Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum turns 50 in 2023. The museum, dedicated to the art of one of the most famous artists in the world, attracts over two million visitors each year.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

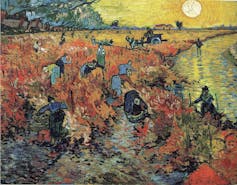

Yet, despite his fame today, Vincent van Gogh allegedly made only one documented sale of a painting during his lifetime. This was The Red Vineyard, produced near Arles in Provence in the autumn of 1888.

The enlightened buyer was Belgian painter Anna Boch, whose brother was a close friend of the artist. She spotted the vibrant landscape at the 1890 exhibition of the avant-garde group Les XX, of which she was a member.

This article is part of our Van Gogh Museum at 50 series. These articles mark the 50th anniversary of Amsterdam’s pioneering gallery and explore evolving cultural perceptions of one of the world’s most famous artists.

The price was 400 francs, the equivalent of around US$2000 (£1649) today, and would have seemed like a huge windfall to the struggling Van Gogh. If it were sold at auction today, the same painting could expect to fetch upwards of a hundred million US dollars.

Van Gogh dreamed of achieving posthumous fame and it was not long after he took his own life in July 1890 that the market for his pictures began to develop.

Boch went on to buy a second painting, Peach Blossom in the Crau, in 1891. In the same year Vincent’s art dealer brother Theo died of syphilis. Van Gogh had given a handful of works to the artists’ colour merchant Père Tanguy in Paris, but it was Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh Bonger, who would inherit the bulk of his vast oeuvre, making her the main source of his paintings.

As a result, she controlled the market for Van Gogh in Paris, Berlin, London and, eventually, New York.

Europe’s art market discovers Van Gogh

In 1901 the French poet Julien Leclercq, with Van Gogh Bonger’s assistance, organised the first Van Gogh retrospective at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris. The event brought Van Gogh to the attention of the German dealer Paul Cassirer, who went on to create a market for Vincent’s work in Berlin, supported by the influential art historian Julius Meier-Graefe.

By 1914 it was estimated that as many as 120 pictures by Van Gogh were in German collections and his work quickly increased in value.

In Britain, meanwhile, the art dealer with the closest links to Van Gogh was Alexander Reid. In 1887 Reid worked alongside Theo at the firm of Boussod & Valadon in Paris and briefly shared an apartment with both Van Gogh brothers.

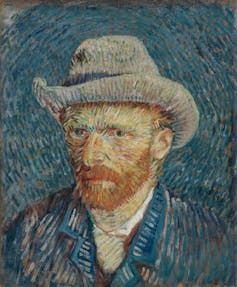

However, despite his close physical resemblance to the artist (two portraits of Reid by Van Gogh, now in Glasgow and Oklahoma, were originally catalogued as self-portraits), it was not until the early 1920s that he began to exhibit and sell his pictures to rich industrialists in Glasgow and London. Among the most significant was the Scottish collector Elizabeth Workman, the wife of a successful ship owner.

The most important early collector of Van Gogh’s work was another enlightened woman, Helene Kröller-Müller, who – although German by birth – was based in Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

Advised by the Dutch painter and critic Henk Bremmer, she bought her first work by Van Gogh in 1908. Supported by her industrialist husband Anton (who was initially sceptical of her new-found passion), she went on to acquire no fewer than 91 paintings and over 180 works on paper.

Along with Cassirer, Bremmer helped to push up the price of Van Gogh’s work. As a result, fakes began to appear in various galleries and exhibitions. The most famous forgery case was that of the dancer-turned-art dealer Otto Wacker, who was brought to trial in Berlin in 1932.

Van Gogh’s art market goes global

As the market for Van Gogh’s pictures increased, the importance of establishing the authorship of a painting or drawing became even more crucial.

In the 1980s, with the advent of the Japanese craze for Van Gogh, his work began to fetch world records at auction. In 1987 there was huge public debate around the authenticity of the Sunflowers acquired by the Yasuda Marine Insurance company in 1987 for US$39.9 million.

Three years later the Japanese businessman Ryoei Saito paid the record price of US$82.5 million for the Portrait of Doctor Gachet. Most recently this record was smashed in November 2022, when a Van Gogh landscape of Arles from Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s collection sold for US$117 million to an anonymous bidder.

Today the Van Gogh Museum has the last word when it comes to authenticating the artist’s work. The Yasuda Sunflowers are now believed to be authentic, based on the picture’s provenance, which can be traced back to Jo van Gogh Bonger.

A more recent “discovery” of a portfolio of Van Gogh drawings in 2016, however, has not yet been accepted as genuine. But what is it about Van Gogh’s work that remains so compelling to prospective buyers, over 130 years after his death?

Today, as we are encouraged to focus on mental health, his work seems to have more relevance than ever. Whatever the reason, and despite the scorn that he endured during his lifetime, the market continues to be seduced – like Boch all those years ago – not only by his tragic personal story, but also by his artistic genius.

Frances Fowle does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.