THE world's fastest man on water Ken Warby has reportedly died in the United States this week.

News of the Hunter man's passing after a short illness came on Tuesday.

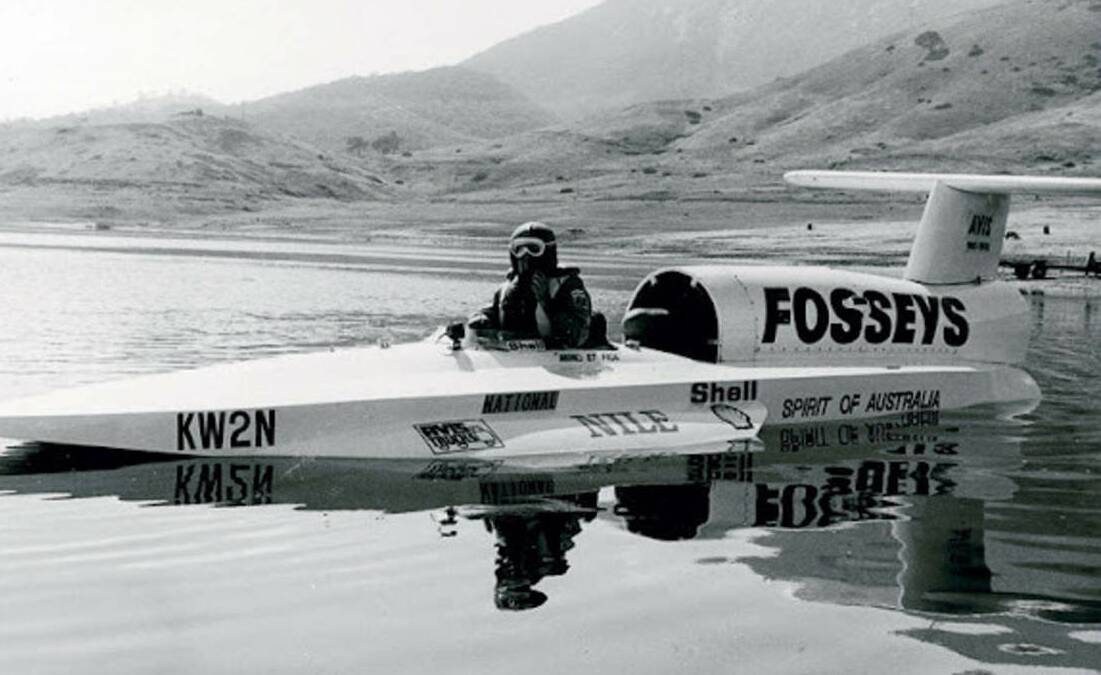

Mr Warby set the world water speed record of 511.1km/h in a boat he designed, built, financed and piloted himself in 1978.

Here is his story told in the words of father and son from the Newcastle Herald archive: February 20: 2015

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON: by John Huxley

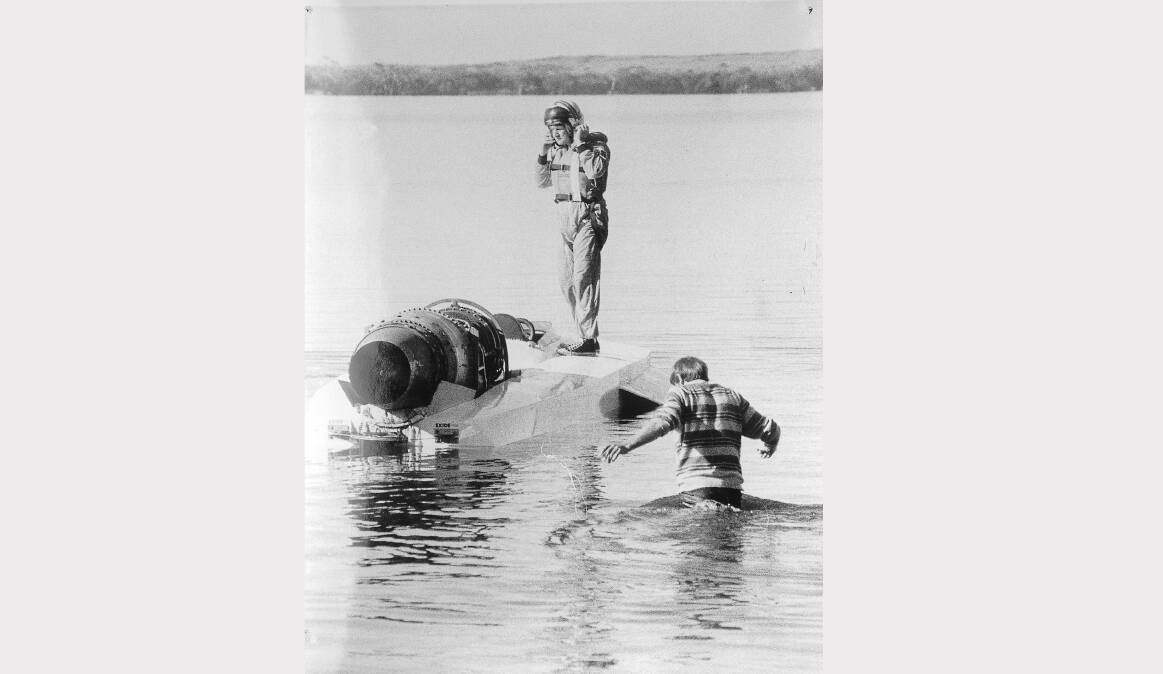

Though it happened almost 40 years ago, David Warby still recalls vividly the day his father, Ken, became the fastest man on water driving a wooden boat designed on a kitchen table, powered by a $65, second-hand engine, and built in the backyard of the family home in the Sydney suburb of Concord.

On the afternoon of the world-record attempt, on Blowering Dam near Tumut in the Snowy Mountains, David and his two brothers were kept at home with their mother, Jan. Although Kens parents were present on the dam foreshores for the record attempt, his mother kept her eyes scrunched closed throughout.

I can understand all that now, says David, who was nine at the time. Dad didnt want us there if anything went wrong.

Over the years, the deadly game of water speed record-breaking, as Ken calls it, has claimed the lives of almost a dozen challengers before and since, including that of British speedster Donald Campbell, who died in 1967 in Englands Lake District trying to emulate his famous father Sir Malcolm.

Recalls Dave: On the big day people stopped me in the street. Havent you heard? It says on the radio yer dads broken the world record. It was amazing. That was in November 1977. The following year Ken Warby returned to Blowering, having tweaked his boat Spirit of Australia which remains a star attraction at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney and broke his own record with a run of 511.13km/h, or about seven seconds per kilometre.

Suddenly, the impoverished Warbys were world-famous. Ken was made a member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) and was given a sum of money by then Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser to promote Australia. He appeared on This Is Your Life and met his hero, country singer-songwriter Slim Dusty, whose cassettes he still plays incessantly in his car.

But his marriage broke up. Jan and I just grew apart, explains Ken, now 75. An introvert, she hated the danger, stress and media attention associated with record chasing as much as he an affable extrovert loved them all.

Moreover, he needed to make a living. A self-taught engineer and boat builder, who had worked in the 1970s as manager of BHPs lubrication department in Newcastle, Ken soon discovered that breaking records would not make him and his young family rich. In the early 80s, he abandoned hopes of winning sufficient sponsorship in Australia and struck out to the US to do what he did best: design, build and race fast cars, trucks and boats. He still lives in Miamitown, south of Cincinnati, Ohio, with his second wife, Barbara. He also has a ready-mix concrete business.

The rest of the Warby family stayed in Australia. Mum didnt want to bring us up in America; thank goodness, jokes David, who combines boat building and engineering with part-time work in community services in Newcastle.

Ken remained a regular visitor to Australia and staged a further record attempt in 2003, which had to be abandoned after a dispute with motor boatings governing body, the Union Internationale Motonautique, over safety features on his new boat, Aussie Spirit. Four years later he reluctantly announced his retirement from record-breaking.

Though Ken and Barbara still race boats, the decision seemed to mark the end of what the fast man called his magnificent obsession with breaking records. Not so.

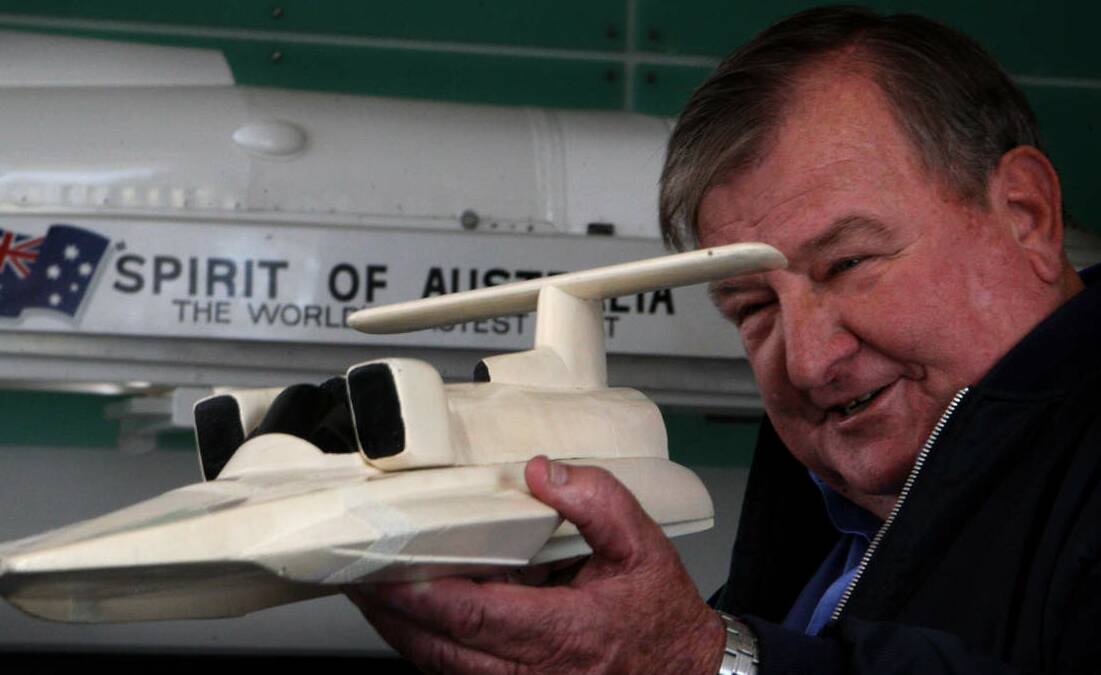

In a temporary workshop on an industrial state in Wickham, shared with bikies, panel beaters and car repairers, father and son are now working side by side, building a new boat Spirit of Australia II for a new driver: 46-year-old Dave.

Although the wooden boat resembles its predecessor, it is slightly longer and lighter to carry a jet engine taken from an Italian Fiat Gina G-91 fighter plane, explains Ken. The new boat will be 50per cent more powerful, lighter, faster and, in theory at least, far, far safer. When Dad went on the water, he sat on a 10-mil [millimetres] thick piece of plywood with a bit of foam on it, says Dave.

By contrast, Dave will sit in a six-point safety harness, contained within a purpose-built carbon/Kevlar cockpit that is equipped with radio, fire extinguisher and water-activated EPIRB personal locator. He will also be accompanied by a team of rescuers, divers and experts whose job will be to look out for patches of choppy water that could tip Spirit of Australia II over in its dash across the dam. But such precautions, designed to meet exacting international safety requirements, can only go so far.

Ken explains bluntly the risk facing Dave as he seeks to rewrite a long-standing entry in Guinness World Records. Hes got to understand hes putting his life on the line, he explains as the pair hoe into healthy plates of caesar salad at the local pub. He may never come back. If you dont understand what can happen when you put your foot on the throttle, you shouldnt put your arse in the cockpit.

Dave nods in agreement as Dad continues, When you sit at the end of Blowering with that long stretch in front of you, the one question you must answer is, How badly do you want it? Dave nods again. He knows the risks. He knows shit can happen when youre going 300, 400, 500, even 600 km/h on water. We do as much as we can to make sure its safe, says Dave. But the biggest safety feature you can have is knowing the design is right. If itd been designed and built by someone else, youd have doubts. But I know every nut, bolt and bit thats being put into this boat.

Despite a limited budget the pair have so far spent about $280,000, buying materials and jet engines, shipping them around the world and paying for Kens commute from the US Dave insists nothing is being left to chance.

Spirit of Australia II bears all the hallmarks of its world-beating predecessor, according to Bill Richards, who has known the pair for more than 20 years. Ken brings inspiration and invaluable design and building experience to the project, while Daves got a great understanding of contemporary materials and building techniques.

As youd expect, they take each step with extreme care and confidence, says Richards, a former media manager of the National Maritime Museum. Theres an occasional father-and-son glitch, differences of opinion, but theyre usually sorted out with a touch of good humour.

Though Dave has not raced anything faster than a 240km/h hydroplane powerboat, he has long held an ambition to take on the world. He has served a long apprenticeship, working with Ken on his jet cars, rebuilding a V8 hydroplane Diablo in his 20s and building several boats of his own. As a youngun, I idolised Dad. He was my hero, my inspiration. But he never pushed me into it. Hed say, Yeah, well, cars and trucks, perhaps one day, but stay away from the boats.

Sound advice, bearing in mind that 11 men, including American friends Lee Taylor and Craig Arfons, have died trying to beat Ken Warbys 1978 record which still stands today.

So why, at 46, is Dave jumping into what should be the worlds fastest boat? He has spent a lifetime studying boat records, times, designs. He enjoys building and racing them. Most of all, he wanted to work alongside his father again. I dont really want to take a record off him. I want to remind people of his marvellous achievement all that time ago. He built his boat with just three power tools.

Forty years on its still at the cutting edge. You could say were not reinventing the wheel, were refining it.

And how does his mum, Jan, feel? Shes rapt. Shes worried about my safety, naturally, but very happy that Dad and I are doing something together. As in 1977, Jan will wait at home for news of her sons attempt to beat his fathers record. But one big fan is sure to be on Blowering Dams shores: Daves long-time partner, Lesa. Shes been very supportive, says Dave.

Almost simultaneously, Dad and Dave consult their watches. Its time to return to shaping the ultimate motorboat and its master. Having turned down the offer of a beer 45 minutes earlier, the pair have munched slowly through their light salads. Now they politely refuse a dessert. Were both on diets. In fact, Ive lost 14 pounds [6 kilograms], says Ken proudly.

If Dave gets nervous on the big day, I want to make sure Im in good shape to jump in the cockpit at short notice.

NOTE: The Spirt of Australia was aquired by the National Maritime Museum in 1983, where it remains to this day.

To see more stories and read today's paper download the Newcastle Herald news app here.