Nearly two centuries after Charles Darwin set sail on the HMS Beagle, scientists embarked on a two-year swashbuckling sea journey around the world to map species of another biodiversity-rich ecosystem — coral reefs. But unlike Darwin, these scientists were more interested in species less visible to the naked eye: microbes.

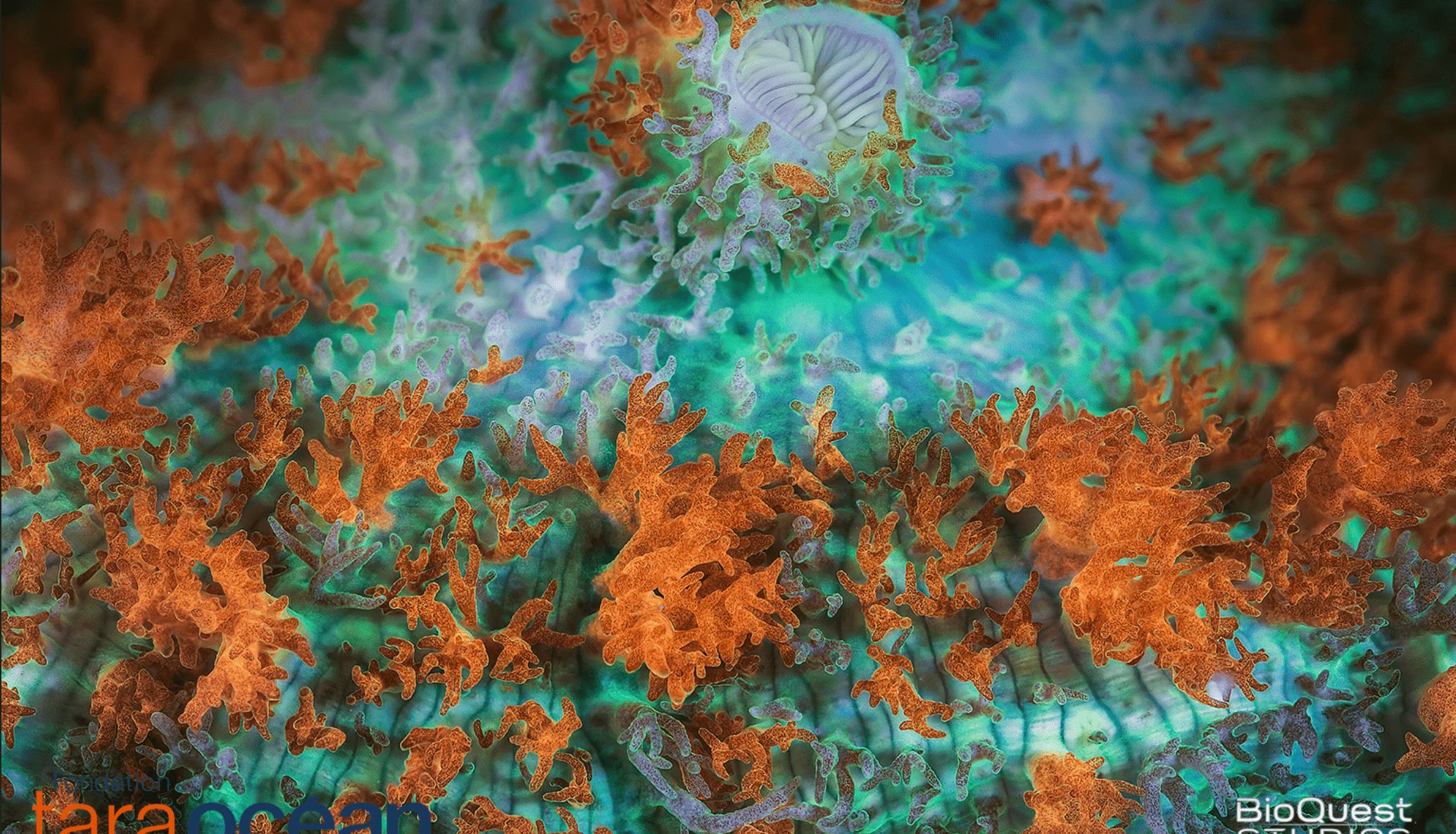

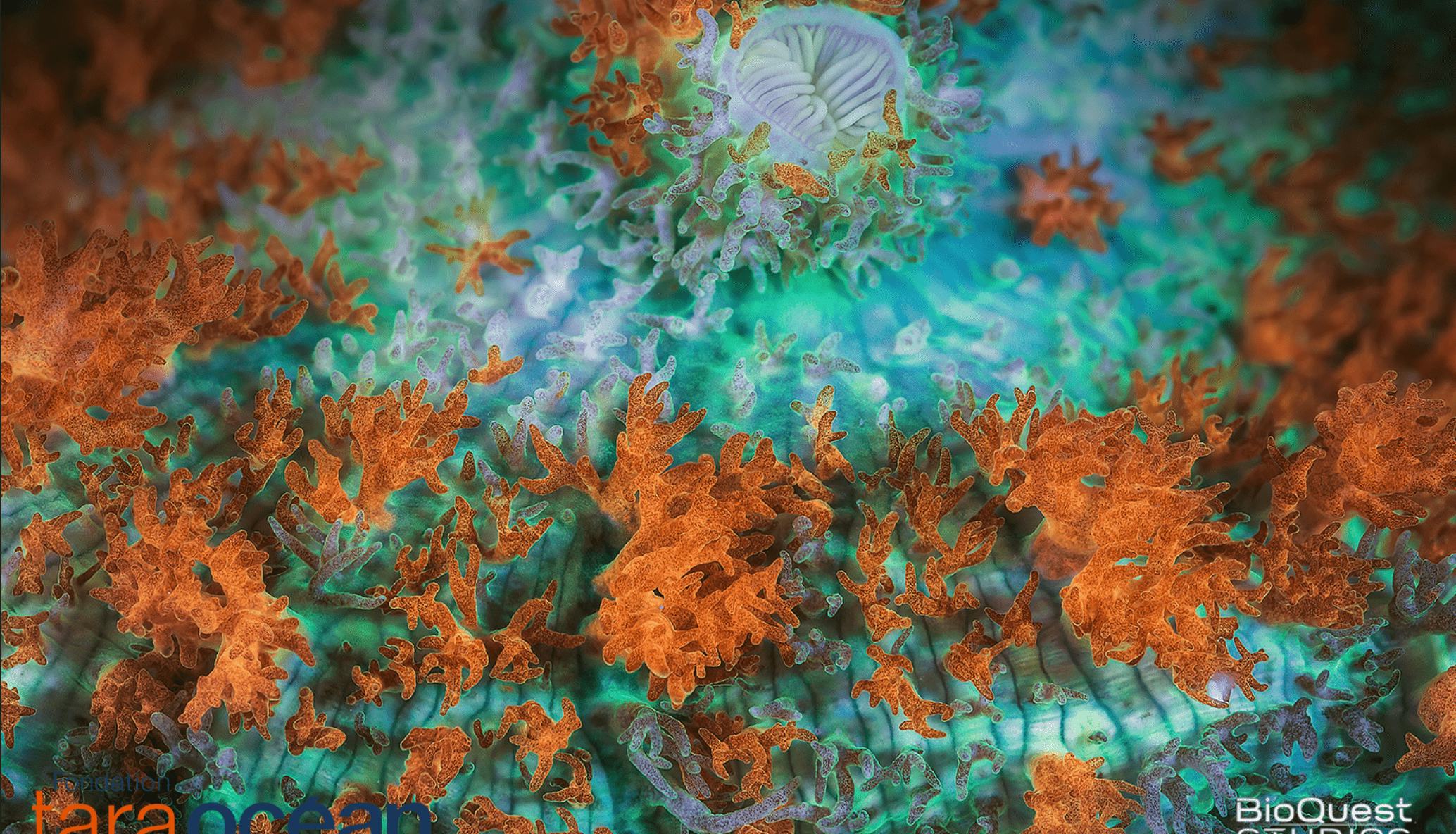

Coral and reef-dwelling fish and plankton form a mutually beneficial relationship with bacteria and other microscopic organisms, not unlike the ones found in your gut or in the dirt beneath your feet.

As warming temperatures threaten to wipe out 99 percent of coral reefs, scientists thought it was high time we understand these microorganisms. Enter the Tara Pacific Expedition.

Between 2016 and 2018, scientists took thousands of samples from coral, fish, and plankton species located in nearly 100 reefs spanning from Panama to the Philippines. The scientists genetically sequenced these samples to determine their microbiome, netting 2.87 billion genetic sequences — roughly equivalent to 50,000 human genomes. The findings of their “unprecedented” sea voyage were published in a suite of papers in the journal Nature Communications on Thursday.

Their findings “indicate the microbiodiversity on Earth is underestimated,” according to study author Pierre Galand, who spoke on a press call with reporters.

The scientists discovered three new species from a group of microbes associated with coral known as Endozoicomonadaceae. Researchers also found that temperature shifts impacted the length of telomeres — repetitive DNA sequences associated with aging — offering clues about the impact of marine heatwaves on corals. The “large richness” in microbial diversity astonished scientists and may offer hope for the future of coral reefs.

“Coral reefs are…an ecosystem in crisis. We need to understand their biodiversity,” study co-author Serge Planes says.