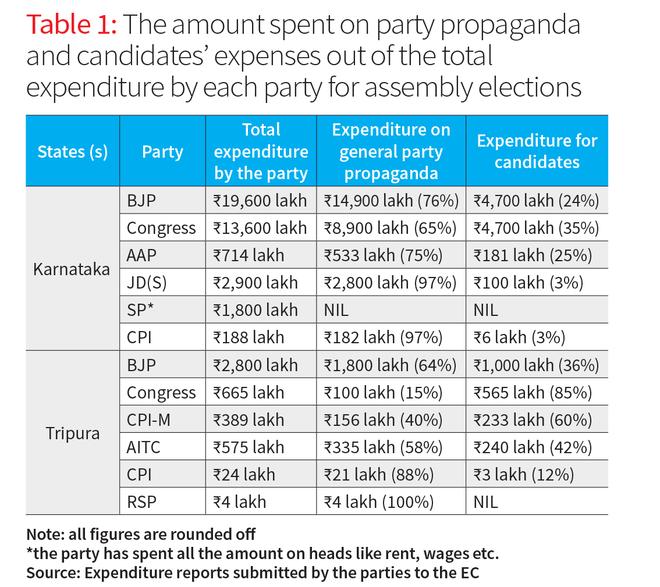

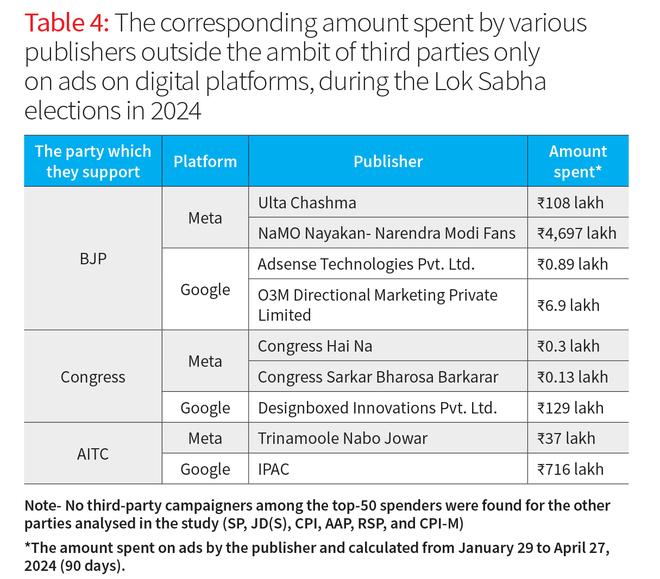

In the colourful mosaic of Indian democracy lies a fundamental question that strikes at the core of our democratic ethos: the issue of electoral expenditure. In the 2019 general elections alone, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress collectively spent an astronomical sum of over ₹20 billion. While the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA) meticulously outlines expenditure limits for individual candidates, a glaring gap remains — the absence of comparable restrictions on political party spending (Table 1) and third-party spenders/campaigners (Table 4). This discrepancy has not only opened the floodgates for unchecked expenditure by parties but has also paved the way for a skewed electoral landscape, where financial muscle trumps meritocracy.

The researchers of CSDS-Lokniti analysed the expenditure reports submitted by various political parties during the Karnataka and Tripura State Assembly elections in 2023. In Karnataka, the study scrutinised the spending of three national parties, the BJP, the Congress, and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), alongside three State parties which are the Janata Dal (Secular) (JD(S)), the Samajwadi Party (SP), and the Communist Party of India (CPI). Similarly, in Tripura, the study examined the expenditure reports of three national-level parties, the BJP, the Congress and the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M), and three State parties, the All India Trinamool Congress (AITC), the Communist Party of India (CPI), and the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP).

The States for this study were selected based on the availability of expenditure reports for the 2023 Assembly elections, released by the Election Commission (EC). Furthermore, national and State parties that had incurred the highest expenditure in a State were chosen, provided they had released their segregated expenditure reports. The study, thus, highlights the significance of regulating expenditure across all key stakeholders to ensure a level playing field in the electoral arena.

Party expenditure during elections

Expenditure limits are vital for ensuring fair elections and preventing a financial arms race. According to International IDEA, 65 countries around the world, including the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and Brazil, have a cap on election expenditure of political parties. This framework serves as a stark contrast to the scenario in India, where the absence of such caps has led to a lopsided expenditure landscape. In Karnataka, for example, the combined spending of the two national parties, the Congress and BJP, has surged to over 500% higher than that of the two State parties, JD(U) and SP combined. Similarly, in Tripura, national parties outspend their regional counterparts by over 200% (Table 1).

This glaring discrepancy underscores the impact of the absence of spending caps, effectively skewing the playing field in favour of deep-pocketed political giants. The exorbitant sums poured into campaigns tilts the scale of competition, disadvantaging independent or less financially endowed candidates.

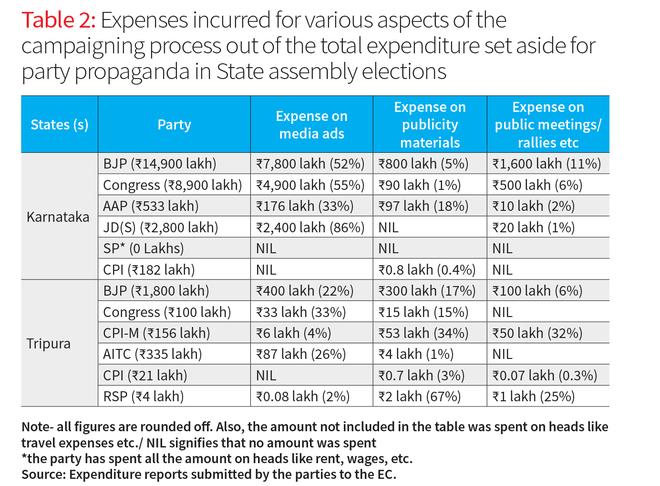

Both national and State-level parties allocated a significant portion of their “general party propaganda” budget to media advertisements, surpassing expenses for rallies and other activities (Table 2). This observation underscores the pressing need for reforms to ensure fair access to media platforms.

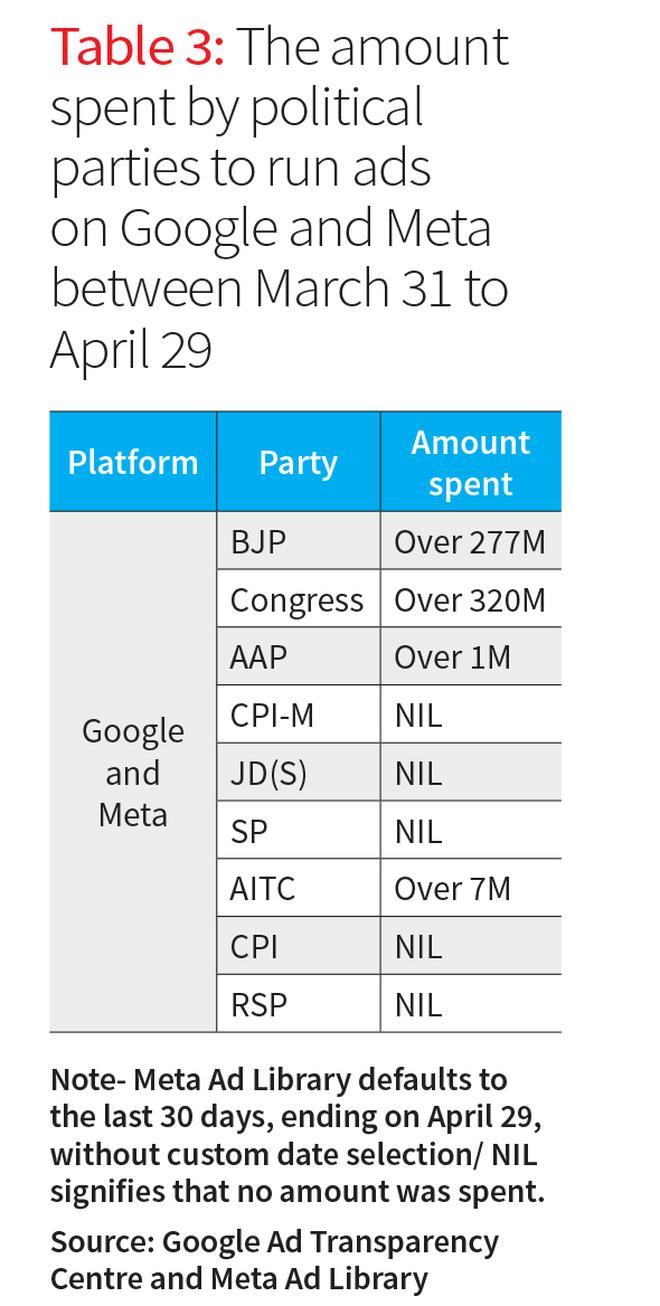

The stark contrast in media advertising expenditure leads one to examine the role of digital platforms like Google and Meta (formerly Facebook) in the ongoing Lok Sabha elections. Big spenders, primarily national parties, are allocating disproportionately higher budgets to ads on these digital platforms. This was highlighted in a recent study of the CSDS-Lokniti (The Hindu dated April 18, 2024). In contrast, State parties were found to have a negligible presence in terms of advertisements on these platforms through their official party handles. (Table 3).

This observation again highlights the need to regulate the overall spending of political parties ensuring that political actors compete based on the strength of their ideas rather than the depth of their pockets.

Role of third-party campaigners

Third-party or non-party campaigners refer to individuals or groups participating in campaign activities during elections, without being formally registered as political parties or candidates. However, in the Indian electoral laws, the term hasn’t been clearly defined. While the issue of regulating the expenditure of political parties is widely discussed and debated, regulation of third-party involvement is often overlooked. The unchecked expenditure and the nature of content posted by third-party campaigners raises serious issues around the lack of transparency and accountability of such actors. (Table 4).

Now that the electoral bond scheme is scrapped, the lack of regulation of third-party expenditure during elections could result in a rise of quid pro quo arrangements and could also lead to an influx of unaccounted money into the electoral process.

Through our study, we found several third-party campaigners on Google and Meta platforms spending substantial sums of money to influence voters for or against a political party (Table 4).

What can be done?

In alignment with global practices, the EC’s ‘Proposed Electoral Reforms’ report in 2016, advocated for the introduction of expenditure ceilings for political parties in India. However, garnering unanimous support for this proposal proved challenging, highlighting resistance from certain political factions.

Similarly, embracing strategies from countries like Australia and the U.K. could offer valuable insights and present tangible models worth considering for India regarding the regulation of third-party involvement. While the former requires formal registration and disclosure requirements for third parties, the U.K. imposes differentiated limits on targeted spending, spending in each constituency, and spending on U.K.-wide campaigns. at certain elections. This is also essential for increasing transparency and accountability, curbing the unregulated flow of money, preventing quid pro quo arrangements, and checking the influx of black money into the electoral process.

Reassessing India’s political funding framework is imperative to ensure the integrity and transparency of elections. Introducing expenditure ceilings for political parties represents a crucial step towards upholding these fundamental principles.

By embracing these measures, India can aspire to international standards of electoral integrity, instilling greater confidence and trust among its citizens in the democratic process.

Sanjay Kumar is a Professor at CSDS, Aditi Singh is an Assistant Professor at O.P. Jindal Global University, and Abhishek Sharma is a researcher with Lokniti-CSDS.