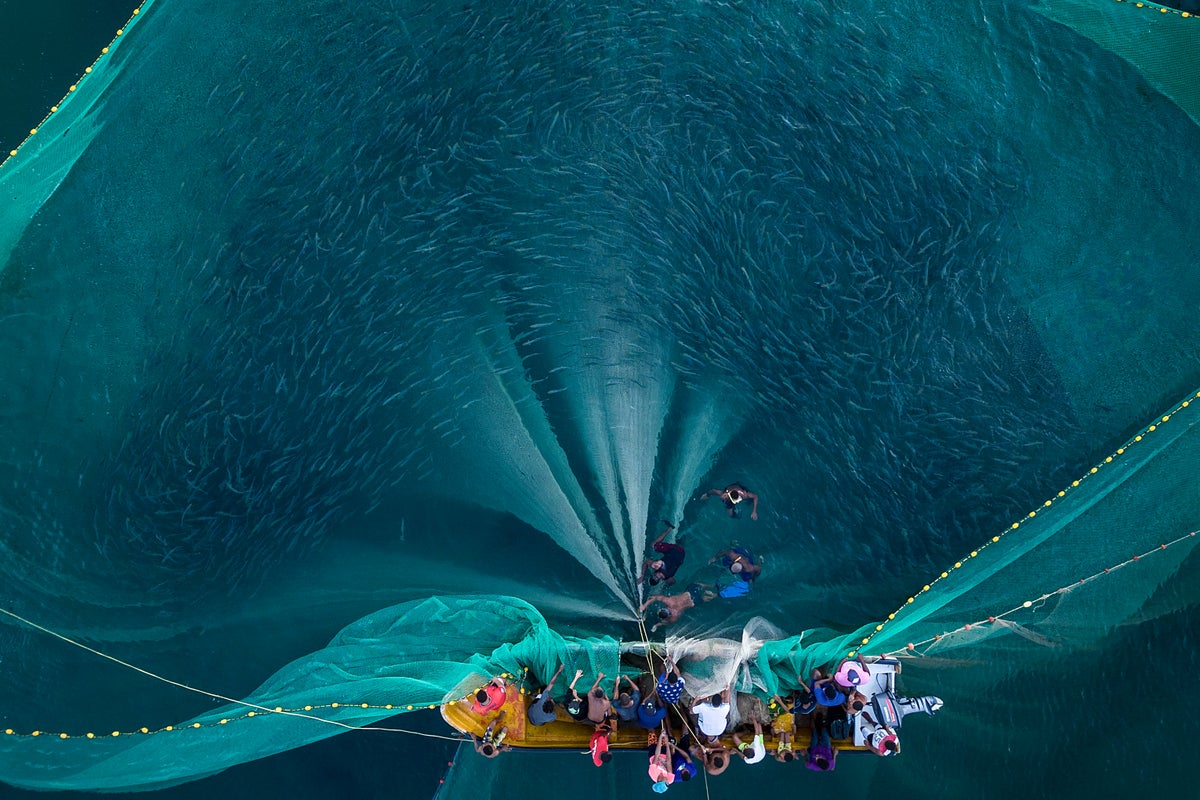

The fishermen and fisherwomen work in teams of four or five boats. They start by throwing a large net with some bait in the middle, which is then monitored regularly by a team diver. When the diver spots a shoal, the rest of the team throws a smaller net and begins to close it by pulling a drawstring-like line. The more they pull, the closer their boats get to each other, which allows them to move the fish from the smaller net to their boats. The fish is sold the same day at a nearby market.

The job requires a mix of patience, agility and courage. Accidents don’t happen often, but when they do, the lives and limbs of men and women are at risk.

Carolina Chávez started fishing at age 11 because her family needed food and became a full-time fisherwoman due to “lack of employment in our area.” She nearly lost her left hand two years ago when it became entangled with rope as she and others tried to lift a heavy net and their boats clashed. When she finally freed her hand, the rope cut off half of her middle finger. Her family would go hungry if she stopped working and, with no other options available, she returned to fishing shortly after.

Aguilera and her coworkers caught about 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds) during a series of June shifts for which she was going to be paid $7, but she took some fish home – a common practice among the workers – and asked the boat owner to deduct the cost from her pay, bringing it down to $5.

Choroni and Chuao, located west of Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, are sister communities with stunning beaches. Chuao is also the source of Venezuela’s most prized cacao, the raw ingredient in chocolate. But like other industries, chocolate has experienced a decline since the country’s crisis began last decade, pushing more people into fishing.

But to live off fishing alone is nearly impossible.

Some fisherwomen clean and process fish. Aguilera, who holds law and culinary degrees, tutors young children and teaches English lessons to older ones. She also photographs baptisms and first communions and is now testing recipes that incorporate cacao, coconut, lime and other regional crops with hopes of opening a café.

“It is very poorly paid,” Chávez, 43, said of the job she formally took up when she was 16.

Electricity goes out frequently in these coastal communities, and internet service is spotty at best. Public school teachers, severely underpaid across the country, show up to classrooms two or three times a week, and daycares are unheard of.

Aguilera said fisherwomen rely on each other and their parents to care for their children while they are at sea. Someone always steps up to ensure that no woman misses a fishing shift.

“The community is machista and matriarchal at the same time," Aguilera said.

“All women support each other, so if I see that you are in a hurry to take care of your children because your shift is coming up, I easily offer myself (to help you),” Aguilera said. "Your cousin offers herself and her grandmother offers herself, anyone, so that you can go fishing.”