An underwater mountain chain off Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, hosts an "astonishing" array of deep-sea species, at least 50 of which are new to science, researchers report.

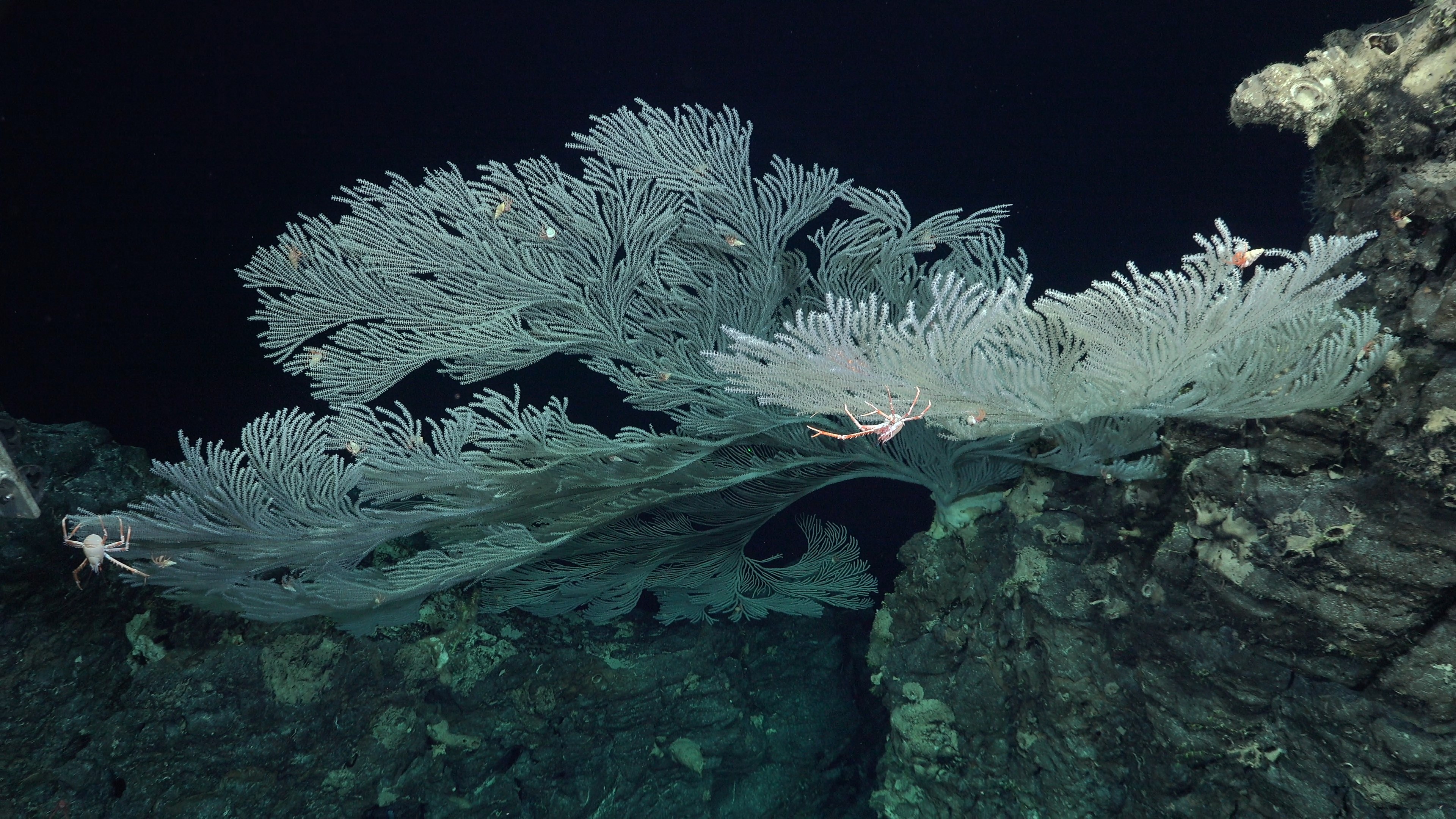

About 2,600 to 4,000 feet (800 to 1,200 meters) below the southeastern Pacific waves, researchers on a Schmidt Ocean Institute expedition spotted the deepest photosynthesis-dependent animal ever found — a Leptoseris, or wrinkle coral, which was already known to science. Other jaw-dropping sights included a jellyfish-like critter known as a flying spaghetti monster (Bathyphysa conifera) and a luminescent deep-sea dragonfish from the family Stomiidae. Both these creatures, along with more than 100 other species, have previously been described by scientists but had never been spotted in this region before. Another 50 specimens, which have yet to be analyzed, are thought to be newfound species.

The expedition followed another Schmidt Ocean Institute research cruise in January that uncovered more than 100 suspected newfound species and a gigantic seamount off the coast of Chile. "The astonishing habitats and animal communities that we have unveiled during these two expeditions constitute a dramatic example of how little we know about this remote area," Javier Sellanes, a professor of marine biology at the Catholic University of the North in Chile, who co-led both expeditions, said in a statement.

While the January expedition mostly focused on the Nazca and Juan Fernández ridges, the new voyage documented marine life on the Salas y Gómez Ridge — an underwater mountain range that extends 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from the Nazca Ridge to Rapa Nui.

Related: 10 mind-boggling deep sea discoveries in 2023

Sellanes and his colleagues crisscrossed the ridge for 40 days in February and March aboard Schmidt Ocean's Falkor (too) research vessel. During the expedition, the team examined 10 seamounts, which are underwater mountains that tower at least 3,300 feet (1,000 m) above the surrounding seafloor. Six of these had not been documented by scientific surveys before, and each seamount harbored its own unique ecosystem, according to the statement.

"The observation of distinct ecosystems on individual seamounts highlights the importance of protecting the entire ridge, not just a few seamounts," Erin E. Easton, an assistant professor of marine science at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and chief scientist at the Schmidt Ocean Institute, said in the statement. "We hope the data collected from this expedition will help establish new marine protected areas."

The researchers explored waters around Rapa Nui with the help of local community members.

"The importance of participating in an oceanographic scientific expedition for Rapa Nui lies in the opportunity to know and better understand the marine environment surrounding the island," Marcela Hey Aravena, a member of the Rapa Nui Sea Council and a Schmidt Ocean Institute observer, said in the statement. "Natural resources, unknown marine species, and climate phenomena that directly affect the community can be discovered through research and exploration."