The Navy minesweeper motto is “Wherever the fleet goes, we’ve been.”

The unofficial one, the one that Myron Petrakis remembers, goes something like this: “Put up the gold star, mothers, your son is in the minesweepers.”

In other words, don’t expect your boy to come home.

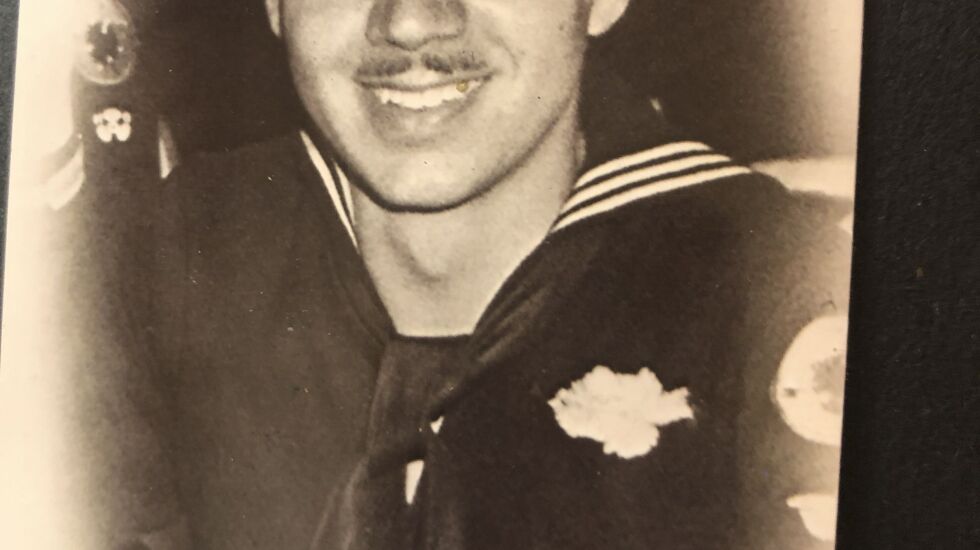

Petrakis came home. He’s 100 years old. He lives at Belmont Village Senior Living in west suburban Carol Stream. It’s been 77 years since he lost his buddy, John Pate, to a mine in the North Pacific. He still can barely talk about it.

“Those are memories. Those are memories,” he said last week, his gaze dropping, his voice trailing off.

Tom Sanders understands the reluctance. He’s photographed hundreds of veterans, including Petrakis, at Belmont Village facilities all across the United States. A permanent exhibition of his work, “American Heroes: Portraits of Service,” opened last week at Midway Airport. His photographs say what a lot of these old warriors either can’t or won’t. Some are too traumatized. Sometimes, dementia has stolen their words.

The portraits capture the resilience, pride, hard-won joy and the indelible stain of war.

Sanders, 38, began photographing veterans for a homework assignment while in college in California. Sanders had what he calls an aha! moment as he interviewed a World War II soldier talking about having his stomach ripped apart by shrapnel. The veteran was 21 at the time — Sanders’ age then.

“He took his canteen belt, cinched it around his stomach and continued fighting,” Sanders said.

Seventeen years later, Sanders is still photographing veterans, although he’s also a professor at Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia.

Sanders has a simple goal for his work.

“I really hope people see the photographs and that it changes their perspective on veterans and makes them more appreciative,” Sanders said.

For many people, though, the photographs may be little more than a blur as they rush to catch a flight.

If they stop and look at George Mueller, 92, who lives at the same facility as Petrakis, they’ll see a man who served in the Army from 1953-55. The caption mentions that, as a teenager, Mueller was in a concentration camp.

He was actually in three, the last being Bergen-Belsen in Germany, where an estimated 60,000 people died — most from starvation, overwork and disease.

“I saw people get beat to death right next to me for infractions — like not coming out of the barracks fast enough,” said Mueller, who only began talking about his wartime experiences in the 1990s.

Mueller remembered seeing bodies lined up against the camp barracks.

“If the guy who was lying there had a warmer coat or something, I would put it on,” he said.

The Russians liberated Mueller, who eventually made it to America, became a pharmacist, got married and raised five children with his wife, Katie, in Glen Ellyn. He also has 15 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

“I’ve got a big stomach that I’m holding in,” he joked when asked about his portrait.

“Holy mackerel!” Frank Kik, 95, declared upon seeing his portrait. The Korean War topographer said he was “humbled” by it.

Petrakis was drafted about the time Americans were celebrating the end of World War II. He was 20 at the start but got a deferment because he was part of the war effort, working at a North Side tool and die maker.

The allies still had work to do.

Petrakis never chose to be on a minesweeper; he trained as a motor machinist. Petrakis likes to say the alphabet saved his life. His buddy Pate’s name came before his and so Petrakis just missed being assigned to the U.S.S. Minivet, sent to remove mines in the Korea Strait, the channel between Korea and Japan. Pate’s ship hit a mine on Dec. 29, 1945. Pate was among the 31 killed that day.

“We were very close friends. I knew he was married and I knew he had a little baby boy,” Petrakis said, sitting in his apartment last week.

Petrakis said he never told his parents about being assigned to a minesweeper.

Petrakis, his gnarled fingers shaking, plucked a card from his wallet. It is covered in layer upon layer of clear tape. The image on the card is so old, it’s almost lost, but if you look closely, you can see the Virgin Mary and Child. Petrakis’ mother gave him the card 78 years ago. She attached strands of her hair and Petrakis’ father’s with melted wax — a Greek tradition.

Petrakis spent most of his life after World War II in Norridge, working in the plastics industry. Catherine, his wife of 69 years, died last year.

Petrakis was lucky in a number of ways. By the time his ship, the U.S.S. Murrelet, arrived in the North Pacific, the Japanese were sweeping their own mines, and the Americans were there to assist, Petrakis said.

Danger always lurked nearby. On one occasion, Petrakis’ ship accidentally entered a minefield and had to back out of it.

“With the captain we had, we were always in danger,” Petrakis said, bitterness in his voice.

But there was only pride last week at the portrait unveiling. Seven veterans came, some in wheelchairs, others rattling to their seats on walkers. Petrakis was invited to speak. He wore an American flag tie and refused help to the podium at Midway.

“Patriotic Americans, I salute you!” he said in a booming voice, before telling the story of how he avoided his buddy’s fate.

Looking on was one of his three children, Stephen Petrakis, 69, who lives in Lodi, Wisconsin.

“The more people pay attention to history, the better off this country will be,” said the son. “The things they went through most people won’t understand — all for a country full of strangers.”