Only an hour away from the hustle and bustle of Toronto lies a quiet old barn in the countryside of Caledon East. A quiet crackling noise comes from the main entrance. Two scientists from Canadian Nuclear Laboratories are busy inside the building, armed with radiation detection equipment. They find contaminated spots on the barn’s walls and floor and mark them with bright orange paint. The beams must be dismantled, the soil excavated, and everything then disposed of in a nuclear waste facility in Chalk River. “This story will never end,” sighs Andrew Stewart, the owner of the property, who looks on as the operation unfolds.

The scientists’ visit is the latest in a long series that began in the 1970s. Stewart’s parents, the previous owners of the land, were not especially worried at the time. The nuclear scientists were always reassuring as they surveyed the property. But Stewart’s dream of a new house on the hill was shattered, and he now hopes to better understand what happened on his land.

Stewart pulls out all the papers related to the property kept by his family. Among the records is a letter from a neighbour sent to them in 1978. In it, the author says that she spoke to a farmer who worked on the property years earlier. She tells them that the story goes back to what she called “the continuing saga of Mr. French’s folly.”

Carl French. The previous owner of the country estate, the man who connects this nondescript Ontario hill to a nuclear scandal involving Canada, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan. It is a saga that has so far been well buried.

Carl French was the former owner of the estate purchased by the Stewarts. His obituary in the Toronto Star in April 1984 described him as a true nuclear hero. The laudatory article recalls that he contributed to the Manhattan Project, the American atomic weapons program during the Second World War. At the time, he was a director of Eldorado, the Canadian mining and refining company that specialized in radioactive materials.

Eldorado supplied radium and uranium to the American researchers, and French was “one of the few people who knew the secret of the nuclear bomb in the making,” the newspaper said. The photo with the article shows a smiling French, and the caption highlights his extensive work with the Canadian Cancer Society. To learn the other side of French’s career, you must go to Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa to view the records of Eldorado and the federal investigations of it.

The story begins in 1937, when French arrived from his native Michigan to take charge of Eldorado’s accounting. The company was only a few years old, founded by Ontarian brothers Gilbert and Charles Labine after the discovery of a deposit of radioactive ores in the Northwest Territories. They operated a small refinery, on the shores of Lake Ontario in Port Hope, to produce purified radium, a prized element used for medical purposes like X-rays and cancer treatments. They also found quantities of uranium in pitchblende, but at the time, it had no real commercial value.

The Labine brothers were skilled prospectors but knew little about big business or the market for radioactive materials. French knew finances and quickly learned the industry and rose through the ranks of Eldorado. Two years after joining the company, he was on the board of directors. The year was 1939, and society was about to undergo a major upheaval. The war sharply increased the demand for uranium.

A British report, known as the Frisch-Peierls memorandum, sparked a new interest in uranium. The two physicists wrote that it was possible to make a high-powered atomic bomb, transportable by airplane, using uranium. Just weeks after the memorandum, Belgium fell to the Nazis, temporarily disrupting the Allies’ access to what had been the world’s most ready supply of uranium.

Eldorado was soon in a very favourable position. The company had vast reserves of pitchblende and its refinery could extract the uranium at an industrial scale. Their lead scientist, Marcel Pochon, was the right man for the job. He had studied in France as Marie and Pierre Curie had continued to make discoveries about radiation, and he was one of the few experts in the world who could manage this kind of production.

Meanwhile, Eldorado signed a distribution contract with a specialist in the field of selling radioactive products: Boris Pregel. The native Russian businessman had been distributing Belgian Congo uranium for years and had extensive contacts throughout the industry.

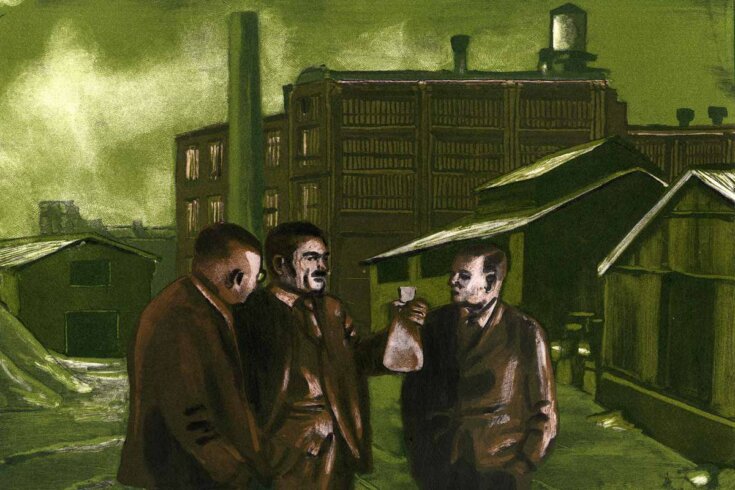

Three men, all skilled in the atomic field in their own ways, thus took the destiny of the Ontario company into their own hands. Carl French oversaw the financing, Marcel Pochon operated the refinery, and Boris Pregel traded uranium from New York. All seemed well, but the three showed ambitions beyond Eldorado.

The three key men of Eldorado received resources and the blind trust of the company’s founders.

Pregel opened talks in June 1941 with uranium-hungry American scientists. In a letter marked “confidential,” one of them, Leó Szilárd, discreetly revealed his intentions to his Canadian supplier: “The five tons of uranium oxide referred to above will be used in experiments which are being carried out by Columbia University under a contract with the National Defense Research Committee.”

Szilárd and many other scientists laid the foundations of the Manhattan Project. Their experiments aimed to create the first chain reaction, a necessary precursor for building an atomic bomb. The scientists required vast quantities of uranium. Pregel sent Eldorado purchase orders of several hundred tons.

The process of getting the uranium to the scientists was complex. The pitchblende mine was in a remote location in the Northwest Territories, on the shores of Great Bear Lake. The material was then transported to Ontario by ship and rail so that Pochon could refine it at a rapidly expanding processing plant. The three key men of Eldorado received resources and the blind trust of the company’s founders.

The arms race reached a decisive milestone when the first atomic pile went into service in a Chicago laboratory on December 2, 1942. A few weeks earlier, Bertrand Goldschmidt, a French scientist, was able to admire the craft in person. He was not there by chance. Goldschmidt was an observer sent by the Montreal Laboratory, also working on the design of a nuclear pile. The British and Canadians joined forces in this field by sending the best available brains to Quebec.

Sheltered from German bombs and close to the raw material, the project was supposed to compete with the Americans’. Unfortunately, the scarcity of uranium blocked research. The year after visiting the nuclear pile in Chicago, Goldschmidt went to Port Hope to speak with Pochon. He estimated that the US program monopolized Eldorado’s planned production for as late as 1946. The British and Canadians were therefore totally at the mercy of Eldorado and cooperation from their American ally.

Later that year, in July 1943, Pregel and French were summoned to the Montreal Laboratory to negotiate the purchase of other radioactive products. The meeting minutes reveal how the two men were perceived: “French makes a very nice impression. Pregel [true to his reputation] as expected.”

The British and Canadians scrambled to obtain fissile material at an affordable cost but came up against the influence of Pregel, who sought to drive up prices. “If we forced his hands by insisting on opening his books, his resentment might lead him to a position of hostility to the Montreal Laboratory and this might have certain scientific consequences which the present Montreal staff would not like,” stated a report from the Montreal Laboratory.

These complaints got back to the Canadian government and echoed those received from the Americans, who were trying to circumvent Pregel’s stranglehold on the market. They even suspected him of being a spy in the pay of the Soviets. One thing annoyed them most of all: the invoices Pregel sent were always in the name of his personal companies, not Eldorado. And French was not fighting to get the contracts back. Several audits also indicated that Eldorado was poorly monitoring the flow of radioactive materials and that quantities were missing.

Realizing it had lost control of a strategic industry, the Canadian government nationalized the company in 1944. The decision came late and the Montreal Laboratory was, by then, subordinated to the American project. This did not dampen the ambitions of the trio. They kept working for Eldorado and maintained their grip on supplies.

The federal government established a commission of inquiry to explore the mysteries of the company. In April 1945, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police forcibly seized the relevant documents at Eldorado and the personal offices of French, Pochon, and Pregel.

The seized documents showed that the three men had committed fraud using a constellation of companies secretly belonging to them. To capture a share of Eldorado’s earnings, French, Pregel, and Pochon had redirected their efforts, profits, and access to materials to the benefit of their own companies. Witness statements indicated that some believed the three were trying to bring about Eldorado’s bankruptcy to regain control of the company’s shares at a ridiculous price.

At the dawn of the anti-communist witch hunts in the United States, rumours of Canadian uranium in Soviet hands resurfaced.

The three men played a critical role in the industry that enabled the production of atomic weapons, but instead of optimizing production to benefit the Americans, British, or Canadians, they knowingly slowed down activities for personal gain. If the Nazis had been quicker in their nuclear research, this embezzling might have had far-reaching consequences.

In December 1945, French and Pochon were arrested in Ontario, while Pregel, living in New York, escaped the dragnet. It is not clear if Canadian authorities planned to pursue extradition, but in the meantime, Eldorado commenced civil action against Pregel, one of his American companies, and French. They claimed for colossal damages: $2,663,362 (US). In today’s terms, that would be more than $45 million (US).

The Canadian government argued that this exorbitant sum was the best punishment and that a criminal trial would have revealed too many military secrets. However, since the explosion of the two nuclear bombs in Japan, several official documents, including the Smyth Report of August 12, 1945, had made public many important details about the development of atomic weapons. As evidenced by the government exchanges we found in the archives, Canada was trying to avoid disclosing embarrassing transactions made by the trio during the war. The details of Eldorado’s settlement were not publicly disclosed.

The abandoned criminal charges and settled civil action coincided with the revelations of Soviet cypher clerk Igor Gouzenko that showed the extent of Soviet spying in North America. The Cold War had begun. Some of Pregel and French’s affairs looked especially bad in this light. Several letters implicating Pregel prove that Canadian uranium was sold to the Soviets as early as 1943, with government approval, even as the Montreal Laboratory struggled to get enough uranium.

Another letter indicates that one of French’s companies had initiated a parallel business dialogue with the Russians at the same time, attempting to cut Eldorado out of the transaction. Finally, there were French’s negotiations with Japan until 1941. Almost up to the Pearl Harbor raid, they were trying to sell radium to Japan.

The report of the Eldorado investigation, perhaps unsurprisingly, does not mention the international negotiations and transactions. In a confidential letter, an investigator wrote to his superior: “In view of current events, I felt it would be better not to mention these so that no one could get an improper opinion but thought you should know about them.”

In 1949, at the dawn of the anti-communist witch hunts in the United States, rumours of Canadian uranium in Soviet hands resurfaced. C. D. Howe, former Canadian minister of munitions, was questioned at a US conference about the sale of uranium to the Soviets during the Second World War. He vigorously denied the allegations but qualified his statement by saying that the sale of uranium to Russia would not have been noteworthy during that period because “I don’t think that the Russians then knew uranium had any importance.”

Karl Fuchs, a Manhattan Project physicist and Soviet spy arrested a few months after Howe’s comments, proved the opposite. The Soviets were perfectly aware of the progress of American research. They were trying to reproduce the same processes in their own laboratories.

Thus, the end of the Second World War brought to light the trio’s dubious activities. The contamination of the Stewarts’ land, however, occurred many years later. French bought the Caledon East property for personal use in the 1950s and soon was quietly conducting work with radioactive materials there. This all suggested that the first investigation did not deter the trio from doing business off the books.

French never stopped developing companies in Chicago, New York, Toronto, and Montreal, in connection with Pregel and Pochon. Many of the companies produced and applied luminescent paint containing radium to watches and dashboards so they could be seen in the dark. These businesses often provided useful cover for experimenting with ways of using and recovering radioactive materials, such as burning radium-soaked rags and other waste. In the course of burning such debris, they discovered a method of developing polonium.

“Polonium was particularly important, as it was used in the triggers for plutonium-based weapons and provided the most accessible source of neutrons for scientific experiments,” explains Gilles Sabourin, a Quebec physicist and author of Montréal et la bombe, released in 2020. This also speaks to the ambitions of Pochon, Pregel, and French. Even as they were under investigation, they were still seeking out new business opportunities. In 1946, one of French’s companies sold polonium to the University of Toronto.

Although these businesses had ample offices and laboratories, they often disposed of their materials in unregistered locations. French used a privately owned farm in Scarborough, not far from his businesses in downtown Toronto, where radioactive ash could be quietly buried or stored in barrels.

When the growing city expropriated the farm in 1953, French transferred the operation to his private estate in Caledon East, the future home of the Stewarts. The remnants of the old installations there, along with family records detailing the decades-long effort to clean up the land, all indicate that the land was home to a similar incinerator.

French sold most of his businesses around 1969 as well as the Caledon East property to a third party in the early 1970s. A few years later, the Stewarts bought the land and only learned of the looming threat beneath their feet when a second government investigation began in the 1970s. A photographer in a downtown Toronto office had discovered that their film was fogging. It turned out that the property was contaminated by French’s work and the ensuing investigation identified the other contaminated properties, including the Scarborough farm—by then a subdivision—and the Stewarts’ estate in Caledon East.

The story of the Scarborough farm made headlines a few years later when George Heighington, a teacher living in a home on top of the contaminated land, rallied his neighbours to successfully sue the Ontario government for negligence. Frank Giorno dedicated his journalism graduation project to the Scarborough contamination.

Reached by phone, he recalled his interview with French in 1980, conducted for an article in the Globe and Mail: “With another student, we went to see him at his home pretending to ask him about his commitment to cancer. Initially, he greeted us warmly. When we started asking about the damage caused by his businesses, he flew into a terrible rage and threw us out of his house.” The Scarborough property was eventually decontaminated. Truckloads of soil were carted away to Chalk River. Work also started in Caledon East, at a lower intensity.

Canadian Nuclear Laboratories tells us that such sites are “historic low-level radioactive waste.” This type of waste “is the result of past practices, which are no longer considered acceptable by today’s standards, and the Government of Canada has taken responsibility for it, as the current owner cannot reasonably be held liable,” a spokesperson said, assuring that it “poses little or no risk to health and the environment in its current form.”

Canadian Nuclear Laboratories continues to monitor the Stewart property and find new “hotspots.” Stewart had once hoped to build a house on top of a green hill with a beautiful view but resigned himself to the fact that it would never happen. Today, there is some hope. Based on latest surveys, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories says they could excavate a full metre of soil off the top of the hill and store it in secure containers on site until a new storage facility in Chalk River is completed. If they discover no further radiation, it is likely safe to build at the location. This quiet hill in Caledon East stands as a testament to our past naivety about the dangers of radiation.