The war for the future of Starbucks is reaching a peak in a café just a short walk from where the coffee juggernaut was founded.

The battlefield is the chain’s flagship Roastery on Seattle’s trendy Capitol Hill, a sprawling 15,000 sq ft space where visitors can order coffee cocktails and watch beans destined for cafés across the world being ground in its roasting area. Staff say it is where Howard Schultz, the outgoing chief executive who helped build the company into a multinational giant, buys his coffee beans.

It was also among the first of hundreds of Starbucks stores to launch a drive for union representation this year, and where union organisers say the company has fought the effort the hardest. Workers voted in favour of the union in April.

“This is the crown jewel on the hill,” says Elizabeth Durand, one of the Roastery’s shift supervisors. “We’re knocking on Howard Schultz’s front door and he’s scared. He doesn’t want to concede it.”

First, employees say they were instructed to come in before their regular shifts to sit through hour-long meetings about the union with managers. Next, they learnt that the chain planned to exclude staff at unionised stores from nationwide pay rises. And then, after the newly formed union sent Starbucks a request to negotiate in July, Starbucks said it would issue a legal challenge to the union’s election victory.

In a statement, Starbucks said that “Our hope is the union would respect our right to share information and our perspective just as we respect their right to do so.”

The upstart union, Starbucks Workers United, is one of a new breed of organised labour that has emerged in the US in recent months. The movement has traditionally been dominated by large, sector-specific unions such as the United Auto Workers, the Service Employees International Union and the Teamsters, which have maximised their scale and reach to fight for better conditions for workers.

Instead, the Starbucks employees have taken a different approach — forming smaller groups led by workers on a store by store basis, in the hope that it will build to a broader movement. The strategy has attracted a younger, more politically engaged type of worker, and has helped unions gain a foothold not just in the coffee giant, but also in Amazon, Chipotle and others following a similar path.

Labour leaders see the battle at the Roastery as a crucial test of whether these nascent unions hold the key to reviving the wider United States labour movement.

The Covid crisis and the labour shortage that ensued gave many US workers newfound leverage over their bosses, allowing them to bargain for higher wages and better working conditions. But established unions have struggled to capitalise on their surging popularity and political goodwill since the start of the pandemic.

The less traditional unions, by contrast, have grown rapidly. Since baristas in Buffalo, New York, founded Starbucks Workers United last December, some 233 other locations have followed suit. Workers at Amazon, Chipotle, and Trader Joe’s have all cited the union’s speedy rollout as the inspiration behind their own drives.

But none of the new Starbucks unions have successfully completed what labour scholars say is the most important step on the path to unionisation: negotiating a collective bargaining agreement, the legally binding contract that unions rely upon to improve conditions for its members.

The Seattle baristas came the closest, negotiating with corporate to secure new positions for employees who worked in cafés that the company closed. Their colleagues in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania later did the same.

If one of these worker-led, grassroots unions can secure a contract, it could “be the spark to show the national labour movement about union strategy”, says Jake Grumbach, a professor of political science who also researches labour at the University of Washington.

“These are big debates in the labour movement. Should we be more ‘small d’ democratic’ and let the rank and file workers determine what the union does or should it be run more in a centralised way? Should we get into politics like minimum wage battles or should it just be involved in bargaining for wages and health benefits and retirement for the workers?”

At a time when the relationship between employees and employers globally is under pressure from rising inflation and changing worker expectations, what happens in Seattle may have wide repercussions.

“There’s potentially a real hunger for this and there’s a lot of opportunities to organise in unexpected places,” Grumbach adds, “so this may shift union strategies nationally.”

The ‘hot labour summer’

Far fewer US workers are members of a trade union than in many other major democracies, at 12.9 per cent, according to the OECD (in the UK, the figure is about 23 per cent). The number has been steadily declining for decades.

Many union members work in manufacturing or public sector roles such as education and healthcare. But rising inequality has reignited some private sector workers’ interest in unions in recent years, and workers’ rights came into even sharper focus during the pandemic.

“In times when people are feeling insecure about their jobs, about their incomes, about what’s going to happen to them at work, that is the time when [the] union message does tend to resonate more strongly,” says attorney Dan Altchek, who represents employers in labour disputes for Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr.

“That was something that people who do management-side labour relations were calling out in March, April, May of 2020, that employers that would want to remain union-free should think about how they treat their workforce.”

Many did not listen, Altchek says. A surge of union activity ensued. The federal agency that oversees worker representation in the US — the National Labor Relations Board — reported a 57 per cent increase in petitions for union elections filed during the first six months of fiscal year 2021.

Workers have become bolder at taking action, too. Some 180 strikes were held in the first half of this year according to Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker, a 76 per cent increase over the same period in 2021. In one high-profile action, Chicago public schools closed for five days in January when members of the teachers’ union stayed home to protest for stronger Covid precautions.

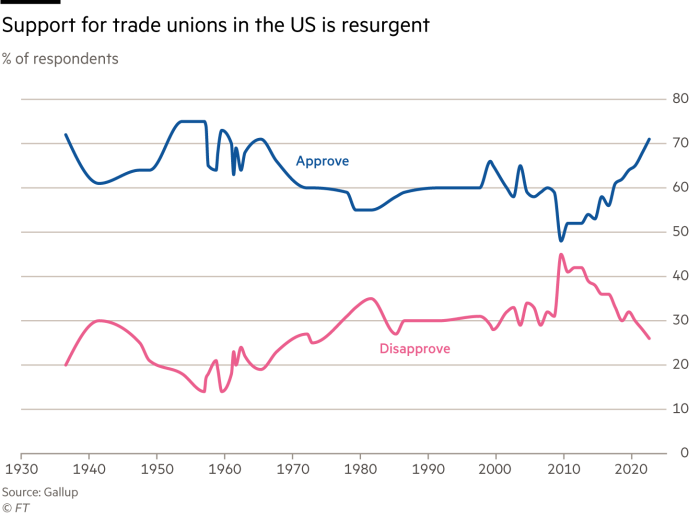

And despite the disruptions those strikes caused, organised labour is more popular with Americans than it has been since at least 1965. In an August poll, Gallup reported that 71 per cent of the country say they approve of unions. That is up from 64 per cent before the pandemic.

Activists have dubbed the season “hot labour summer”.

The problem for the US labour movement is that while workers’ attitudes towards unions are improving, many say they are not interested in joining one themselves. Some 58 per cent of non-union workers in the US say they are “not interested at all” in joining one, Gallup reported.

“[For] all of the outstandingly inspiring Starbucks and Amazon and Chipotle workers, we have to be real,” Grumbach says. “It’s not actually a major change in union concentration in the US. Whether this is a lasting shift or some kind of Covid-triggered blip remains to be seen.”

Barista blues

The conditions were ripe last year for Starbucks’ unionisation drive. The pandemic put the company “under significant pressure”, Schultz told investors in May, shortly after he returned to the company for his third stint as chief executive.

Increased competition and Covid restrictions propelled the company away from Schultz’s original dream of being a “third place” for people to socialise after their homes and workplaces. Starbucks increasingly pushed mobile orders.

But baristas say this made their jobs almost impossible. “It’s honestly one of the most difficult jobs that I’ve ever had in the service industry,” says Casey Moore, who works at a café in Buffalo. Her store held a union election in May, but the outcome is still in dispute. “I’ve been a waitress and a bartender and nothing compares to the pace and the intensity of being a Starbucks barista.”

Starbucks’ stores were “not set up” for the work-from-home era when drink orders are increasingly customised, iced, and ordered for mobile pick up or delivery, Schultz said.

Frustrated baristas in Seattle circulated a photo of one order they say encapsulates the trend; a customer had mobile ordered a Mango Dragonfruit Refresher with coconut milk, no ice, and added water, apple juice, and strawberry purée, plus pumps of hazelnut, peppermint, toffee nut, and raspberry syrups all to be blended together. Union representatives say that orders like that can put the barista preparing drinks behind on other tasks by as much as 15 minutes.

And the number of orders is rising. Starbucks’ US net sales rose 9 per cent over the quarter ending July 3, and the company’s earnings beat Wall Street’s expectations. Employees, called “partners” by the company, wondered if they should share in that success.

“I was working my butt off every single day, physically, mentally, emotionally, just dealing with customers and running around,” Moore says. “I kind of realised that I’m putting in all of this work and this is a multibillion-dollar company and I’m just making it by. Why is that the case? I can do something about that. And unionising was kind of the way that we all saw that we could do that and build power for us.”

Instead of working with one of the major unions that tried for years to organise fast food workers with minimal success, the baristas founded their own union, in collaboration with the 86,000-member Workers United union.

The result is an organisation that is substantially younger and more diverse than the stereotypical working-class union member in the US, whom Grumbach describes as a middle-aged “white guy in a hard hat”.

Starbucks Workers United’s TikTok videos showing a young, diverse group of workers on picket lines have garnered millions of views. Memes on their Twitter feed compare Trump’s rejection of the 2020 election results to Starbucks’ legal challenge of the union’s election victory at the Roastery and ask followers to spot the difference.

The group might also be more effective at recruiting new members. The union’s expansion across the country has been “remarkable”, Altchek says, and they did it with little help from professional labour organisers. The workers who co-ordinate the Seattle-area chapter of the union go café to café in their spare time passing out union pamphlets to fellow baristas.

Support for Starbucks Workers United has been particularly strong in the Pacific Northwest, bolstered by the region’s left-leaning politics, high education rates and long history of labour activity, Grumbach says. Union representatives said they have won approximately 95 per cent of their elections there, compared with 85 per cent nationwide.

Grounds for conflict

The real test of the influence of Starbucks Workers United on the broader labour movement will be if they can bring the company to the bargaining table, says Kate Andrias, a Columbia Law School professor who studies organised labour.

But the relationship has grown increasingly hostile. The union has accused Starbucks of illegally firing union leaders and closing unionising stores, and has filed hundreds of complaints against the company. The coffee chain alleges federal labour officials have conspired with the union to fix election results.

The atmosphere has poured cold water on the unionisation drive; the number of Starbucks stores filling for new union elections each month has steadily declined from a peak of 71 in March, to eight in August.

Starbucks denies that it has acted illegally in the course of its union avoidance campaign. The company previously said that the fired partners were let go for reasons other than their union work, and that labour laws prevented it from including union-represented workers in nationwide pay rises.

The coffee chain said last month that a “career professional” at the NLRB had approached it with evidence that board officials in Kansas City worked in concert with union leaders to share information about confidential mail-in ballots. While the NLRB said it does not comment on open cases, the union has called the allegations “absurd”.

The US legal system arguably favours corporations in such confrontations. A series of conservative laws starting with 1947’s Taft-Hartley Act have given employers more tools to fight unions, and restricted the ways workers’ can organise. Some European countries allow union representatives to take a seat on a company’s board, or administer unemployment benefits, unlike in the US.

While employers are legally required to negotiate “in good faith” with the union that represents their workers, the penalties for breaking the law are slight, and it is not uncommon for employers to refuse to bargain at all.

Workers have the right to go on strike under federal law; Starbucks workers in at least 17 states have held strikes over firings of employees who were involved in the union and disputes over benefits. The Seattle Roastery held a day-long strike in July, protesting the closure of two unionised stores nearby.

But employers are permitted to hire replacement workers and are often not required to reinstate striking workers until new job openings become available.

Complaints of labour law violations have been more aggressively pursued by federal officials under the Biden administration. The NLRB has filed 23 complaints against Starbucks, including two in Seattle.

The agency has only won one of its cases thus far, when a court ordered that seven workers in Memphis who were fired after getting involved with the union be rehired.

Without more help from regulators, the Starbucks union will have to find a way to motivate bosses to come to the bargaining table, Andrias says. The company has also hired a new chief executive, Laxman Narasimhan, from UK-based health product maker Reckitt Benckiser. The union says they hope that he will be more co-operative than Schultz after he starts on October 1.

History does not suggest a speedy resolution, however; between 1999 and 2003, a majority of new unions had not signed a collective bargaining agreement one year after their election, according to a study by Kate Bronfenbrenner of Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

The difficulty of winning over employers is one of the major reasons the US labour movement has stagnated, Andrias says. “What we’re seeing is the result of that gap between what workers want and what the legal regime in the United States makes possible,” she adds. “The challenges can be overcome, and I’m confident that they will be overcome by Starbucks workers.”

Even if the union is never able to successfully negotiate an employment contract, some Starbucks workers say the effort has been worth it just to show the world the inequalities inherent in low-wage work.

“There’s just a sort of assuredness that you have when you know you’re standing on the right side of history,” says Sarah Pappin, who works at a Seattle café just blocks from the chain’s original location at Pike Place Market. “I’m gonna keep fighting, no matter what they throw at me until we get there.”

Additional reporting by Michela Tindera