Visitors to a US military cemetery in the southern Netherlands have voiced strong objections after two displays honouring Black troops, instrumental in liberating Europe from the Nazis, were removed.

The American Battle Monuments Commission, a US government agency, took down the panels from the visitors' centre at the American Cemetery in Margraten sometime in the spring. This site, a resting place for approximately 8,300 US soldiers, is nestled in rolling hills near the Belgian and German borders.

The decision followed a series of executive orders issued by U.S. President Donald Trump, which aimed to dismantle diversity, equity, and inclusion programmes. In a March address to Congress, Trump declared: "Our country will be woke no longer."

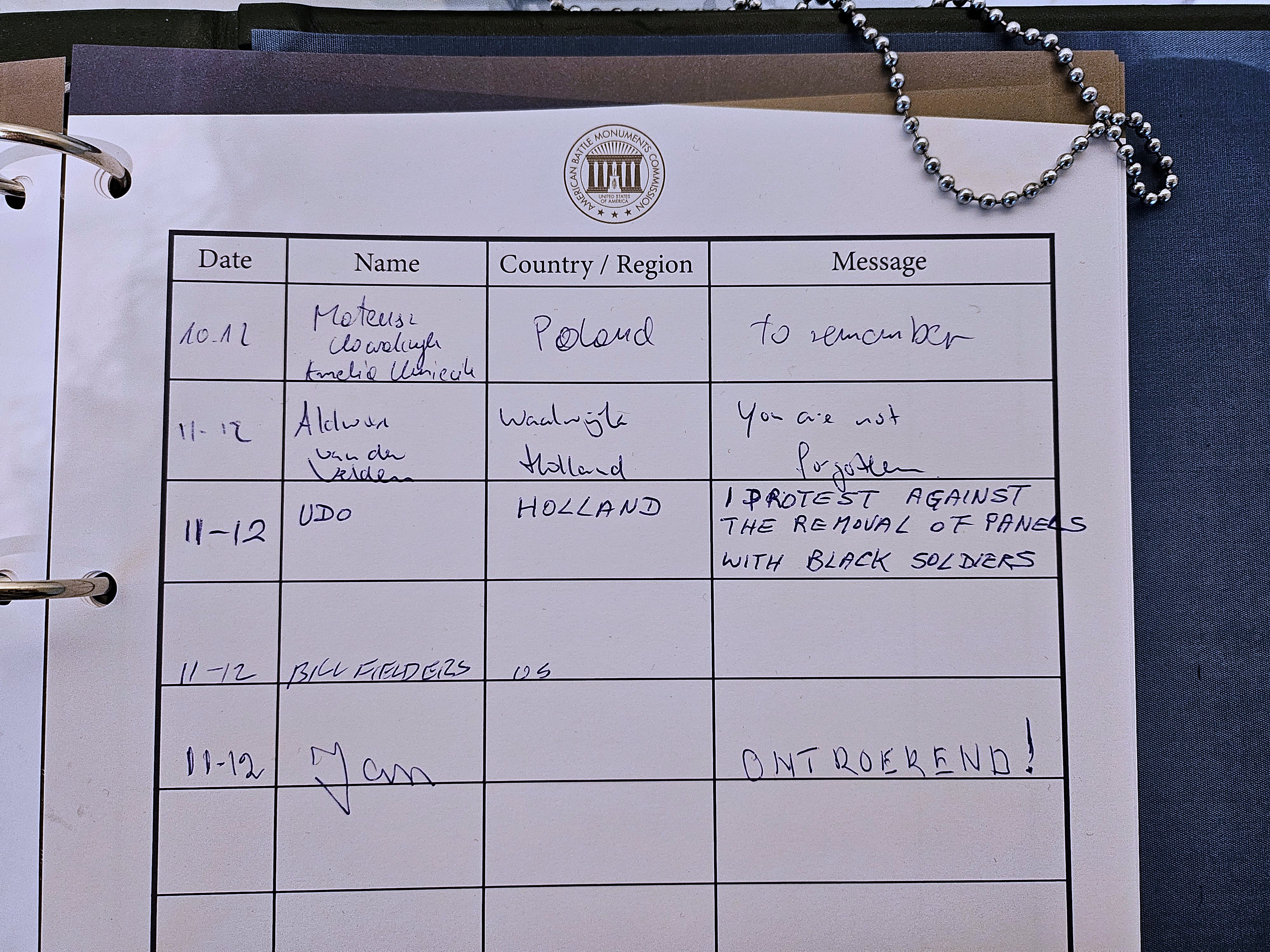

Carried out without any public explanation, the removal has provoked anger among Dutch officials, the families of US soldiers, and local residents who honour the American sacrifice by tending to the graves.

U.S. Ambassador to the Netherlands Joe Popolo seemed to support the removal of the displays. “The signs at Margraten are not intended to promote an agenda that criticizes America,” he wrote on social media following a visit to the cemetery after the controversy had erupted. Popolo declined a request for comment.

One display told the story of 23-year-old George H. Pruitt, a Black soldier buried at the cemetery, who died attempting to rescue a comrade from drowning in 1945. The other described the U.S. policy of racial segregation in place during World War II.

Some 1 million Black soldiers enlisted in the U.S. military during the war, serving in separate units, mostly doing menial tasks but also fighting in some combat missions. An all-Black unit dug the thousands of graves in Margraten during the brutal 1944-45 season of famine in the German-occupied Netherlands known in the Hunger Winter.

Cor Linssen, the 79-year-old son of a Black American soldier and a Dutch mother, is one of those who opposes the removal of the panels.

Linssen grew up some 30 miles (50 kilometers) away from the cemetery and although he didn’t learn who his father was until later in life, he knew he was the son of a Black soldier.

“When I was born, the nurse thought something was wrong with me because I was the wrong color,” he told The Associated Press. “I was the only dark child at school.”

Linssen together with a group of other children of Black soldiers, now all in their 70s and 80s, visited the cemetery in February 2025 to see the panels.

“It’s an important part of history,” Linssen said. “They should put the panels back."

After months of mystery around the disappearance of the panels, two media organizations — the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) and online media Dutch News — this month published emails obtained through a U.S. Freedom of Information Act request showing that Trump’s DEI policies directly prompted the commission to take down the panels.

The White House did not respond to queries from AP about the removed panels.

The American Battle Monuments Commission did not respond to queries from AP about the revelations. Earlier, the ABMC told the AP that the panel that discussed segregation “did not fall within (the) commemorative mission.''

It also said that the panel about Pruitt was “rotated” out. The replacement panel features Leslie Loveland, a white soldier killed in Germany in 1945, who is buried at Margraten.

Chair of the Black Liberators foundation and Dutch senator Theo Bovens said his organization, which pushed for the inclusion of the panels at the visitors center, was not informed that they were removed. He told AP it is “strange” that the U.S. commission feels the panels are not in their mission, as they placed them in 2024.

“Something has changed in the United States,” he said.

Bovens, who is from the region around Margraten, is one of thousands of locals who tend to the graves at the cemetery. People who adopt a grave visit it regularly and leave flowers on the fallen soldier’s birthday and other holidays. The responsibility is often passed down through Dutch families, and there is a waiting list to adopt graves of the U.S. soldiers.

Both the city and the province where the cemetery is located have demanded the panels be returned. In November a Dutch television program recreated the panels and installed them outside the cemetery, where they were quickly removed by police. The show is now seeking a permanent location for them.

The Black Liberators is also looking to find a permanent location for a memorial for the Black soldiers who gave their lives to free the Dutch.

On America Square, in front of the Eijsden-Margraten city hall, there is a small park named for Jefferson Wiggins, a Black solider who, at age 19, dug many of the graves at Margraten when he was stationed in the Netherlands.

In his memoir, published posthumously in 2014, he describes burying the bodies of his white comrades who he was barred from fraternizing with while they were alive.

When Black soldiers came to Europe in the Second World War, ’’what they found was people who accepted them, who welcomed them, who treated them as the heroes that they were. And that includes the Netherlands,″ said Linda Hervieux, whose book “Forgotten” chronicles Black soldiers who fought on D-Day and segregation they faced back home.

The removal of the panels, she said, “follows a historical pattern of writing out the stories of men and women of color in the United States."

Ukrainian POWs ‘being systematically executed’ by Russia, says top commander

Trump ‘not worried’ even as China fires rockets towards Taiwan during war games

In Pictures: A year of royal resilience and resolution

NYC teachers stunned to learn students can’t read old clocks amid phone ban

More artists cancel on Kennedy Center in protest of Trump adding his name

US military strikes another alleged drug boat as Trump ramps up Venezuela pressure