The EU’s decision to offer unprecedented rights and freedoms to refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine less than a month after the war began was widely celebrated.

An exceptional measure known as the temporary protection directive, designed to provide immediate protection for at least one year in the event of a mass influx of refugees, was invoked by the EU on 4 March 2022 – for the first time in the bloc’s history. It would mean that “all those fleeing the war” would be granted rights to schools, medical care and employment for one year, the European commission said. “All those fleeing Putin's bombs are welcome in Europe,” President of the commission Ursula von der Leyen proclaimed. German interior minister Nancy Faeser called the temporary protection plan "a paradigm shift" for the EU.

What was not said at the time was how the policy was drawn up to intentionally exclude a considerable number of those fleeing the Russian invasion: non-Europeans.

There were nearly half a million third-country nationals with temporary or permanent residence in Ukraine when the Russian invasion started. Among them were international students, long-term employees and family members of Ukrainian nationals. Like their Ukrainian friends and neighbours, they had to flee their homes, but for many - notably non-white people - their reception across Europe was starkly different.

A preliminary draft of the legislation for the temporary protection directive, seen by The Independent, shows that a clause stating that all foreigners residing in Ukraine on a long-term basis would be granted the same rights as Ukrainians was simply crossed out of the final document. Objections to granting third-country nationals protection had been raised by Polish, Austrian and to a lesser extent Slovakian ministers, according to German diplomatic documents.

A “compromise” was subsequently reached, with the final version of the legislation stating that non-Ukrainians with long-term residency in Ukraine would only be eligible if they were unable to return to their home countries in “safe and durable conditions”.

Inevitably, with hundreds of thousands of third-country nationals among the huge numbers of people who had to flee their homes and cross Ukrainian’s western borders, many ended up in EU countries. Figures from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) shows 325,000 third-country nationals have fled from Ukraine to neighbouring countries since the start of the war. This is based on direct arrivals from Ukraine and does not include onward movements.

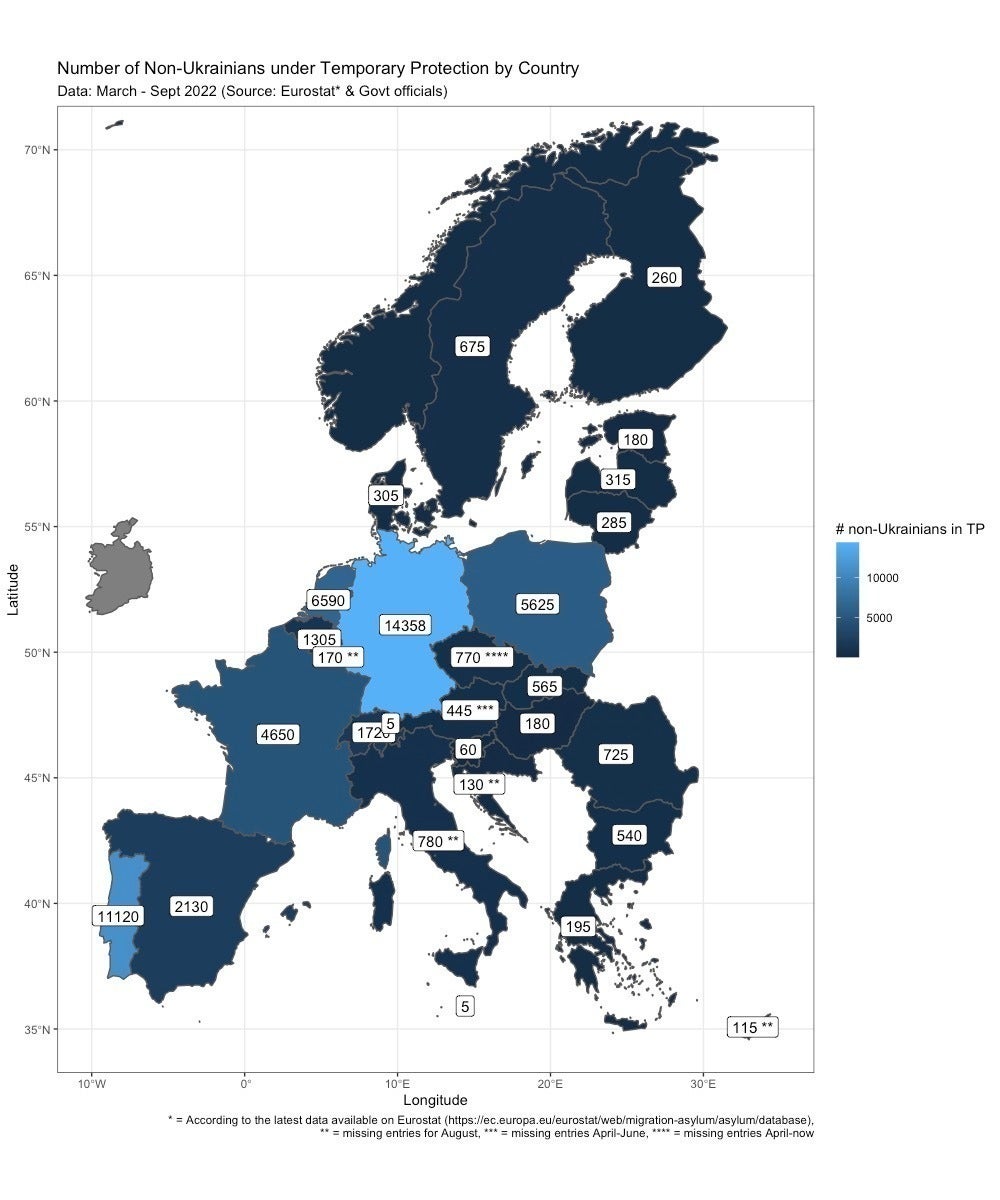

Data collected by The Independent and investigative newsroom Lighthouse Reports, in collaboration with Le Monde, Der Spiegel and De Groene Amsterdammer, reveals that only 54,443 of these third-country nationals were offered temporary protection in EU countries. Unlike the more than 5 million Ukrainian nationals granted protection, many non-Ukrainians were also given time limits on how long they could stay, while others were refused any form of protection, rendering them undocumented. They faced a lottery in the levels of protection they received, with each country granting them different sets of rights and some offering no protection at all.

Strikingly, our data analysis indicates that nearly a quarter of all third-country nationals registered with temporary protection in Europe got it in Portugal, the only country to have granted the same temporary protection rights to non-Ukrainians, including international students who were in Ukraine on short-term (one year) visas. France, a country six times Portugal’s size, has granted rights to less than half as many non-Ukrainians.

Judith Kohlenberger, a migration researcher at the Vienna University of Economics and Business, explains that a lack of clarity around the rights EU countries should be granting non-Ukrainians fleeing the war has allowed each country to apply its own logic when applying the temporary protection directive, with some EU states granting this cohort “zero protection”. She cites the example of Austria, where a third-country national was deported upon attempting to register for protection. In Poland, at least 52 third-country nationals previously residing in Ukraine were detained upon arrival.

The researcher describes a “worrisome” move towards special protection regimes being created for “specific groups of people based solely on their nationality”, with “no individual checking for grounds of persecution but rather wholesale granting of rights”, to which she says there is an “element of racism”.

International students homeless and exploited

Among the nearly half a million non-Ukrainians living in the country were more than 76,000 foreign students, mostly from Africa and southeast Asia. Many had chosen to study in Ukraine because they could not access programmes such as medicine and engineering in their home countries, and the Ukrainian university fees are cheaper and visas easier to obtain than in the rest of Europe. These students were often carrying the hopes and savings of their families into the bid for professional qualifications. Technically only short-term residents in Ukraine, they were not guaranteed any protection under the EU directive.

As a result, thousands of international students are in limbo across the EU, according to the Nigerians in Diaspora Organisation (NIDO), a group working with other organisations in Europe to help African students who fled Ukraine. “We receive dozens of calls from desperate students every day asking for help with accommodation and food, as well as from depressed parents who spent all their money on their children's tuition in Ukraine. It is so bad that some have told us they were considering suicide,” says Chibuzor Onwugbonu, a volunteer at NIDO. Some students have found themselves homeless, while others are facing imminent removal. They are desperate to finish their studies, but many have been stripped of the rights they previously had in Europe and can no longer access higher education.

Abigail*, a 24-year-old medical student from Zimbabwe, was attending the University of Uzhgorod in Western Ukraine when the war broke out. She fled to Berlin and was soon advised to travel west to Heidelberg where she was told a host family would help her obtain documentation and find a job. Instead, she says she was asked to work in their garden and describes being made to wait until after they finished their meals to eat.

She left Heidelberg after three months but struggled to find accommodation elsewhere. She tried six different cities including Magdeburg and Hamburg, but was told there was no capacity and decided to return to Berlin in late August where she finally applied for temporary protection. She began receiving a €360 monthly allowance from the German authorities but it took nearly a month to find her a place in a refugee centre. For lack of a better option she spent three weeks sleeping in Berlin Central train station – the very place that once symbolised the country’s open-armed welcome of Ukraine refugees.

Abigail’s situation can be explained in part by the fact that the rights granted to third-country nationals fleeing the conflict vary between German regions. While Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen are offering six-month non-renewable documents to international students who had been enrolled at Ukrainian universities, to give them time to apply for a visa, other cities have put in place no such mechanisms. James*, a 35-year-old crime scene investigation student from Nigeria who was living in Kharkiv, was denied protection in Munich after a five-month wait, on the grounds that he does not have Ukrainian relatives. He has now moved to Portugal where his application has been pending since June.

We spoke to nearly 30 students in the course of this investigation and all of them paid at least €10,000 per year for accommodation, tuition fees and visas in Ukraine. James’s elder sister had to borrow the money and was counting on her brother’s future salary to help pay it back. In Nigeria, where many of the students are from, public universities have been on strike for six months. For most of them, going home would mean giving up on their studies.

‘Bombs do not discriminate’

Before the summer of 2022, the Netherlands was seen to be a safe destination for international students fleeing the war as the country initially did not differentiate between Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians. But in a dramatic U-turn, the immigration authorities announced on 19 July that they would no longer be processing applications from non-Ukrainians with temporary residence permits and that those who had obtained the status would not be allowed to apply for renewal (whereas Ukrainians can apply for an extra six months). Dutch local authorities have described the act of third-country nationals applying to stay in the country after fleeing Ukraine as an “abuse” of the system.

Meanwhile, in France, where officials say most of those granted protection under the EU directive are family members of Ukrainians, only 200 international students were enrolled in universities. They had to meet the same requirements as other international students: prove that they have €3,750 in their bank account and secured accommodation or €7,500 in their account without accommodation. These conditions were waived for Ukrainian students.

According to local organisations, at least 10 non-Ukrainian students received “obligations to leave the French territory”, a letter threatening them with deportation. Nissia Messaoui, a 28-year-old from Algeria who was a paramedical student in Odessa, received the letter in May, after having overstayed a month visa granted to her on arrival to the country in February. The government has since announced that it would temporarily freeze expulsion measures to give students until late September to apply for student visas. This means that those that haven’t met the criteria for student visas still risk being deported.

International students who experienced the trauma of fleeing Russia’s war feel that, while their Ukrainian classmates were met with open arms, they were met with discrimination and xenophobia. The treatment of these young people, who had sunk serious investment into their education and represent the middle classes of their home countries, has not gone unnoticed internationally. While the students themselves have seen hopes dashed, their treatment has triggered accusations of racism on the part of Europe.

Dutch MEP Thijs Reuten says the omission of international students from the temporary protection directive was not simply an oversight, but a conscious decision aimed at excluding non-Europeans, suggesting an element of racism. “It seems almost certain to me that the countries of origin of the international students played a role” in the language adopted by the EU council regarding non-Ukrainians, he explains.

“The Commission agreed too easily to this concession,” Reuten adds. “They should have stuck to the directive: the principle was for every nationality to be treated equally. That was the strength of the directive. People who were studying full-time in Ukraine were, just like their fellow Ukrainian students, a part of Ukrainian society [...] Bombs do not discriminate.”

*Some names have been changed

Additional reporting by Anna-Theresa Bachmann, Halima Salat Barre, Beatriz Ramalho Da Silva, Coumba Kane, Irene van der Linde and Steffen Lüdke