The Southern Auckland Economic Masterplan lacks ambition, insight and creativity and, given its scale, it desperately needs those defining attributes

Opinion: Auckland will be home to 2.4 million people by 2050, according to local and central government modelling. That means 700,000 more residents will need homes, jobs, amenities, utilities and transport by then.

Yet we poorly meet even our current needs because we grow the city haphazardly. With insufficient thought about what we should develop where, we don't fully invest in our future. Instead, we meet the likes of our transport and utility needs though disruptive, costly, incremental and insufficient growth.

READ MORE:

* A moment for Auckland

* Urban planning is top priority for ‘reset’

* Why NZ must integrate nature and urban design

Consequently, urban Auckland is a mess. It already stretches more than 60km from Papakura in the south to Long Bay in the north. London, home to five times more people than Auckland, stretches only 50km or so north to south.

Meanwhile, many other cities around the world are evolving rapidly as their residents seek to make them more compatible with climate and nature. One such grouping is C40. Auckland is a member but not an exemplar.

Reimagining Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland was an attempt last year to plot such a necessary and desirable future. But based on where the smartest cities are heading, the report by Sir Peter Gluckman's Koi Tu: The Centre for Informed Futures fell far short, as I described in this column.

Given this background, last week's unveiling of the Southern Auckland Economic Masterplan was billed as a major turning point for the city by Tātaki Auckland Unlimited, the city's economic development agency which had also funded the Gluckman report.

In one sense it was a turning point. It was the first time city and government, plus some developers and businesses, had co-operated on a longer-term vision for part of the city. In this case, the area around Drury, which is largely rural now.

It's taken a while. Work on the masterplan began in 2017 and it's still far from fully developed. But it is so deeply deficient it reads like a lost cause.

Around the world there are myriad examples of other inspiring new urban areas created on abandoned and greenfield land. And we have the expertise to do the same in New Zealand

The report should be based on a thorough analysis of how rapidly technologies, economies and societies are having to change to solve humanity's climate and ecosystem crises.

Instead, it makes a few gestures towards the likes of the circular economy before landing on three sectors it argues will be foundation stones for the southern Auckland economy: food and beverage; construction materials; and health.

Yet, the upside of all three is limited according to the report’s analysis of the state of those sectors here compared with some benchmark countries abroad.

If we matched them, our food and beverage sector would create 1,445 more jobs nationwide and an extra $3.7 billion in GDP; health would create 18,500 jobs and $23.6b; and construction materials 20,900 jobs and $17b.

The masterplan does not estimate southern Auckland's share of those modest upsides. Moreover, other gaping holes riddle the plan.

For example, the report identifies the area's elite soils as a boon to the food and beverage sector. Yet large areas of the masterplan have already been designated for a new town centre, housing and other activities. Property developers have already acquired large land holdings, and in some cases have begun work on them.

Have those designated areas been mapped against soil types good for growing food to show which will be lost to development? Tātaki Auckland said it didn't have such information.

The plan estimates the 2,180ha designated for urban development could be home over the next 30 years to 60,000 people in 22,000 new dwellings, and create 40,000 new jobs

Here's another example of a deep disconnect. The plan identifies the 560ha of land at Glenbrook as a future industrial park, of which some 160ha is used now by the steel mill.

BlueScope, the Australian company that owns the mill and land, says it is "actively exploring technology options to move to low carbon production".

But even if it extends the mill's life, that's no guarantee tenants will be attracted to an industrial park. In its 60-year history the mill has failed to be such a magnet.

One issue is the remote location. The 560ha is surrounded by rural land 27km from SH1 at Drury. Upgrading SH22 to serve an industrial park would be a major investment, which in turn would only exacerbate Auckland's sprawl.

Another major weakness of the masterplan is its lack of detail on housing density. There are only clues such as the visualisation below of what "high density" housing near the new town centre and station would look like.

Very bland, six-storey blocks are the norm. Which is no breakthrough in density or amenities – such low-rise apartment blocks are now being built in many parts of the city.

Of course, detailed urban design comes later in the planning process. But committing now to helping to develop a unique New Zealand style of urban design would lift the new town from generic to distinctive, make it much more liveable and help it attract international investment and renown.

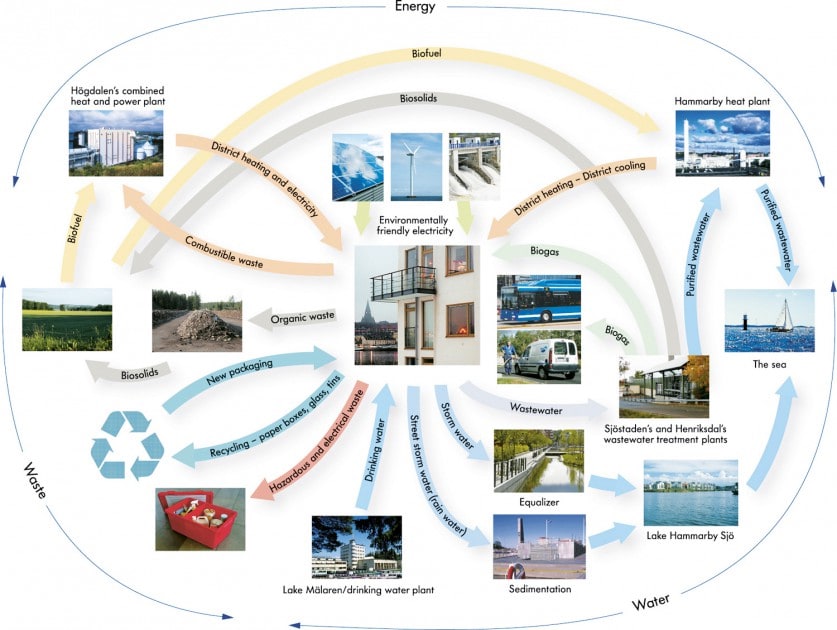

Likewise, it is imperative to embrace now far more sustainable technologies for construction, infrastructure and utilities. The chart below describes those features that helped bring new life to Hammarby Sjöstad, a once-derelict port area in Stockholm's inner city.

Around the world there are myriad examples of other inspiring new urban areas created on abandoned and greenfield land. And we have the expertise to do the same in New Zealand. Whakaora – Our Thriving City is one collective of such people.

But the masterplan for southern Auckland lacks such ambition, insight and creativity. Given its scale, it desperately needs those defining attributes.

The plan estimates the 2,180ha designated for urban development could be home over the next 30 years to 60,000 people in 22,000 new dwellings, and create 40,000 new jobs.

But over the same few decades we'll need the equivalent of another dozen or so such greenfield new builds or brownfield redevelopments to meet the needs of the city's growing population.

So, let's learn very fast how to do this. Then Auckland will gain a global reputation as a highly liveable, deeply sustainable, culturally vibrant, socially cohesive, and economically bountiful city.