The day my great-grandfather Andrew Gilhooly was buried at Taranaki’s Ōkato cemetery in early February 1922, Jas Higgins played the Last Post. Neither man had seen active service in the “great war” with which that ritual is most closely associated. Rather, both had served in the New Zealand wars, an earlier series of conflicts fought across the mid-to-late 19th century as part of the colonisation of Aotearoa New Zealand.

In New Zealand and Australia it’s a mark of honour to have ancestors who fought on the Dardanelles or at the Somme or Passchendaele. A national origin myth has been constructed around the Anzacs, replete with a day of remembrance, outsized monuments, and a rich tradition of rituals that are rehearsed annually “lest we forget”.

Nothing like the same emotional (or financial) investment is made in remembering the wars that took place at home. Our own colonial violence, in Taranaki and at Ōrākau, Pukehinahina/Gate Pā and elsewhere, has been relegated to the margins of the national consciousness. It’s an ongoing process of selective historical amnesia that we’re only slowly beginning to address – not so much lest we forget, as best we forget.

This might explain why I grew up knowing next to nothing about my maternal great-grandfather. Yes, there were plenty of stories about his wife (roundly condemned as having been a “difficult” woman) and six children (farmers, priestly prodigies and musical spinsters). However, other than the bare facts that he was born into a poor farming family in County Limerick in Ireland and had served in the New Zealand Armed Constabulary (AC), about Andrew there was only silence.

Last year I wrote a small family memoir, The Forgotten Coast, in an attempt to address that and other silences in my family. As it turned out, the bugling of Jas Higgins at the graveside was the least of the things I didn’t know about my great-grandfather.

Family silences

Andrew became the conundrum at the heart of the book, but he was not the reason I began it. On Christmas Eve 2012, my father died during heart surgery we thought would be routine, but which rapidly became complicated. There were things I wish I’d said to him, and I started writing as a way of doing so.

(Mind you, Dad wasn’t much given to talking either. After he died, just before his funeral, we were able to have him at home with us – and more than once, as we ate, drank and reminisced about him, someone observed that his verbal contribution was not noticeably less than it would have been had he still been alive.)

As the book unfolded, other people and other things began to intrude. It became increasingly clear that if I was to make sense of the silences there had sometimes been between me and Dad, I would also need to address those which draped around other relationships, including some within my mother’s family.

Dad was raised in an orphanage, but married into a large, sprawling family that was – by virtue of three farms, which Andrew and his wife Kate came to control – part of a coastal Taranaki community with a strong sense of identity. Both the people and the place, in the west of New Zealand’s North Island, were important backdrops to my parents’ life together. So I couldn’t really tackle Dad without also dealing with the origins of that context.

The problem was that nobody seemed to know much about Andrew: there was nothing in Mum’s family’s collective memory about where he was born, when he came to Aotearoa, or about his involvement in both the military and agricultural campaigns of dispossession in Taranaki. Nothing other than silence, that is.

So I set about filling in the gaps, the most consequential of which concerned the part Andrew played in the events through which Taranaki Māori were alienated from their land. And the more I learned about that, the clearer it became to me that my own family’s origin story here in Aotearoa is also rooted in historical amnesia.

One of the effects of this is to obscure the uncomfortable paradox that my ancestor, whose own people had been dispossessed by English colonisers, had participated in and benefited from the confiscation of another people’s land.

The Irish model

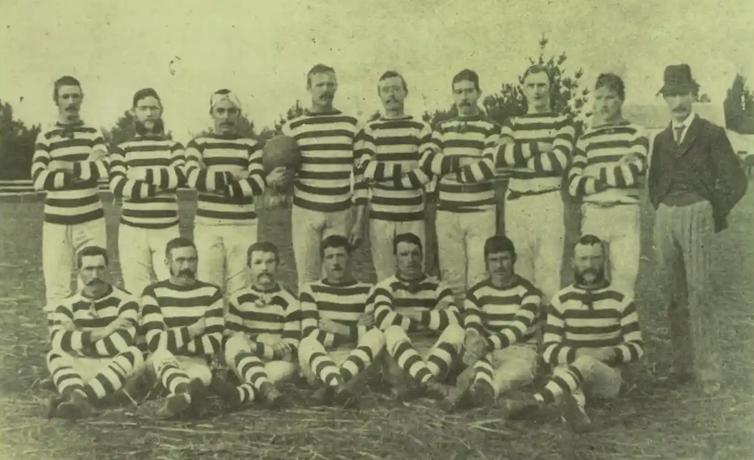

There are two aspects to this contradiction. The first is that for nine years Andrew Gilhooly served in the AC, a hybrid police-military force designed to subjugate Māori, and explicitly modelled on an Irish organisation that had controlled his own people through violence.

The establishment of the AC in 1867 reflected the colonial administration’s desire for a force modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), which was “generally acknowledged [to be] the finest force in the world”. Indeed, New Zealand’s version of the RIC was set up in the very year in which the Irish Constabulary took on the “Royal” moniker, following its role in the suppression of the Fenian Rising.

True, it was far from unusual for Irish Catholics like Andrew to serve in either force. In the 1870s, more than 75% of the RIC’s constables were Catholic (although Protestants accounted for 80% of the officer class), while 37 of the 167 men who joined the AC in the year Andrew signed up (1877) were also Irish-born Roman Catholics.

But the point is that in 1867, New Zealand’s colonial administration copied the template of an institution developed to pacify the Irish and let it loose on another indigenous population.

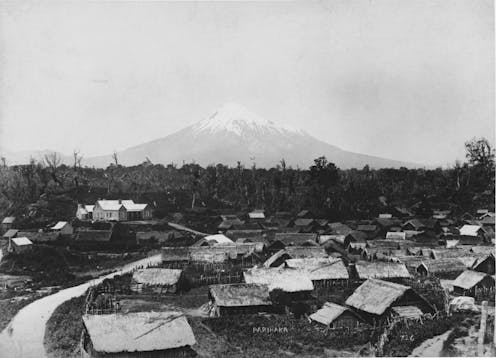

A decade later one of those Irish indigenes – my great-grandfather – joined that force. And four years after that, he was standing alongside 1,588 other military men waiting to start the invasion of Parihaka pā, home to the great Māori pacifist leaders Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi.

Living on confiscated land

The second aspect of the paradox flows from Andrew’s subsequent role in the agricultural campaign that completed the alienation of Māori land in Taranaki. Shortly after his military service ended in 1891, he returned to the province where, in time, he and his wife Kate would come to control three farms that were part of the 1,275,000 acres confiscated from Māori by the colonial state in 1865, and subsequently granted or sold to settler farmers and their families.

As with the establishment of the AC, so too the legislation underpinning the confiscations had Irish antecedents. The two principal statutes were the Suppression of Rebellion Act and the New Zealand Settlement Acts of 1863.

Read more: How NZ's colonial government misused laws to crush non-violent dissent at Parihaka

The former, which was virtually copied from the 1799 Irish law of the same name, suspended the right of trial in particular circumstances so as to “punish certain aboriginal tribes of the colony”. Through the second, which was based on Cromwell’s Act of Settlement in 1652, the colonial state gave itself permission to confiscate Māori land for “public purposes”.

For generations, Andrew’s own people had farmed leasehold land in the township of Ballynagreanagh, land that had passed out of Irish ownership centuries before he was born in 1855. Andrew left behind the “at will” contract (which permitted land owners to evict tenants without reason), the absentee English landlord and the small family plot when he quit Ireland in 1874.

But the irony is that the path he took out of poverty was the same one down which his forebears had been marched into penury.

Big and small histories

The instruments used to displace the querulous Irish – the statutory creation of “rebels”, the parliamentary confiscation of land, the establishment of a police-military force, the administration of inequitable and iniquitous leases – are the same as those subsequently deployed to deal with the troublesome Māori. The difference was that when Māori were on the receiving end, Andrew became the beneficiary of injustice.

Andrew Gilhooly came from poor Irish farming people, who leased a slip of land in the parish of Kilteely from an English landlord who lived in Devon. In the space of a single generation, he and his wife would reinvent themselves socially, economically and politically, laying claim to acreage 16 times the size of that tiny plot in Limerick.

Those new New Zealand acres enabled my great-grandparents to cast off the yoke of Irish poverty and to become respected members of the Taranaki coastal farming community. By the time Jas Higgins played the Last Post for Andrew in 1923, the Irish farm labourer had long since made way for the Taranaki settler-farmer, which was an altogether better thing to be.

Read more: Learning to live with the 'messy, complicated history' of how Aotearoa New Zealand was colonised

Because this transformation was enabled by laws and institutions based on those which had impoverished his own ancestors, it is easy to frame Andrew as the colonised turned coloniser. Certainly that was the unequivocal position I’d reached by the time The Forgotten Coast was published.

But as the book has made its way in the world, and other Pākehā have contacted me with often intimate reflections on their own histories with colonisation, I find that position shifting. An unequivocal view will always offer certainty and clarity, but sometimes at the expense of feeling a little forced.

Perhaps, I now wonder, it is unfair to deduce an intent from the sweeping, systemic forces of history and impute it to a particular individual, as if there is no distinction to be drawn between the “big story” of colonisation and the “small stories” of people like my great-grandfather.

Becoming Pākehā

Whatever his personal culpability, the book has also changed my understanding of time. New Zealand historian Charlotte McDonald rightly questions the standard view of the past as a collection of “actions and speech acts with no pulse, drained of any capacity to affect the present”.

Rather, the three Gilhooly farms generated material and immaterial benefits that continue to shape the lives of Andrew’s descendants. They are a form of living inheritance – and they are, of course, not available to those from whom the land was confiscated.

One of the intangible gains is the clear sense I have of being of and from this place called Aotearoa. I think of myself as Pākehā (a New Zealander with European ancestry) easily these days – but I also wonder when Andrew stopped being Irish and become this new thing, a New Zealander. At what point, if ever, did he cross his personal Rubicon?

Read more: Putting Aotearoa on the map: New Zealand has changed its name before, why not again?

I’ve no way of knowing, and neither can I apprehend what might have been lost in that process. Andrew has and will always have work to do as one of Alan Bennett’s “biddable dead”, his job forever being to leave the tragedy of Ireland for the sunlit uplands of a new world. But I imagine that this process was not uncomplicated for him or for other migrants; that alongside the social and economic metamorphoses there were also splinters of exile and rupture.

Nonetheless, there has been a method to the forgetting that has taken place in my family; a reason the ghost stories of the Armed Constabulary and the farming of confiscated land went untold for so long. My version of the historical amnesia that applies more broadly to the New Zealand wars has allowed me to avoid (until now) the uncomfortable paradox I have walked you through here.

It has meant I have been able to happily claim my place in the pioneer-settler foundation myth, the one that always begins with the purchase of the family farm and ignores the stuff that came before (until now). As the forgetting ends, things must change.

Richard Shaw does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.