Nord Stream 2 is a 745-mile pipeline stretching between Ust-Luga near western Russia’s border with Estonia and Greifswald in northeastern Germany, intended for the delivery of natural gas to central Europe via the Baltic Sea.

Construction on the project was completed in September 2021 at a cost of £8.3bn but it has yet to receive the necessary European regulatory approval to permit its operator, the Russian state-owned gas giant Gazprom, to turn on the taps.

That may now never happen, after German chancellor Olaf Scholz announced that the pipeline would be blocked in retaliation for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Thursday 24 February.

Mr Scholz said Berlin would have to “reassess” the project in light of recent developments, warning: “That will certainly take time, if I may say so.”

Right now, the chance of the project ever being given the final approval appears vanishingly remote.

Nord Stream 2 would have enabled Russia to pump an estimated additional 55 billion cubic metres of gas to Germany each year, doubling its present capacity and increasing its regional energy dominance.

The original Nord Stream pipeline was completed in 2012, and runs parallel with its new companion and likewise terminates at Greifswald but has a different point of origin – Vyborg, on the northern coast of the Gulf of Finland.

Perhaps most significantly given the present crisis, the two pipelines together would have allowed Russia to send gas west by means other than directly through its neighbour’s territory, which it previously relied upon and for which Kyiv received lucrative transit fees.

Russian president Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer, is said to have resented Ukraine’s independence since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, particularly its desire to secure greater military protection by joining Nato.

Like his annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 or subsequent recognition of pro-Russian separatist regimes in the eastern industrial heartland of the Donbas, the pipeline could be seen as further punishment for Kyiv’s rejection of his influence.

His Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky, has previously warned that the Nord Stream project represents a “dangerous geopolitical weapon” and is not alone among world leaders in fearing that Russia could have used it to exert political leverage over the EU by threatening to withhold gas in winter if its political whims are not indulged.

Germany, under its previous chancellor Angela Merkel, had long dismissed those blackmail fears as hysterical, insisting the project was a purely commercial venture that will enable it to heat 26m homes and aid its transition away from nuclear power.

However, with Europe already mired in an energy crisis and Gazprom recently declining to replenish its stores on the continent to the expected extent in order to shield itself from exposure, Russian ruthlessness should be taken as a given.

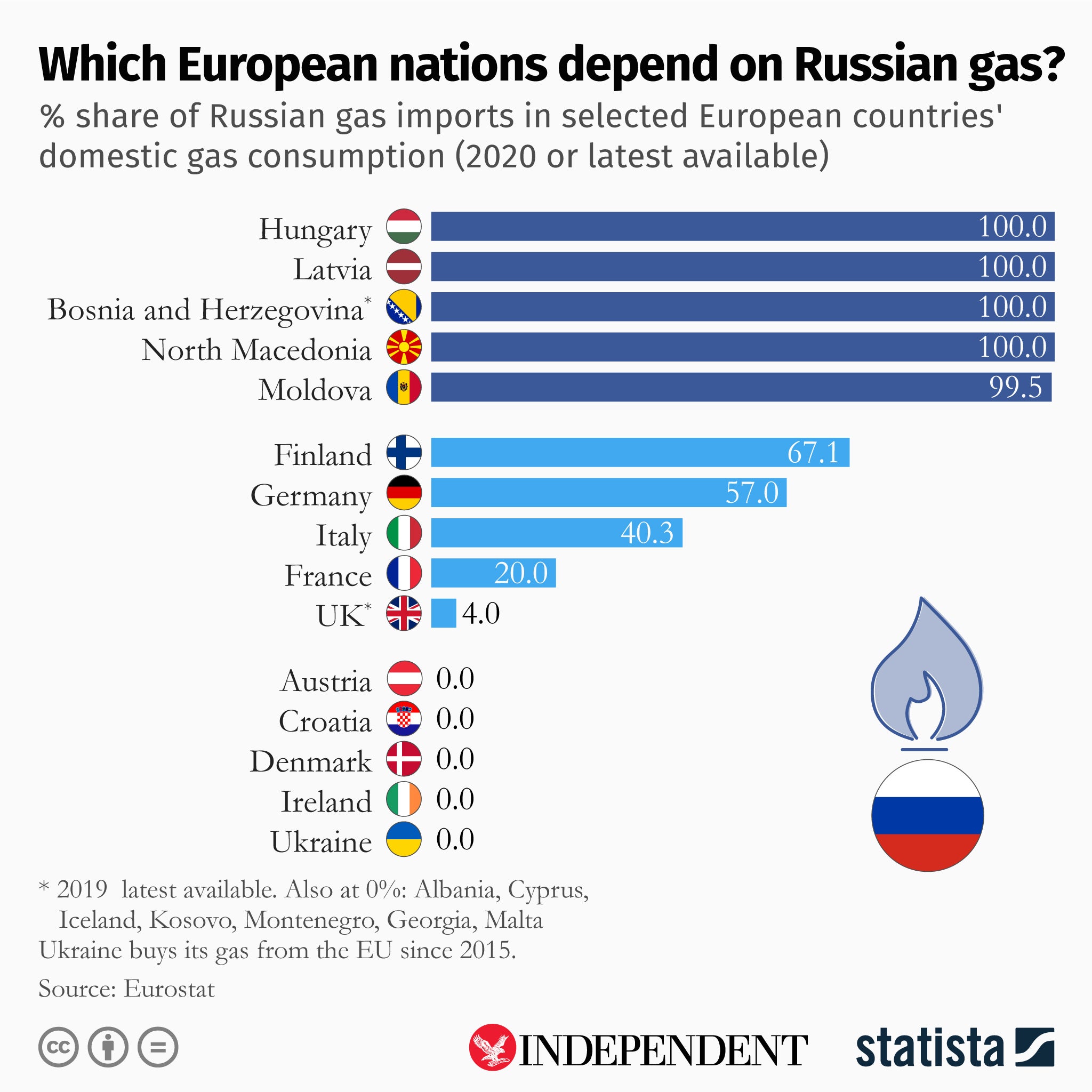

While the UK receives only 4 per cent of its gas imports from Russia, Germany receives 57 per cent and Hungary, Lativa, Bosnia and North Macedonia 100 per cent, underlining the power of the cards Moscow holds, with American investment bank Stifel warning recently that gas prices could quadruple should war break out as it now has.

Prior to his announcement, Mr Scholz had visited the White House to discuss tactics with US president Joe Biden, after which the pair gave a joint press conference at which the American warned Mr Putin they would not hesitate to “end” Nord Stream 2 should he make the “gigantic mistake” of invading Ukraine.

His secretary of state, Antony Blinken, meanwhile moved to reassure Europe that the US would support its energy needs should any difficulties arise.

“We’re working together right now to protect Europe’s energy supply against supply shocks, including those that could result from further Russian aggression against Ukraine,” he said during a joint press conference with EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell.

Mr Blinken said coordination efforts with allies and partners includes “how best to share energy reserves in the event that Russia turns off the spigot, or initiates a conflict that disrupts the flow of gas through Ukraine”.

The US has long been opposed to both pipelines – even Donald Trump attacked it at a fractious Nato summit in Brussels in July 2018.

UK defence secretary Ben Wallace likewise signalled in advance that stopping the pipeline being activated was “one of the few chips that can make a difference”.

Germany was previously reluctant to commit significant military support to Ukraine, despite pressure from the international community to do so, presumably because of its tangled energy concerns.

However, it does have other potential options for the supply of gas beyond Nord Stream 2, including taking deliveries from Norway, the Netherlands, Britain and Denmark instead, so need not feel held to ransom.