Valve's Steam Deck has done more for the world of handheld PC gaming than perhaps any other device in history. Reports indicate that the Steam Deck could sell over 3 million units before the end of 2023, and many games have started to add "Steam Deck" settings options to make them run better on the low-power hardware.

All three models of the Steam Deck that Valve sells have similar core features. The only real change is in the storage capacity, as well as the display coating — the most expensive model comes with an anti-glare screen — and a few potential extras in the way of Steam profile options.

The base model comes with a 64GB eMMC storage drive, which uses an mSATA interface. It costs $399, and the upgraded 256GB model, with a full PCIe 3.0 x4 interface, tacks on $130 to the price and sells for $529. Finally, the top model comes with a 512GB SSD and the premium display, for another $120 on top of the middle tier — $649 total.

We don't know precisely how much of the cost is related to the display, but it's likely not more than about $25 in raw costs. Any way you slice it, that's a big upcharge for what still amounts to a relatively pathetic amount of storage — plenty of modern games will happily swallow 50GB or more of your storage, with a growing number passing the 100GB mark.

Perhaps more importantly, SSDs are damn cheap right now. For standard PCs, you can pick up 2TB of capacity for under $100. Of course, that's using the minimum spec devices that aren't likely to perform as well, but even high-performance PCIe 4.0 x4 drives like the WD Black SN850X 2TB start at just $100.

But M.2 2230 SSDs are a different story. Prices aren't terrible, but the 1TB drives start at around $100, while the 2TB drives can cost $200 or more. That's above pricing for standard SSDs. Still, that's far better than what Valve charges, and anyone who knows how to use a screwdriver shouldn't even consider paying extra for a Valve-certified SSD, not when you can get larger and faster drives for less. The only reason to get the 512GB model from Valve is for the premium display, which is a steep price to pay if you're just going to replace the provided storage with something more spacious.

Upgrading the Steam Deck SSD

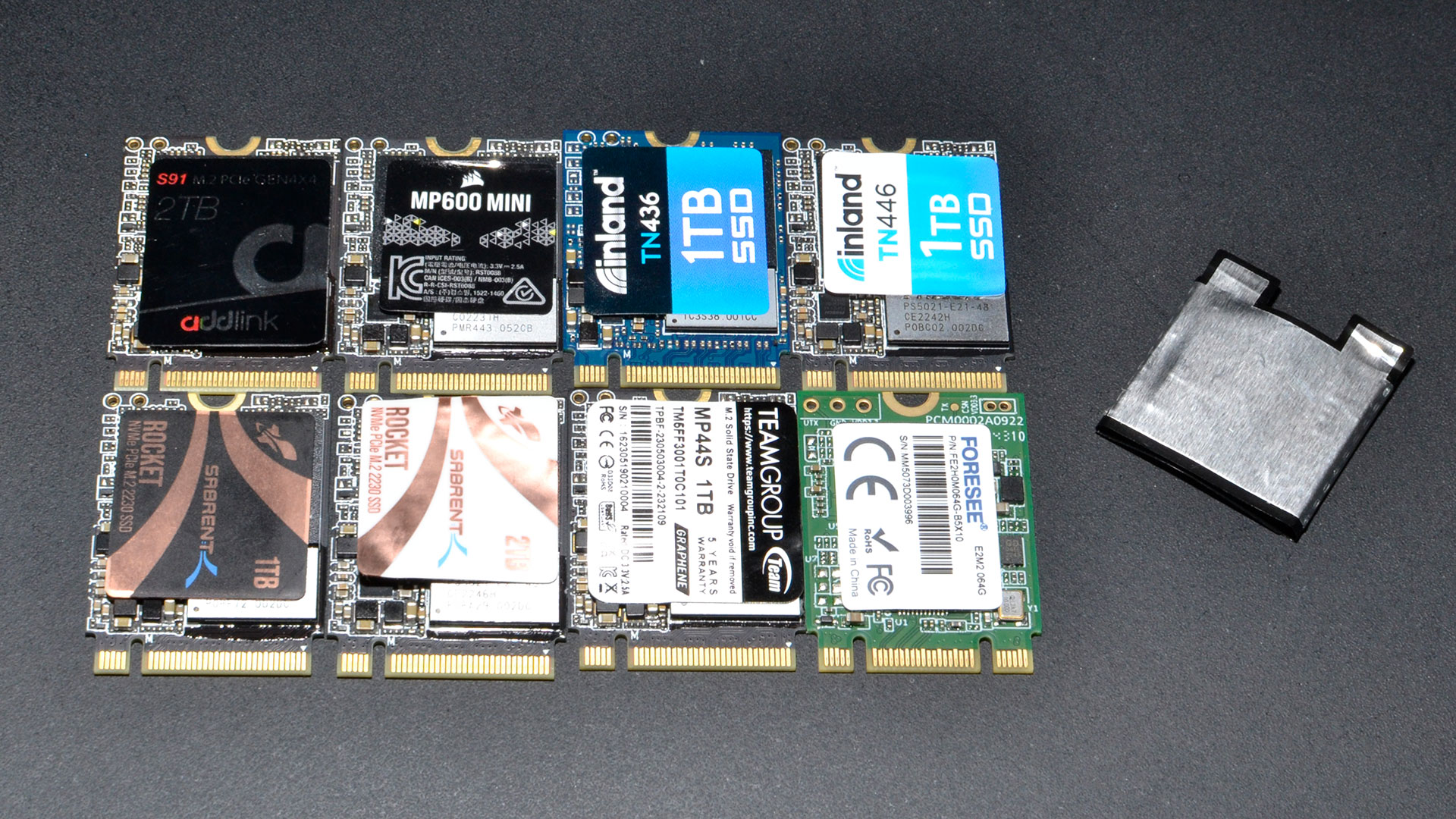

Given the prices, we won't bother with the upgraded Steam Deck models. We purchased the base 64GB model during the most recent Steam sale for $330, and promptly set about testing all of the M.2 2230 SSDs we currently have in our possession on the device. It's surprisingly easy to do the upgrade, but we've got pictures in the above gallery for those that want a brief overview.

First, you should shut down the Steam Deck — you don't want it in sleep mode when you swap out the storage device. Some say you should disconnect the battery when swapping out the SSD, but honestly, we skipped that step. We left the battery connected during all of our SSD swaps, though we did take care not to accidentally power up the Deck while working.

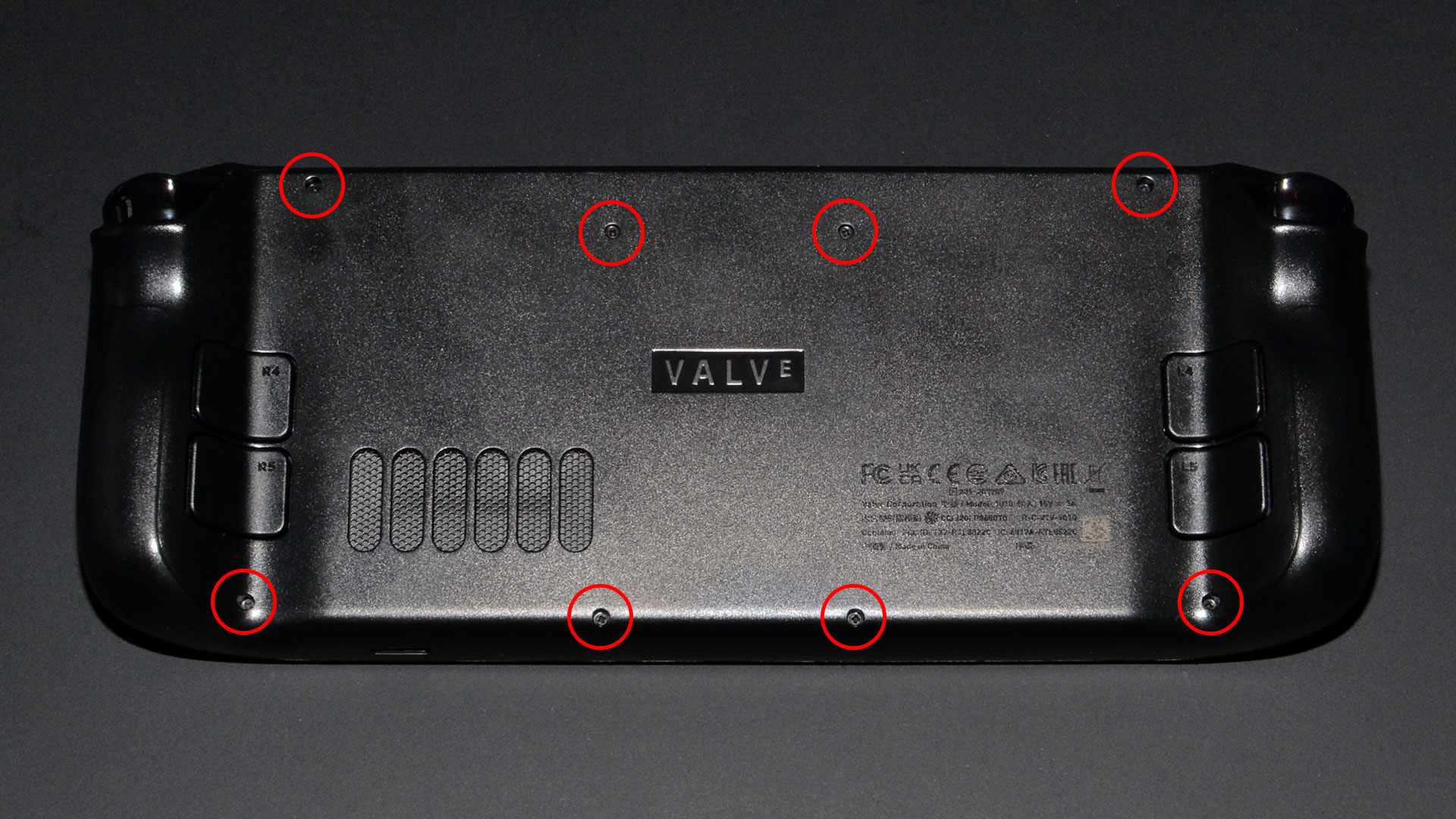

Compared to some devices, accessing the Steam Deck internals is simplicity itself. There are eight small Phillips screws on the bottom of the Deck, and once those are removed, all you need is a thin plastic wedge to pry the system open. Once inside, you could replace the paddles and thumbsticks should they wear out. We're only interested in the storage, so we'll focus on that.

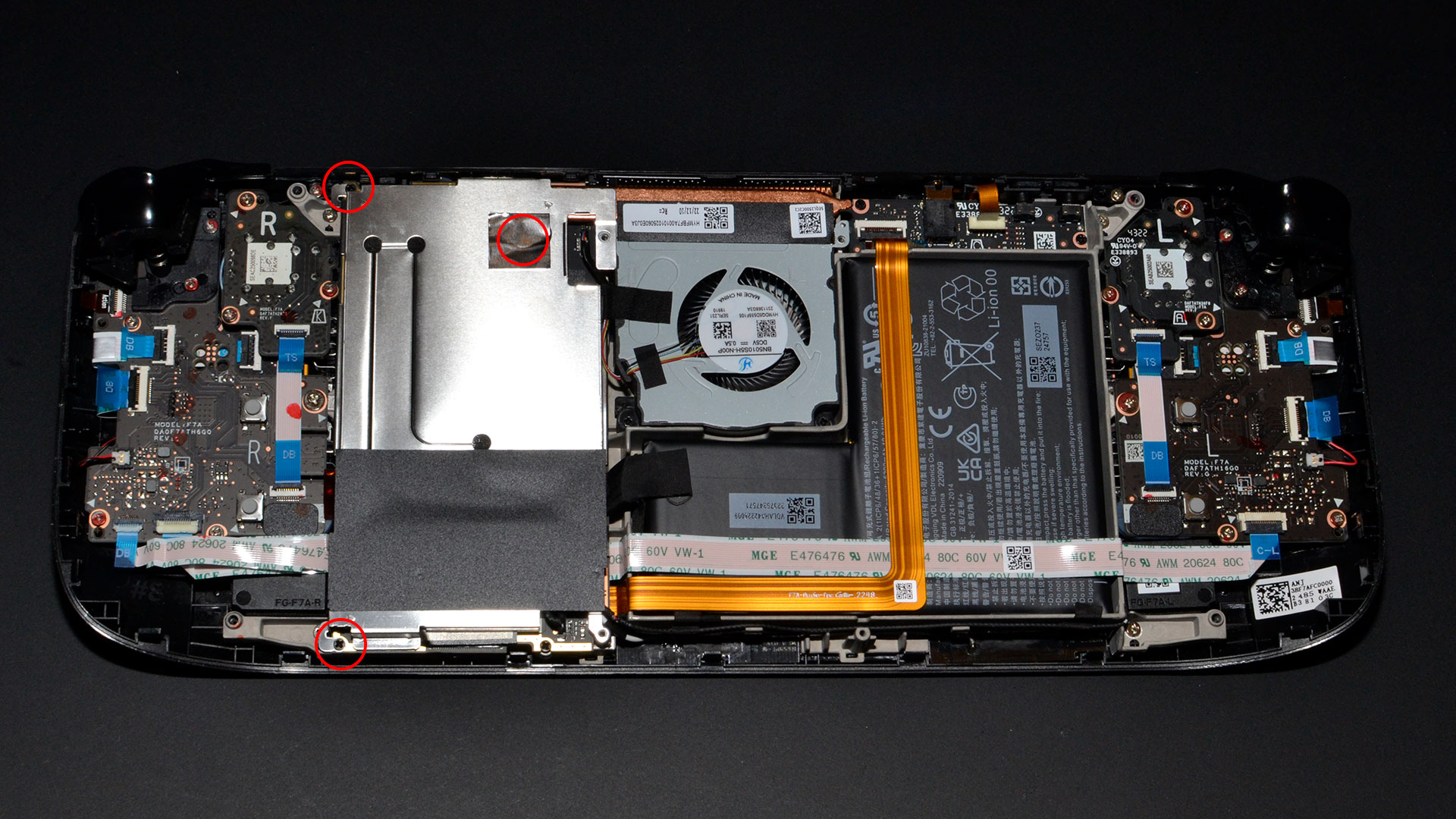

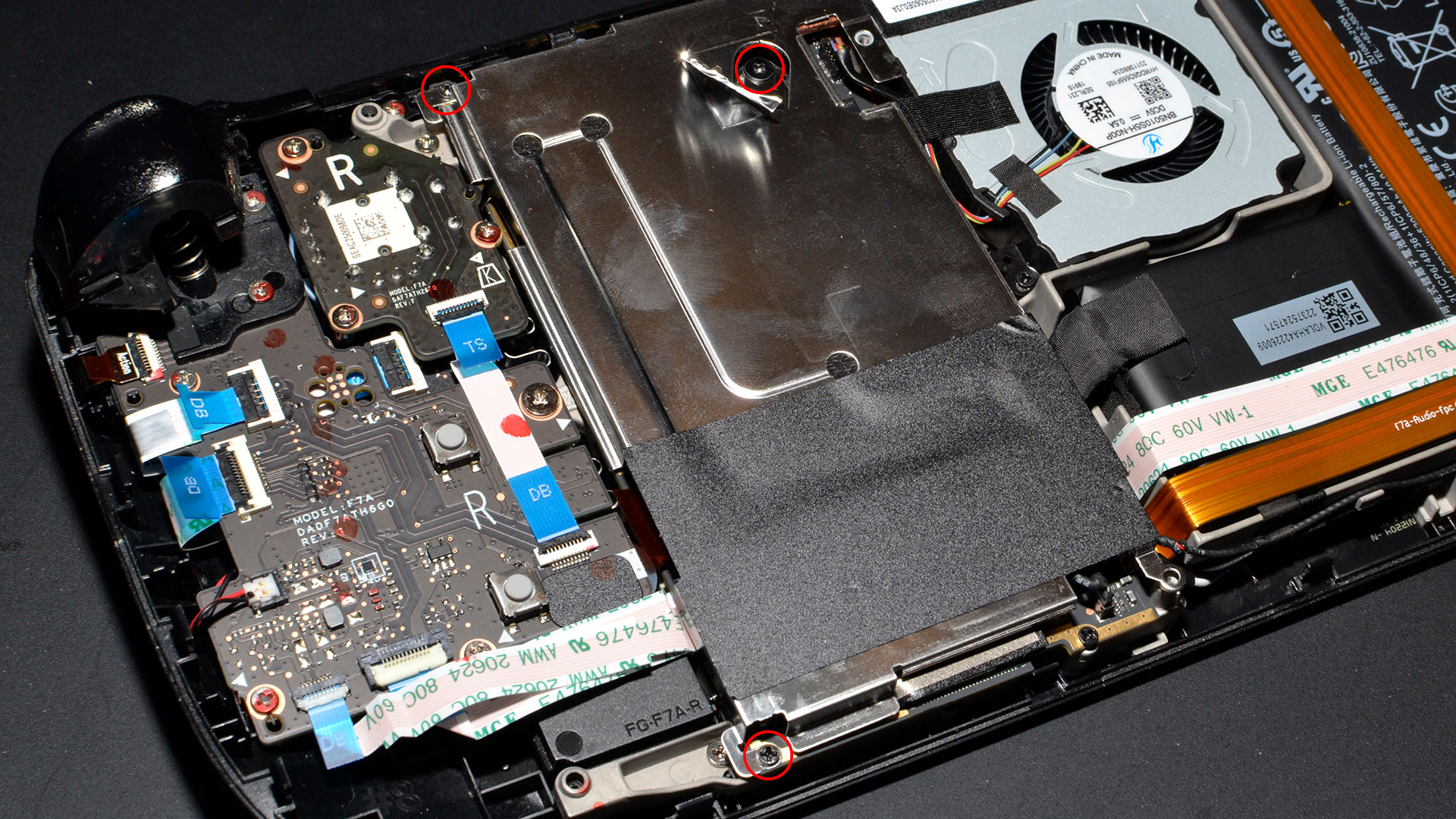

An aluminum EMI shield covers the SSD slot, secured by three more Phillips screws. One of the screws is hidden beneath some metallic tap, so peel that back but keep it because you don't want to potentially interfere with the WiFi reception. Some slightly sticky thermal pads hold the metal shield in place, so after you've removed the screws, you'll need to lift the shield carefully.

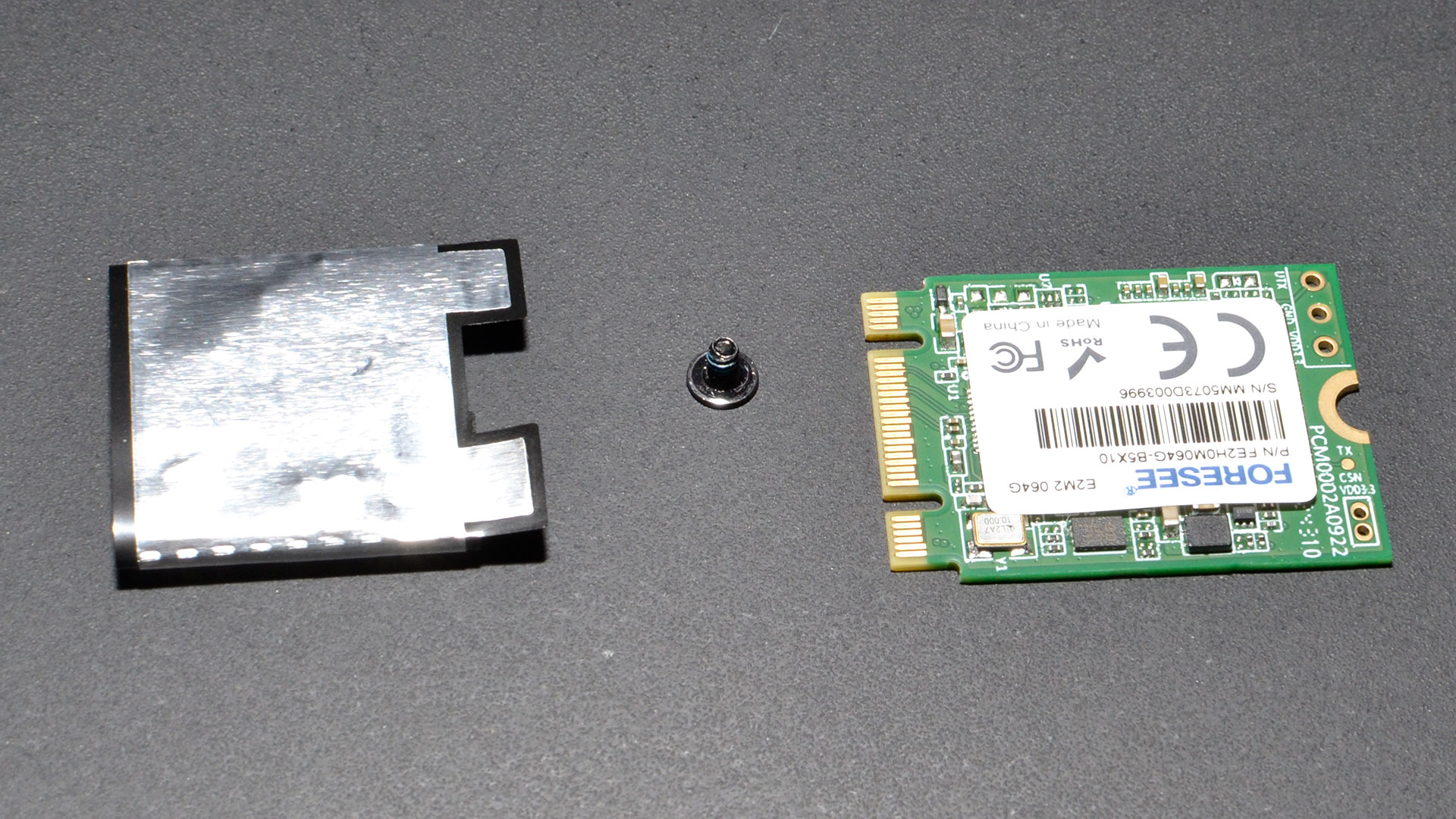

And that's all you need to do to get to the M.2 2230 slot. You can see that the original Valve SSD comes with yet another EMI shield around it, and it's secured by one final Phillips screw. Take out the old SSD, slide off the foil wrap, and then put it around your new SSD. Now reverse the process, and you're ready to reinstall SteamOS.

Valve has a helpful support page detailing how to reinstall SteamOS on the Steam Deck. Download the drive image, then use Rufus USB to create a bootable USB device. Note that you'll need a USB Type-C stick or an adapter — we used a spare Samsung T7 Touch 1TB SSD that we had lying around, but there are far cheaper options like this SanDisk 32GB stick.

Plug the newly imaged device into the Deck, hold down the volume down button, press and release the power button, then release the volume button after you hear the power on sound. Boot off the USB device, and in a minute or so, you'll be greeted with the Linux interface. Since the SSD is blank, click the "Re-image Steam Deck" icon on the desktop, and after a minute and a couple of button clicks, the Steam Deck will boot to the SteamOS welcome screen.

Testing the Steam Deck Storage

We'll be including Steam Deck performance results in all our future M.2 2230 SSD reviews, as this is one primary use case for such drives. Those reviews will have our full suite of Windows SSD performance testing as well, including additional tests with the drives in PCIe 3.0 mode (if they're PCIe 4.0 drives, which applies to all the drives we've tested) because that's the speed of the internal bus on the Steam Deck. But using the Steam Deck tends to be a far less demanding scenario, plus it's running Linux, so we wanted to run some Deck-specific benchmarks.

First, because we knew the SteamOS installation would hit the storage relatively hard (compared to other tasks), we timed how long it took to re-image SteamOS, plus the subsequent restart and boot to the welcome screen. We then timed the full SteamOS setup that takes place after you connect to a wireless network — the longest part of the installation process. We also timed the initial OS update that's available (as of July 10), and after everything was up to date, we timed the standard boot sequence for SteamOS.

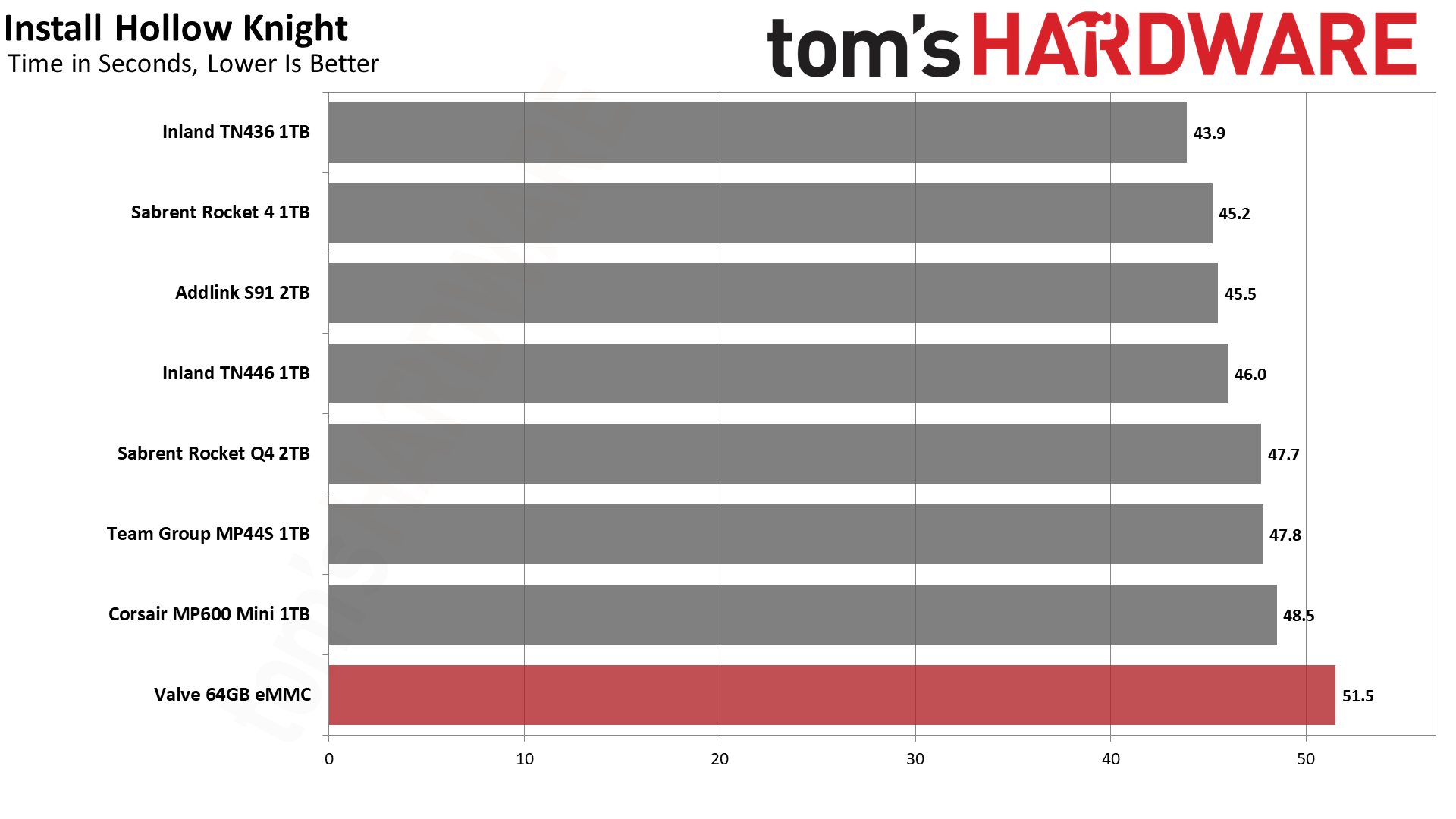

Besides the OS testing, we wanted to check how long it took to install a game. Because we want to compare the performance of the upgraded SSDs with the base model 64GB eMMC drive, that somewhat limits what we can do. For example, installing any game larger than 45GB isn't possible on the eMMC drive. We opted for installing Hollow Knight, a 2D platformer that runs nicely on the Deck.

Steam will also install Proton 7.0 and some other software the first time you install the game, but we didn't include that time in our testing. We uninstalled and reinstalled Hollow Knight a few times on each SSD, just to check for consistency of results, which we'll discuss more below.

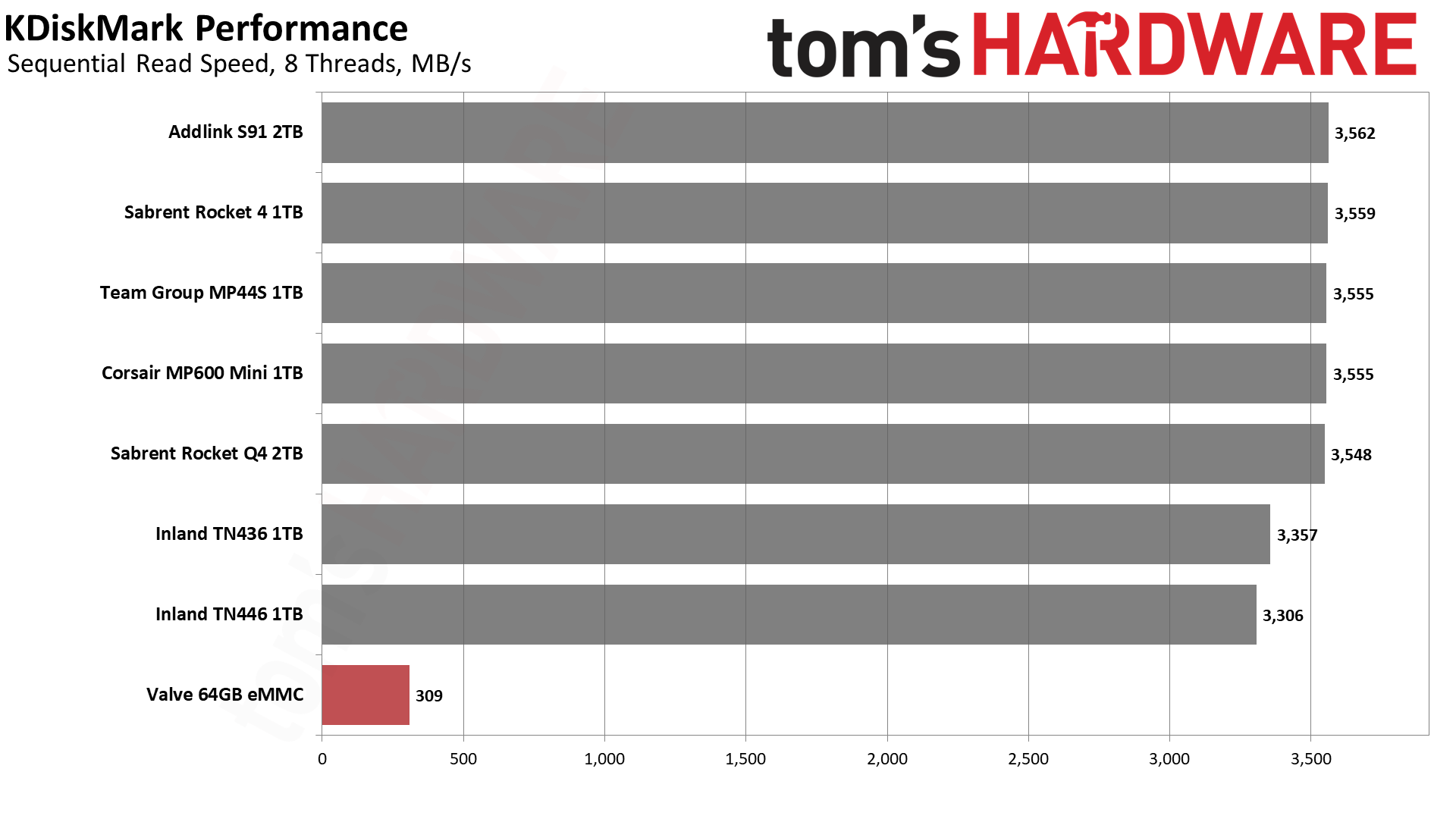

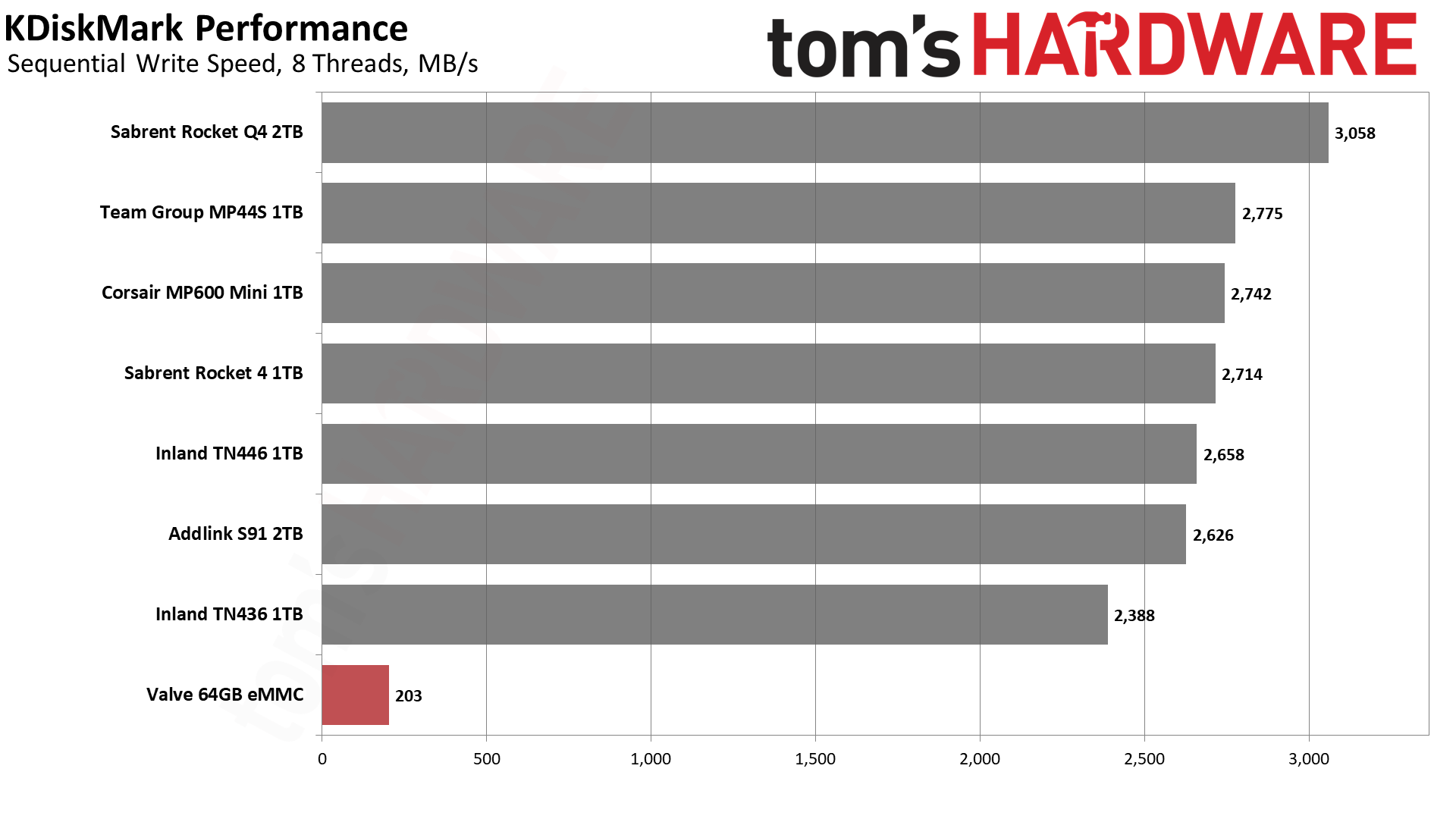

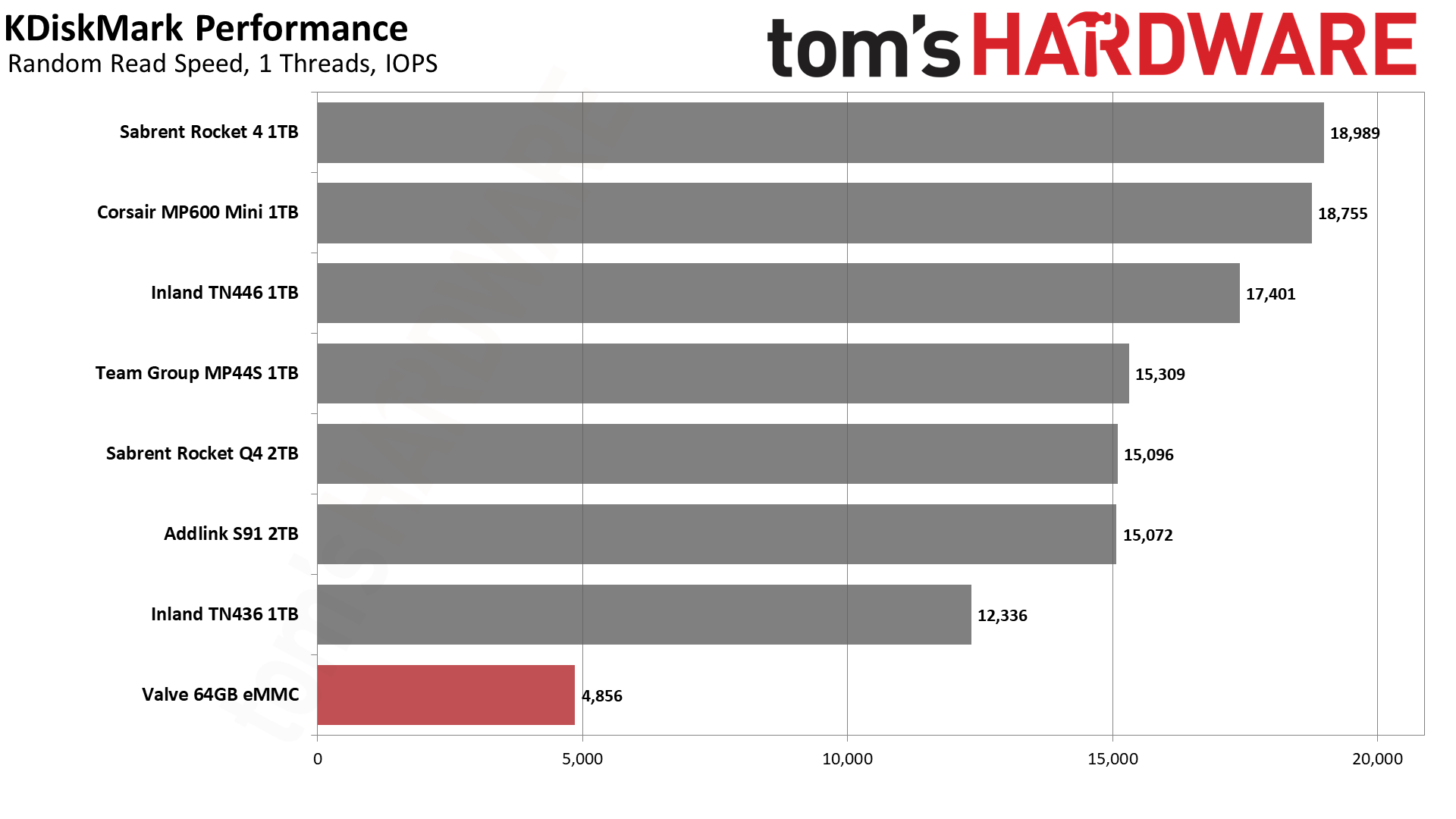

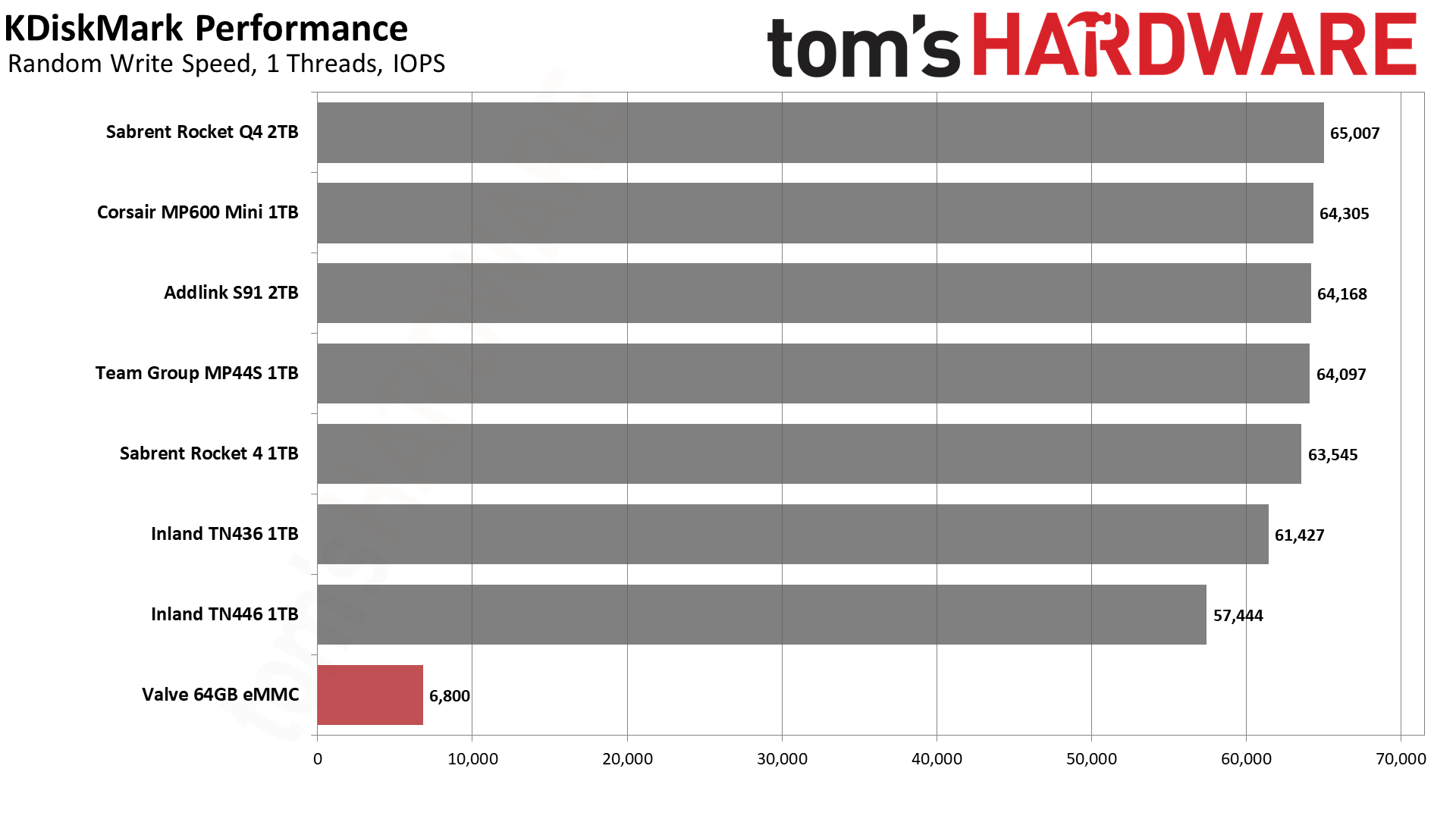

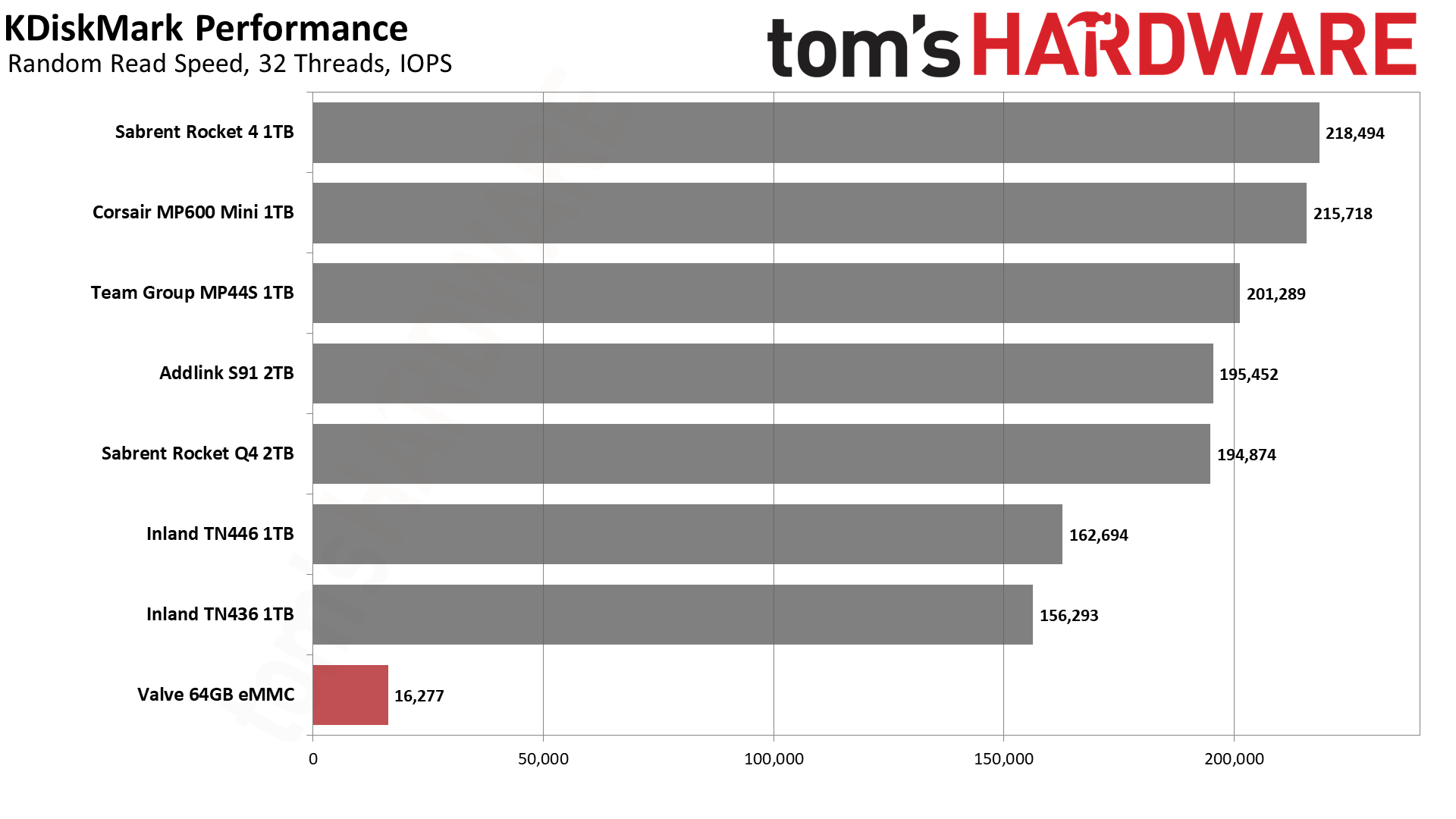

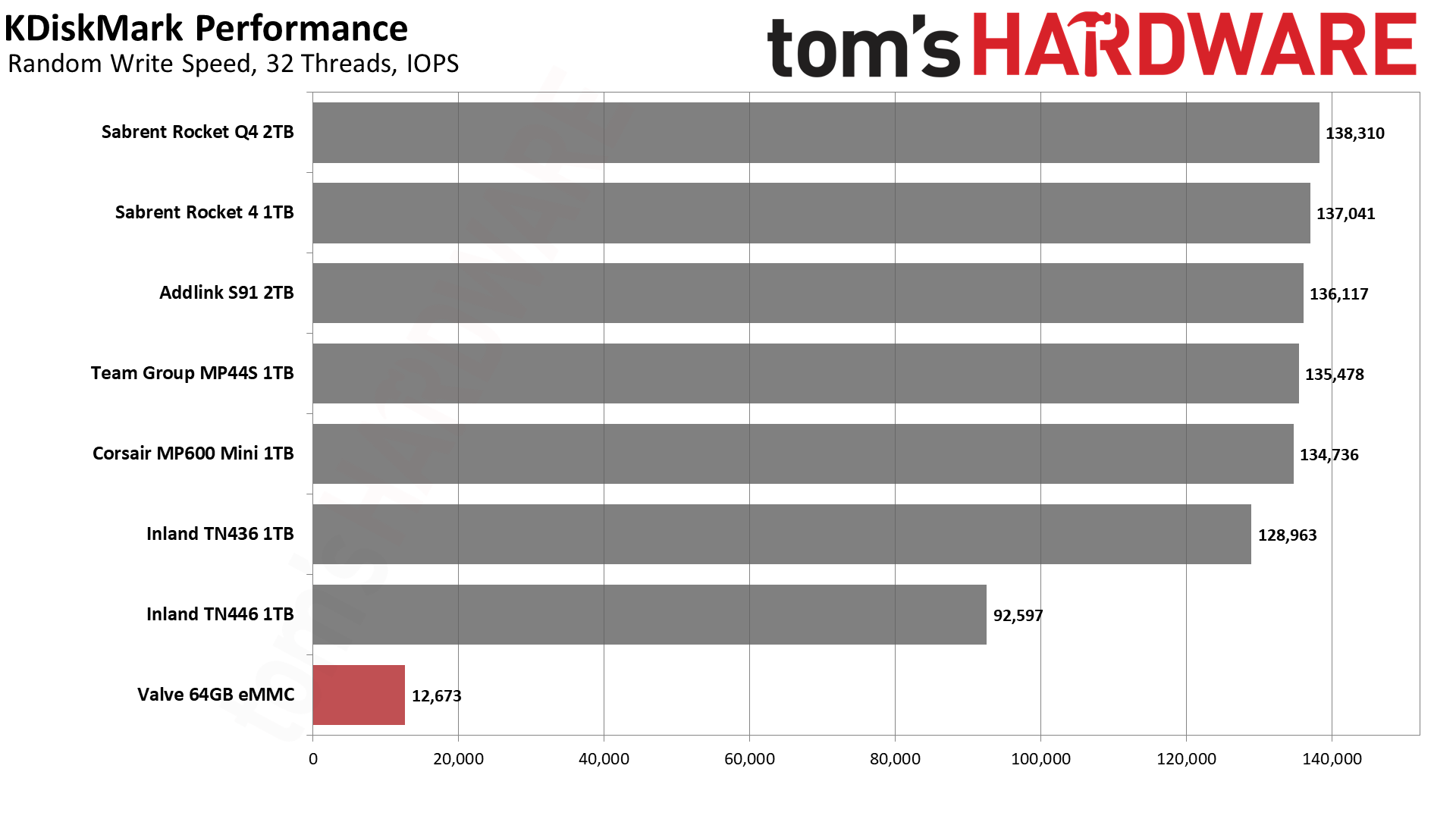

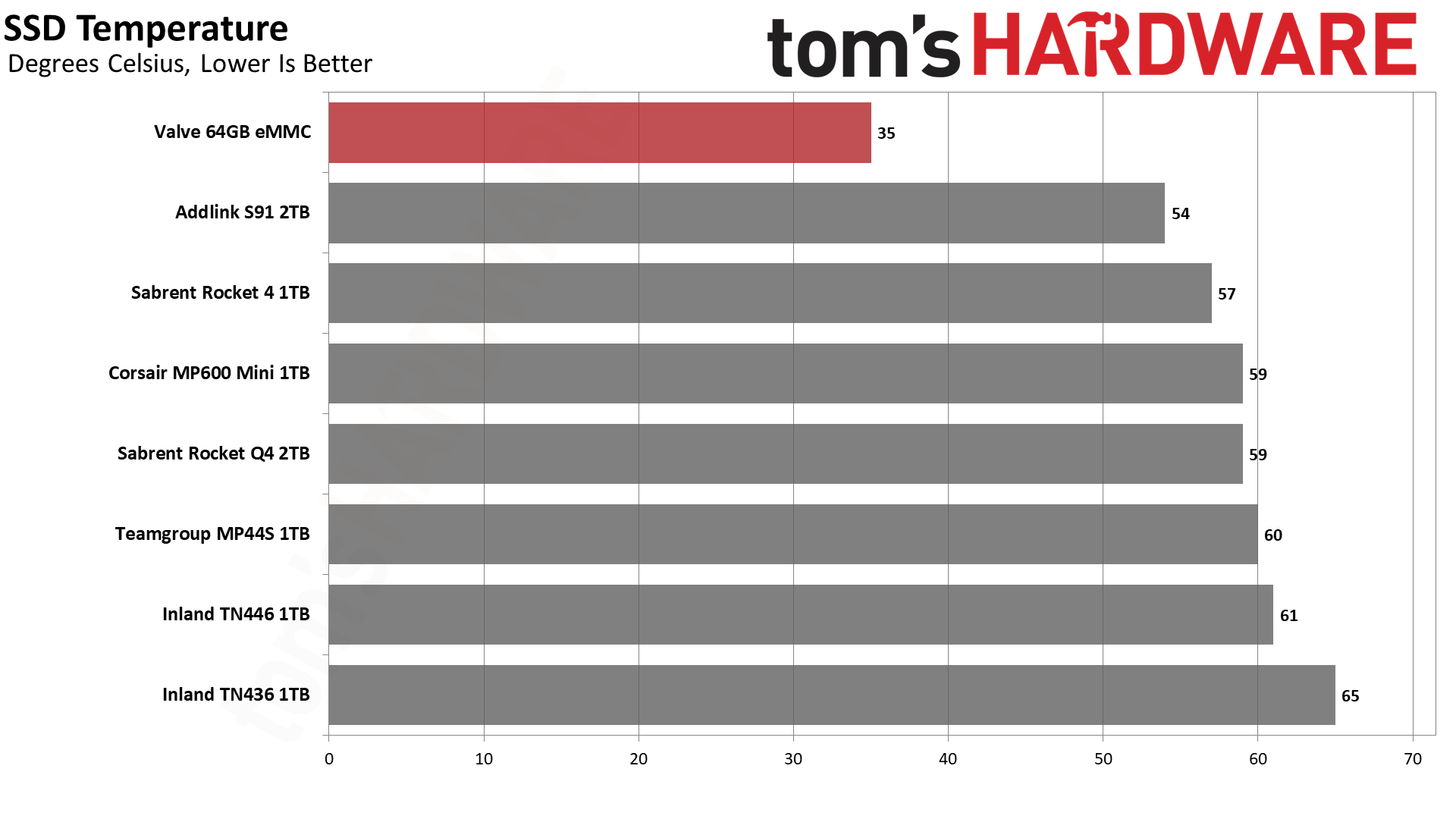

Finally, we ran a synthetic SSD performance test, KDiskMark. We used the default 1GB test size and gathered the sequential and random read/write speeds. We ran KDiskMark at least three times, keeping the best results. Note that these figures are more theoretical and likely don't reflect how the storage speed will impact your daily use of the Steam Deck, since most tasks are not purely storage limited. We also gathered SSD temperatures while running KDiskMark to see how hot the drives get. We're also working on battery life benchmarks, which remain a work in progress.

Steam Deck Benchmarks: eMMC vs. Upgrade SSD

Here are the results of our initial performance testing of the various SSDs, compared with the base 64GB eMMC drive. Our base drive was a Foresee FE2H0M064G-B5X10, though it appears different parts may be used depending on when you purchase the Steam Deck. We're testing with the recovery image from July 7 (steamdeck-recovery-4.img.bz2). A few anomalies during testing warrant mention, as Linux support for the various SSD controllers tends to be a bit variable.

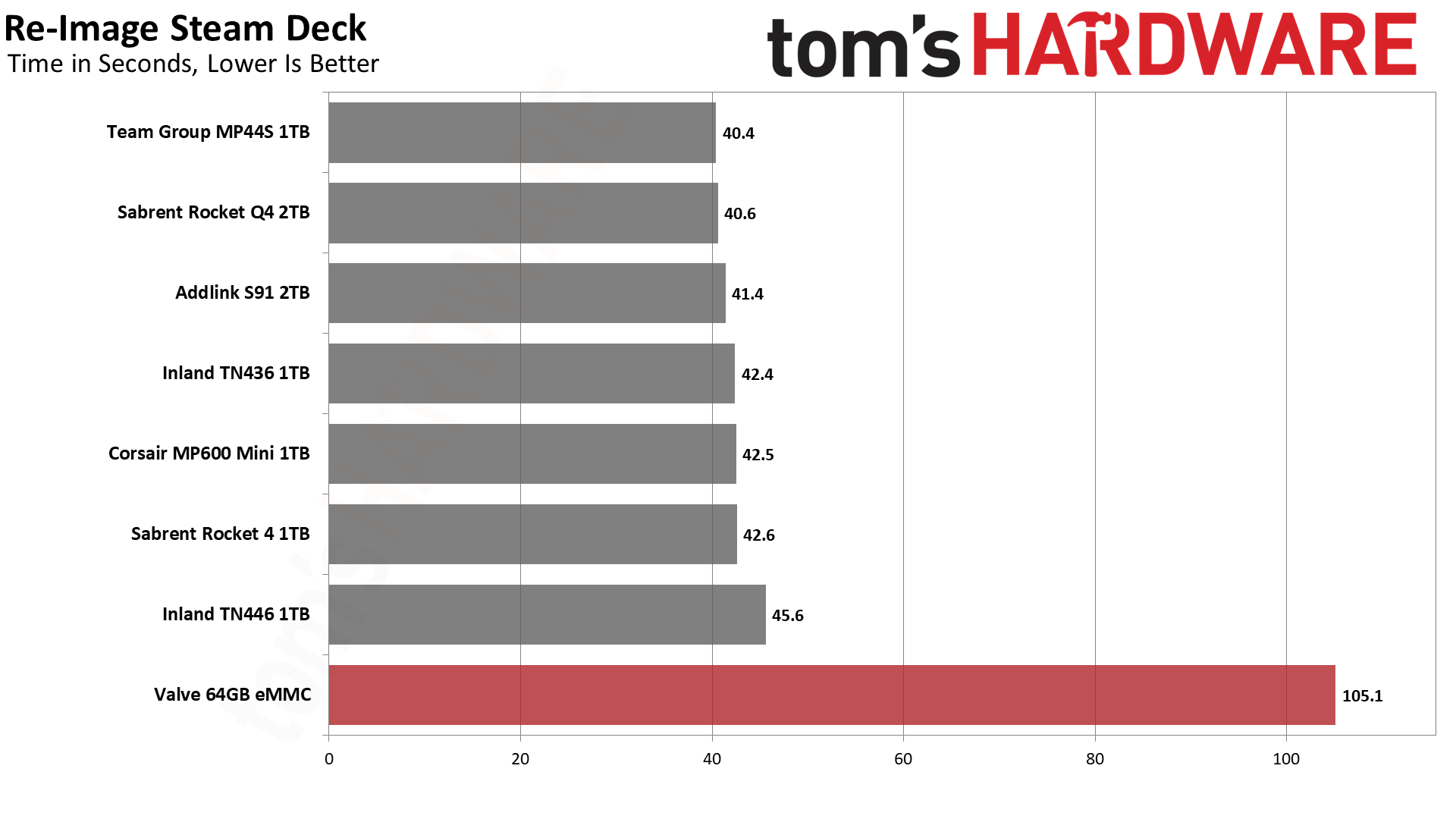

This is probably the biggest difference you'll see (other than capacity) between the base eMMC drive and an upgraded SSD. The eMMC drive uses an M.2 SATA connection. The interface offers a peak theoretical bandwidth of 6 GT/s (600 MB/s), which is still more than the eMMC drive can manage — it peaks at around 300 MB/s, as we'll see below. Writing the 10GB or so of OS data to the eMMC takes twice as long as the other SSDs.

Besides that major difference, most of the drives land in a relatively narrow range. The fastest drives are the Team Group MP44S, Sabrent Rocket Q4, and Addlink S91. The Inland TN446 ended up being the slowest SSD by three seconds, though that's likely due to Linux support for the controller.

One oddity was that several drives — the Corsair MP600 Mini, Inland TN436, Inland TN446, and Sabrent Rocket 4 — would stall out for about 60 seconds at one of the "creating journal" steps. This step normally just flashes past in a split second, but on those four SSDs, it seemed to get stuck. We did not include that additional time, as we figure it will be fixed at some point with future Linux kernel updates.

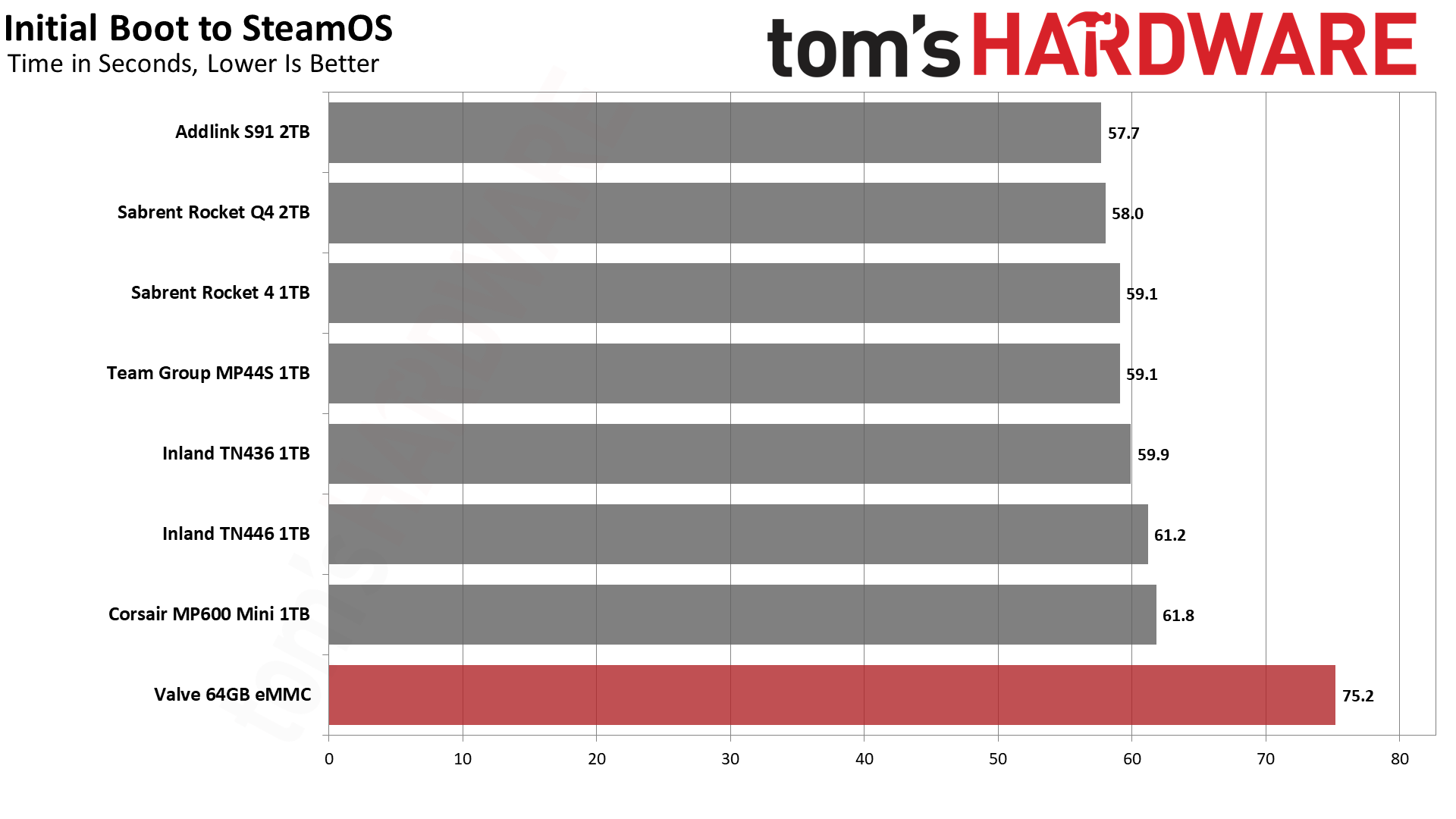

After re-imaging, the Steam Deck reboots and eventually loads to the welcome screen, where you're asked to select a language. We timed the entire restart plus boot process, and all of the SSDs again performed pretty similarly, with the eMMC drive taking about 15 seconds longer. Unlike the re-imaging process, there were no odd stalls on any of the SSDs.

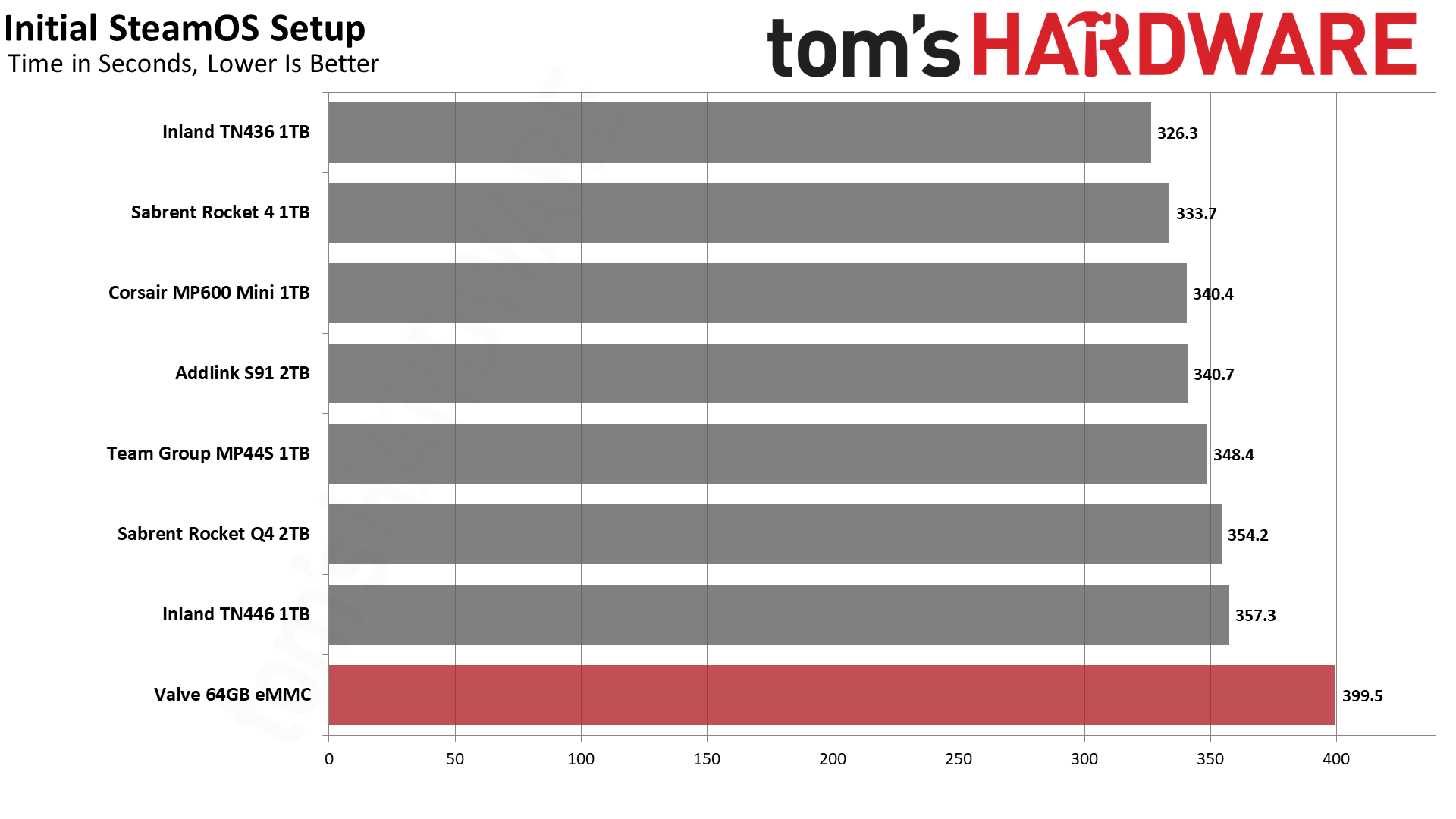

This is by far the most time-consuming task, the initial SteamOS setup. After you choose a language and connect to a network, there's a lengthy install process for the OS. Presumably, it's unpacking files and getting the software ready.

The time required doesn't necessarily correlate directly with the expected SSD speed. For example, the TN436 performs quite a bit worse than the TN446 in our Windows tests, at least on sustained writes. That's because it uses an older Phison E19T controller, while the TN446 uses the newer Phison E21. However, Linux may have better drivers for the E19T right now.

It's also possible that there's more variation between runs on this step. As with the re-image, several of the drives got to a point where they would stall out at a screen saying, "Starting Steam Deck update download..." We waited over ten minutes on one of those drives before giving up, returning to the previous step, and trying again. (The Addlink, Corsair, Sabrent Q4, and Teamgroup drives all experienced the same behavior.)

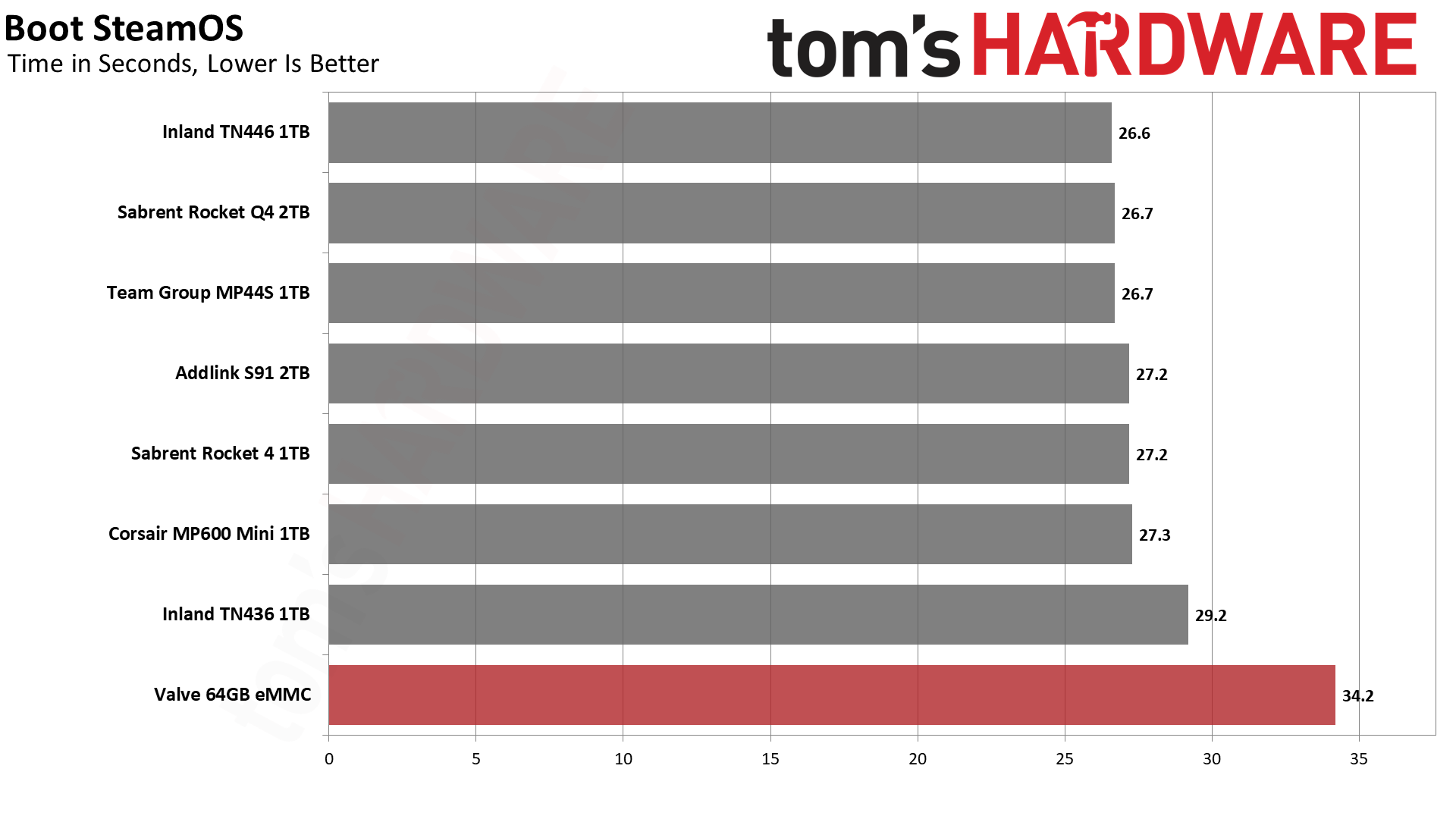

More useful than the first metrics, this is the standard time required to boot the Steam Deck from a power-off state. We check that the OS is fully up to date before timing the boot process, so this is what you should normally experience. We also measured the first OS update, which took about 35 to 37 seconds on the SSDs, and 44 seconds on the eMMC drive.

Installing a game was another step that proved quite variable among the drives. The Steam Deck only has wireless networking support, and the Steam servers can also experience different loads. We uninstalled and reinstalled Hollow Knight multiple times to get a good feel for each SSD, selecting the best result that was regularly attainable.

For this test, we were sitting about ten feet from our Wi-Fi 6 capable router, and the Steam Deck reported peak bandwidth use of just 300–320 Mbps. The router is capable of 866 Mbps, though you don't see the full bandwidth due to interference. Again, one of the "slowest" drives in our Windows benchmarks ended up as the fastest in this test: The Inland TN436 outpaced its newer sibling.

One thing that isn't clear is whether the faster SSDs might be causing some slight interference with the Wi-Fi signal (EMI). It still worked with every SSD we tested, but several SSDs with the Phison E21 controller (Corsair, Teamgroup, and Inland TN446) performed a bit worse here.

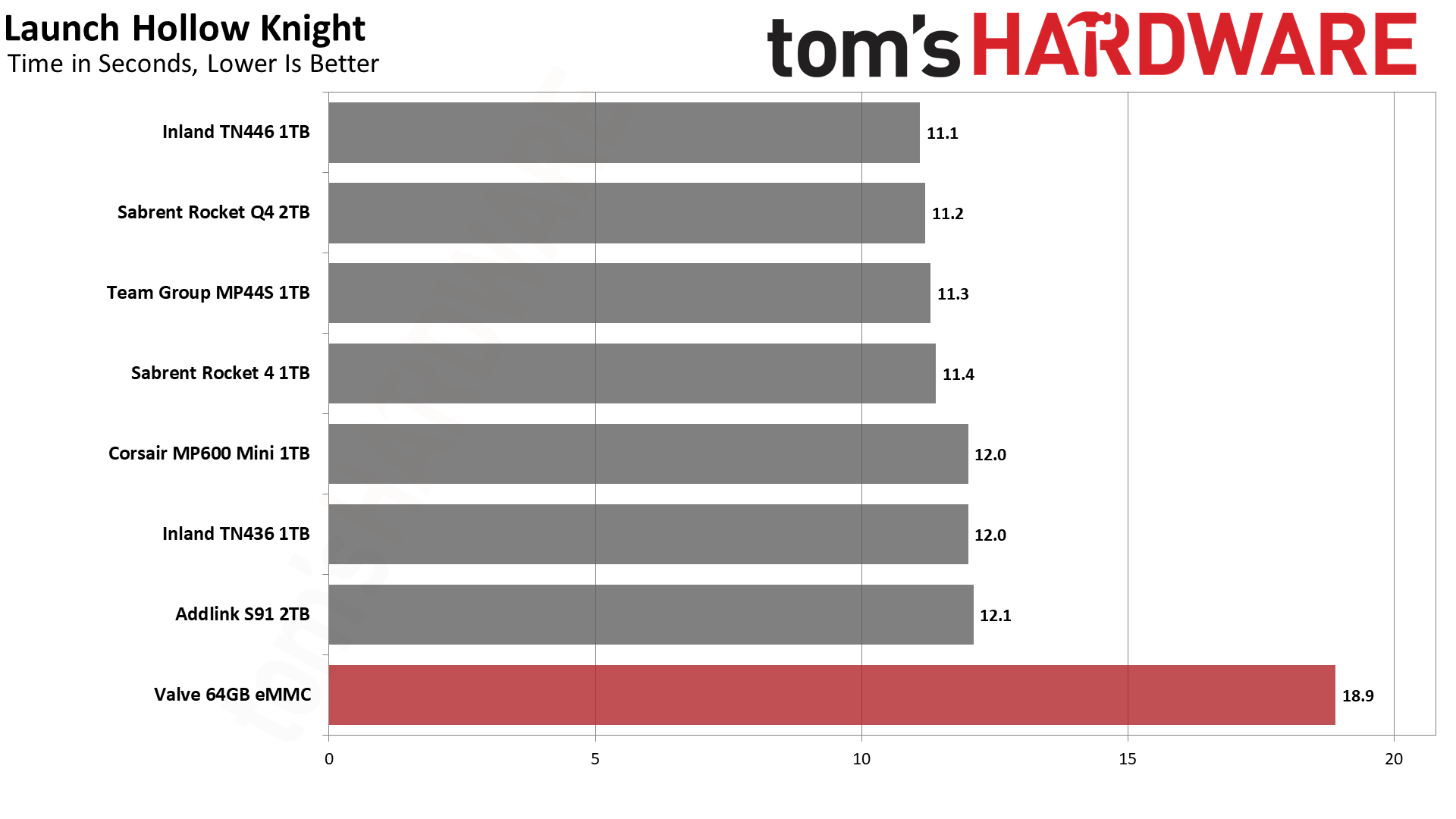

This is the time required to launch Hollow Knight, after rebooting the Steam Deck. (It doesn't take as long if you've previously launched the game, even on the eMMC drive, probably due to OS caching.) There's only a one-second difference between the fastest and slowest SSD, but the eMMC drive takes 7–8 seconds longer.

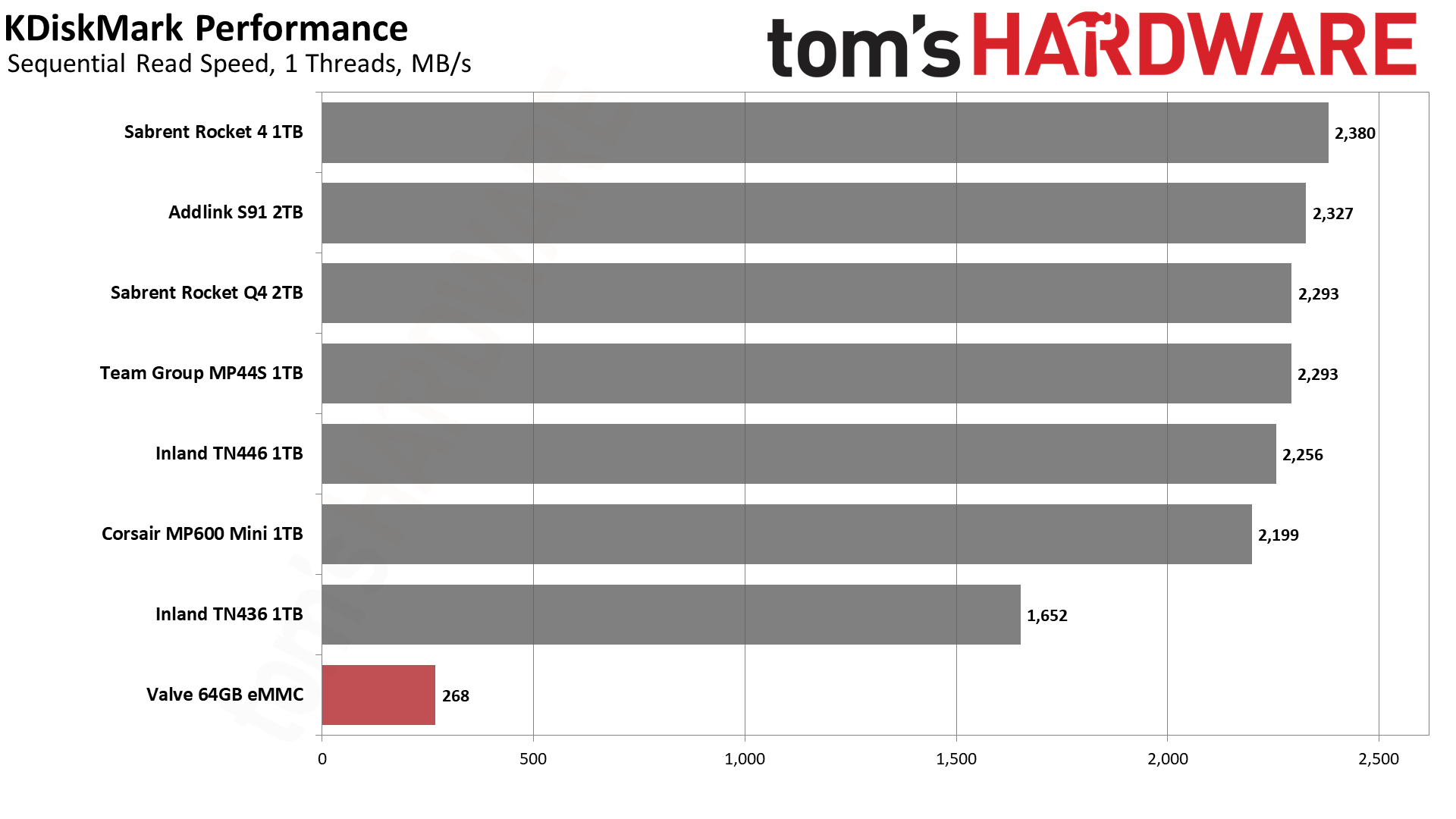

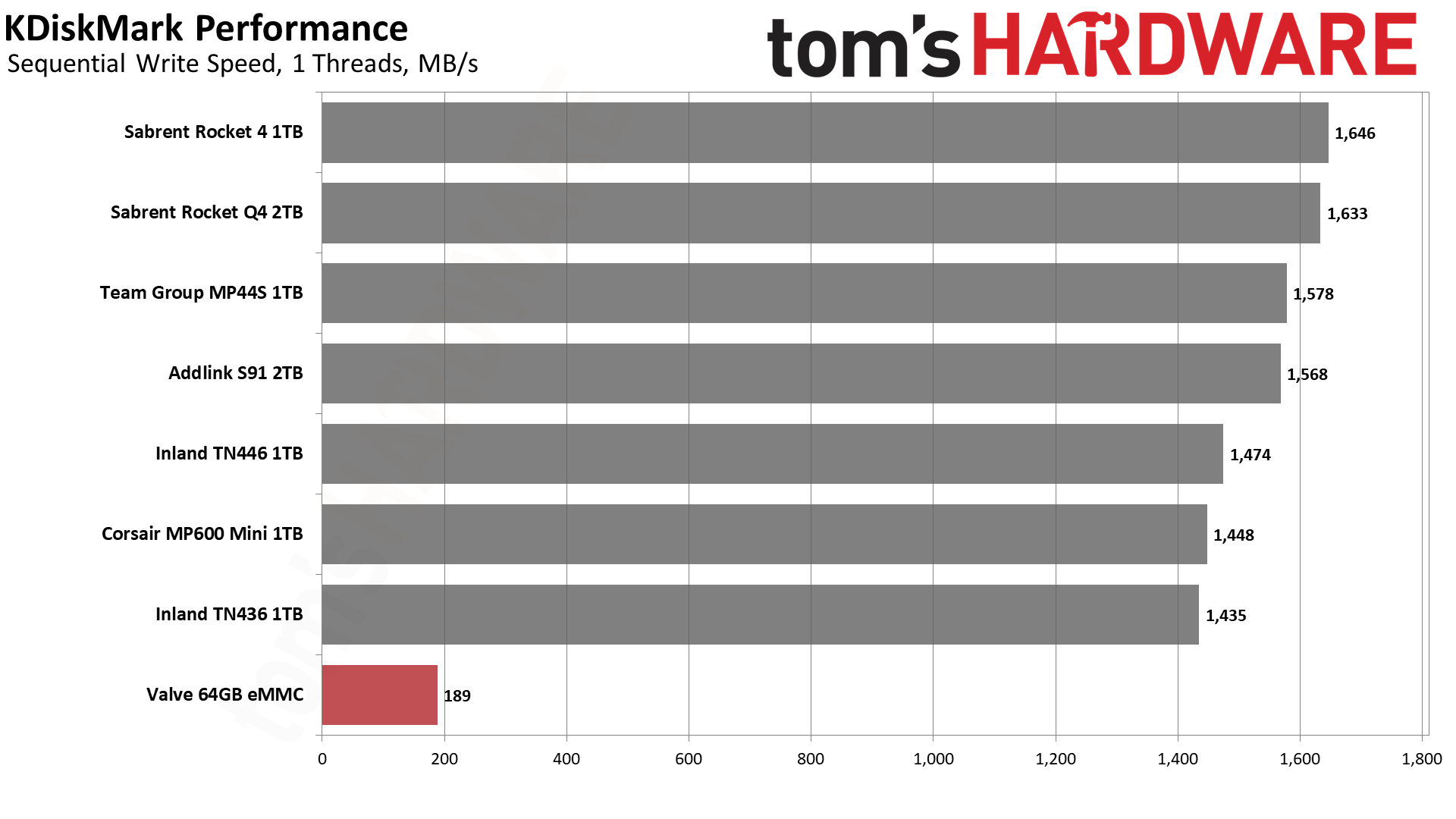

KDiskMark is basically a Linux variant of CrystalDiskMark. It runs various sequential and random IO workloads, doing the read testing first and then the write testing. Note that performance at higher queue depths (Q8, or eight threads) tends to be less real-world and more of a theoretical storage benchmark. That goes double for the 32-thread random testing. We put far more weight on the single-thread results, which correlate better with the actual game load times and OS updates.

The eMMC drive looks very pathetic in these synthetic storage benchmarks, managing just 268 MB/s of read performance and 189 MB/s of write performance with a single thread. The random IOPS with a single thread also falls well behind the other SSDs.

If you were doing a lot of storage-heavy IO, these results might be more pertinent, but for the Steam Deck, you'll mostly be loading or installing games or occasionally booting the OS. Since game downloads happen over the wireless connection, you're effectively capped at around 30–40 MB/s of write performance, which even the eMMC drive can manage.

Last but not least, we have the SSD drive temperatures, as reported by smartctl. We suspect the eMMC drive isn't actually reporting the correct data, as its temperature was always listed as 35C. Nearly all other devices would start at around 44–51 degrees Celsius and then slowly heat up while running KDiskMark, which is what you'd expect.

One interesting point the peak temperature doesn't convey is the idle/start temperature. As noted, every SSD was in the 44C to 51C range at idle, except for the Inland TN446, which idled at 55C. It didn't heat up as much as the TN436 under load, but it doesn't seem to be properly entering a low power state. That could definitely impact battery life.

All of these SSDs are rated for temperatures of up to 80C or 85C, and they're nowhere near that level. Under normal use, the APU will generate far more heat than the SSD controller, which is what will actually cause the Steam Deck to warm up.

Still, if an SSD idles at 1W instead of 0.3W, that will reduce battery life. Unfortunately, we don't have tools to measure the idle power for these SSDs while in the Steam Deck. However, you can refer to the drive reviews to see what power use was like under Windows — they'll be published over the course of this coming week.

Closing Thoughts

Given how cheap "normal" M.2 SSDs are these days, doing an inexpensive storage upgrade for the Steam Deck is an enticing prospect. However, the 2TB drives in the 2230 form factor cost substantially more than the 1TB models, so 1TB is probably the sweet spot for most people. That's enough for a dozen or more moderately large games, or a whole bunch of smaller and less demanding games — which are often a great match for the Steam Deck.

We should see prices drop over time, as several other devices, including the Asus Ally, also use M.2 2230 drives. There are quite a few older PCIe 3.0 2230 drives as well, but as we're just getting started with our 2230 testing, all of the devices we've received for review are newer models with PCIe 4.0 support — even though the Steam Deck is limited to PCIe 3.0.

We will look at testing additional 2230 drives on the Steam Deck as new models become available. We may also revisit this topic with some of the more popular older 2230 drives if companies want to send us review samples.

Our experience with upgrading the Steam Deck storage was relatively simple and painless. Valve cautioned against end-user SSD mods with 2242 SSDs, but plenty of 2230 drives are available and don't require any modifications. If you're reasonably competent, upgrading to a larger 2230 SSD shouldn't be a problem. Depending on the drive, battery life might be slightly diminished, but 2230 SSDs aren't generally high-performance, high-heat devices — unlike the latest 2280 PCIe 5.0 drives.

We have multiple separate reviews for each of these drives that we'll post over the coming week or so. We'll suss out the best and worst of the drives based on the more expansive set of results in the full test suite, as well as their pricing. Look to these pages for those reviews soon.