For months economic and sharemarket chatterers have been yelling at the US Federal Reserve to lift interest rates to control rapidly rising inflation. (Australia’s pale imitation of the same gang of noisy miners have made similar calls for the Reserve Bank to lift rates — and be reviewed post-election for failing to heed their yells.)

The surge in inflation for most of the past year was the driver of the first rate rise since 2018. The all-knowing economic commentariat have claimed the Fed “was behind the curve”; now with the statement and forecasts, it has silenced the chatterers.

The rate rise was overshadowed by the Fed making clear there could be six more this year, a prospect many economists had forecast but never thought would happen — especially as the central bank made it clear there would be a cost to economic growth (something all the yellers for rate rises rarely concede) in an election year that will make holding on to control of the US Congress for the Democrats that much tougher.

Most of the Fed’s December 2022 forecasts changed, with inflation higher and growth lower — but interestingly there was no change in its unemployment forecast of 3.5%. It sees unemployment easing from February’s 3.8% over the rest of this year, despite slowing activity.

The extent of the trade-off between growth and inflation was shown in the new forecasts. The Fed now projects 4.3% core inflation in 2022, up from 2.6% in December. It expects that to ease to 2.7% in 2023 and 2.3% in 2024, but those are also above its December projections.

For economic growth, the Fed sees 2.8% GDP growth in 2022, down from 4% in its December projections, and 5.7% real GDP growth for 2021. So to get inflation back under 3% by next year from 4.3%, GDP growth will be flattened and the growth rate cut in half by the end of this year. And yet the Fed sees no change in unemployment.

Fed chair Jerome Powell acknowledged the big jump in inflation expectations, saying “inflation is likely to take longer to return to our price-stability goal than previously expected”.

He added that “participants continue to see risks as weighted to the upside” on inflation — a hint that the bank could, if it sees the need, turn a 0.25% rate rise at a future meeting into a 0.5% increase, according to US economists.

“The signal from the dots is hawkish — it means they’re willing to sacrifice growth for inflation. They have to slow growth to achieve that outcome,” said Mark Cabana, head of rates strategy at Bank of America. He got that right.

But a different view came from another top US business economist, David Kelly, chief global strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, who told CNBC on Wednesday he believes the Fed is overdoing it by projecting six more interest rate hikes this year.

“I’m not surprised the Dow is down. I think this is a very aggressive move,” he said, alluding to the fact the 30-stock average briefly went negative as investors processed the Fed’s post-meeting statement.

Wall Street ended up handing the decision its version of a standing ovation. The Dow surged to end the day up 518 points. The S&P 500 also rose strongly, as did the Nasdaq, up 3.7%.

Powell also indicated the Fed’s massive bond buying (quantitative easing) would end shortly and it will soon announce how it is going to reduce its US$7.17 trillion balance sheet. The betting is a mixture of rolling over and running off bonds — in other words a small, ongoing policy tightening to accompany a rapid-fire (relatively speaking) series of rate rises.

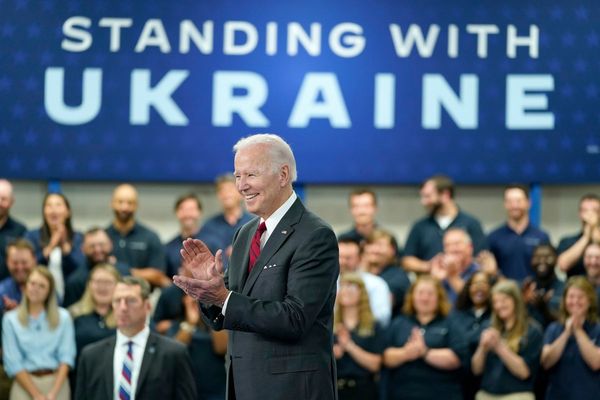

This is a very real example of the central bank’s independence, especially as the Democrats and President Joe Biden face a tough set of mid-term elections in November with right-wing Republicans led by the Trump gang hungry to take control of Congress.

Such a tough policy call from an independent central bank is something many in the Morrison government — and some in the ALP (Andrew Leigh and his svengali Paul Keating) — want to limit via a review of the Reserve Bank.

The US Federal Reserve expects inflation to return to 2%, but the comeback will take longer than initially expected, Powell said.

“As we emphasise in our policy statement, with appropriate firming in the stance of monetary policy, we expect inflation to return to 2%, while the labour market remains strong,” he said.

When asked what would trigger the Fed to adjust the pace of its rate hikes, he said it could speed up its plans if more aggressive monetary tightening was needed.

“The way we’re thinking about this is that every meeting is a live meeting,” he said. “We’re going to be looking at evolving conditions, and if we do conclude that it would be appropriate to move more quickly to remove accommodation, then we’ll do so.

“I can’t be perfectly specific about it. But that’s certainly a possibility as we go through the year.”