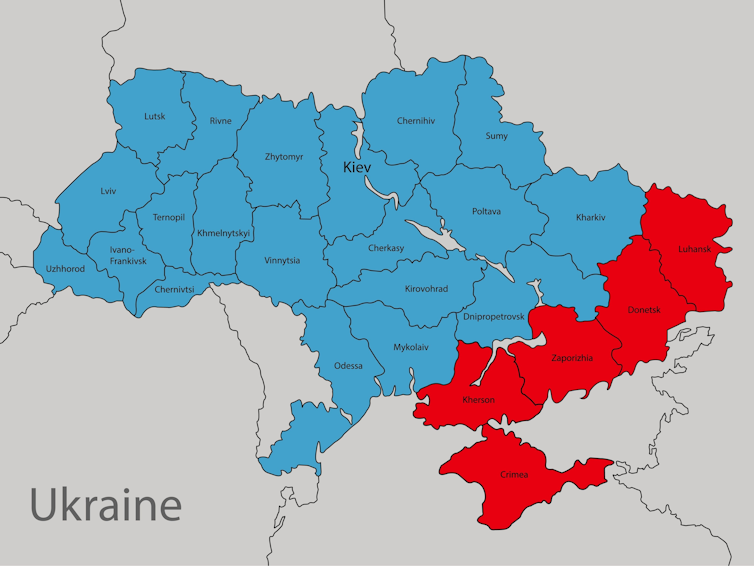

Four parts of Ukraine that are occupied by Vladimir Putin’s war machine are to be formally annexed by Russia. Or, as the official Russian news agency, Tass, puts it: “The official signing ceremony uniting four new territories with Russia will be held on Friday, September 30, at 3pm in the Kremlin.”

“President Putin will deliver a voluminous speech at this event,” said Kremlin spokesman, Dmitry Peskov – exciting news for the 85% or more of the people of these Ukrainian provinces who, according to Tass, voted in favour of returning to the motherland. Although reports of pro-Russian functionaries going door-to-door to encourage people to vote might hint at these “referendums” not being as free and fair as the Kremlin would have the world believe.

The referendums, which many western countries have dismissed as being “sham” votes, are a rerun of a similar process by which Crimea was annexed by Putin in 2014, according to Stefan Wolff of the University of Birmingham and Tatyana Malyarenko of the University of Odesa, who covered that vote for The Conversation at the time.

Read more: Crimea votes to secede from Ukraine as EU considers sanctions against Russia

Like the Crimea referendum, the latest ballots “violate almost every conceivable democratic standard,” they write, adding that: “No credible international observers were monitoring the vote in the occupied areas or in Russia or Crimea, where refugees from Ukraine have also been called upon to vote.” But this will give Putin something to help sell the war to an increasingly restive population back in Russia.

Read more: Ukraine war: west condemns 'sham' referendums in Russian-occupied areas

Tatsiana Kulakevich, an affiliate professor at the Institute on Russia, University of South Florida, gives us the background on the four newly annexed provinces: their relationships with Russia, their shifting demographics, and the fact that most of the people there, despite what Russia says about the referendums, do not want to be part of Russia.

This is our weekly recap of expert analysis of the Ukraine conflict. The Conversation, a not-for-profit newsgroup, works with a wide range of academics across its global network to produce evidence-based analysis. Get these recaps in your inbox every Thursday. Subscribe here.

Russian exodus

Meanwhile, Putin’s decision to call up more than 300,000 reservists into active duty has caused turmoil and unrest at home. Reports of riots and violence at drafting centres have been accompanied by dramatic footage of long queues at Russia’s borders with Georgia, Finland and other neighbours as men of conscription age attempt to escape the call up.

Martin Jones, a professor of international human rights law at the University of York, believes these men should be regarded as refugees under international law. While refugee law doesn’t automatically protect people evading conscription, it has historically recognised a range of circumstances in which individuals fleeing conscription are entitled to protection, not least that they might unwillingly be forced into situations where they are involved in war crimes.

Read more: Ukraine war: why Russians fleeing conscription should be treated as refugees

Russians have been flooding into neighbouring Georgia since the very beginning of the invasion in late February. Then it was mainly for economic reasons as international sanctions began to bite. Now it’s to avoid the draft, especially as reports from the battlefield make for ever more grim reading if you are Russian.

Natasha Lindstaedt, a specialist in authoritarian regimes – particularly post-Soviet Russia – visited Georgia recently and gives us a picture of how the people there are reacting to the war. It’s complex. The leader of the ruling Georgia Dream party has ties to Russia’s business elites, while former president Mikheil Saakashvili, who as a former governor of Odesa province, is close to Ukraine, languishes as a political prisoner.

Ordinary Georgians, meanwhile, vehemently oppose the war. They also harbour fears that – having been invaded by Russia as recently as 2008 and possessing a run-down defence force – they could appear as low-hanging fruit for a Putin smarting from military humiliation in Ukraine.

Back in Russia, as we have heard, there is widespread discontent about the decision to mobilise. There was no parliamentary debate, just a presidential decree – and not even a decree they are able to access and read in full, as parts are redacted.

Lana Haworth, who lectures in law at King’s College London and studied for a law degree in St Petersburg, provides the background to Putin’s extraordinary powers. This “super-presidency” as it is known, was set up in the 1990s by his predecessor Boris Yeltsin, but Putin’s own reforms in 2020 have made Russia a virtual autocracy. So while the mobilisation is legal, according to the Russian constitution, many people refuse to see it as legitimate.

Read more: Ukraine war: Vladimir Putin's mobilisation order was legal – but will Russians see it as legitimate?

From the battlefield

You would imagine that the huge numbers of extra troops that conscription will give Putin to deploy in Ukraine would give Russia an irresistible advantage. But most analysts thought at the very start of the war the might of the Russian war machine would overwhelm Ukraine within days – and look how wrong that proved to be.

Basil Germond, who researches maritime strategy and geopolitics at Lancaster University, sees this mobilisation as typical of Russia’s “continental mindset”, the idea that if you throw enough men and materiel at an enemy, you are bound to prevail. Ukraine, meanwhile, has a more flexible command structure which allows for more nimble thinking in the field. And Russia’s new conscripts are unlikely to be the highest calibre troops the country has ever sent into battle.

Throughout the war, we’ve been reading regular updates from the Ukraine government as well as the British Ministry of Defence and US intelligence agencies. One traditionally thinks of intelligence product as something that is closely guarded and kept in files marked “top secret”. But as you can see here, the MoD is putting out regular updates based on its analysts’ assessments of the state of the conflict, or – in this case – the likelihood of widespread draft dodging in Russia.

Huw Dylan of King’s College London and Thomas Maguire of Leiden University, both of them intelligence experts, have looked at why governments might want to make their intelligence public and what the advantages and pitfalls might be.

Read more: Why are governments sharing intelligence on the Ukraine war with the public and what are the risks?

Ukraine Recap is available as a weekly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.