The Russian invasion of Ukraine has triggered, in the words of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, “the greatest threat to European stability since the Second World War.”

Since then, not a single day has passed without powerful stories and shocking images of bombardments and casualties circulating online.

In a recent CBC interview, Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan examined how history has become “an instrument of war” used by President Putin to lay claims on Ukraine through a one-sided interpretation of the past.

According to Putin’s distorted view, Russia’s future and its place in the world are at stake and these depend on Putin’s goal: to “demilitarize and denazify Ukraine.”

The disciplinary tools of history are important to help people today understand two critical related things: Stories mobilize people in powerful ways; and the ability to analyze, challenge and judge stories’ credibility is at the heart of empowering citizens to participate in and create democratic societies.

The past, in all its complexity

Historians, MacMillan observes, have a central role to play in making sense of war. She notes:

“We must do our best to raise the public awareness of the past in all its complexity.”

Like MacMillan, we believe that leaders like Putin cannot mobilize for military operations without invoking the past, or some interpretations of it.

In Dangerous Games: The Uses and Abuses of History, MacMillan writes that historians are highly qualified to interrogate one-sided, even false, histories that politicians use “to bolster false claims and justify bad and foolish policies.”

History and the power of knowledge

In the past decades, there has been a push in Canada, England and other nations to implement programs of study aimed at developing historical thinking, historical literacy or powerful knowledge. All these terms refer to approaches that seek to develop a “historical gaze” or a distinctively historical way of seeing past and current issues.

The rationale driving this is a democratic one: all future citizens should have equal access to the knowledge resources necessary to exercise agency in their world.

To learn a discipline is to learn to reason and organize information in specific ways, drawing on discipline-specific concepts and ways of thinking.

History, as a discipline, can provide us with powerful ways to move beyond the acquisition of stories (as content knowledge) to learn about how these stories were created, including their degree of certainty and their purpose. Such a disciplinary way of thinking helps people understand history as a tradition of inquiry and opens up a distinctive way of seeing world conflicts.

Reasoning with source materials

Studying history involves developing a deep knowledge of the human past understood as the histories of power relations. It also means:

developing knowledge of the particular historical contexts of past and current conflicts;

providing education in how knowledge claims can be made, understanding, for example, that claims about the past emerge through questioning and reasoning with source material, not simply by reassembling memories and fragments of the past into a story;

and finally, it involves developing an understanding of historical narration — both how narration can be used to develop new understandings and insights and how it can be abused to sustain fixed political positions.

‘Making sense’ of war?

How can studying history help young people make sense of the war in Ukraine?

A historical perspective on the current war in Ukraine can enable understandings of both the events unfolding in the present — as understood by different opposing parties — and the ways in which narratives are being used to influence perceptions.

A historical perspective on the causes of the invasion of Ukraine would avoid simplistic explanations.

Instead, history teachers might build a situation model to explain Russia’s invasion by putting it in short-, medium- and long-term contexts, looking for both enabling and determining factors in order to explain why the invasion took place.

À lire aussi : Stop telling students to study STEM instead of humanities for the post-coronavirus world

Taking a historical perspective would certainly need to move beyond the Putin-centred explanation and ask questions about Putin’s thinking, psychology and intentions.

It would ask questions about the contexts that enable his actions to have deep consequences in the world.

Evaluating competing narratives

To take a historical perspective is also to move beyond explanation, and to start asking questions about multiple stories that different parties offer, to make sense of what has happened and to shape our responses.

This means considering differing historical perspectives on events and analyzing different points of view on the conflict: Russia/Putin, Ukraine, Canada/NATO.

It also means exercising narrative competence and judgment to compare, deconstruct and evaluate the competing narratives that circulate about the events and that are part of the process of mobilizing action and shaping the future.

À lire aussi : Commemoration controversies in classrooms: Canadian history teachers disagree about making ethical judgments

Why, one might ask, has a euphemistic narrative that speaks of “special military operation,” not “war,” been actively disseminated by the Russian government notably in schools and what ideological function does that serve?

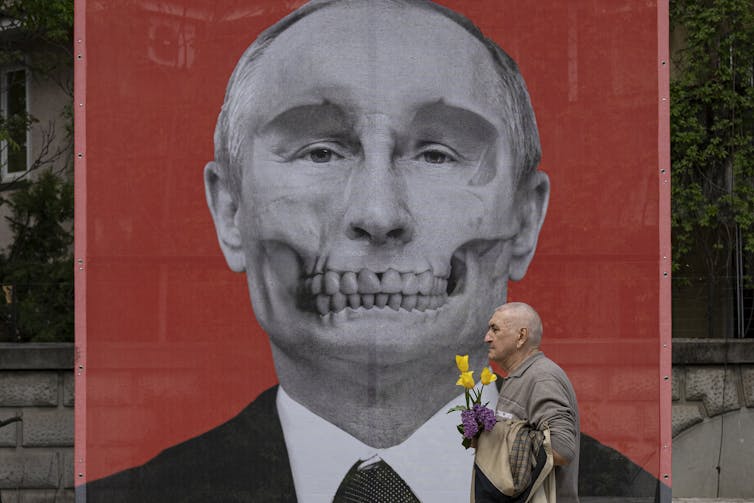

Why, on the other hand, have “Vlad the mad” psychologized narratives arisen in the West? What function do they serve and what do they obscure and reveal? History has things to teach about what responsible and realistic narratives look like and about the kinds of narrative we should question and find incredible.

Learning to detect patterns

Traditional education, focused either on content knowledge or on skills, is inadequate to the task of educating young citizens to navigate complex futures — as the Organization for Economic Co-opration now recognizes.

To get our bearings on world issues, including climate change and war, we need what education researchers Michael Young and Johan Muller call a “Future 3” education, grounded in disciplinary ways of knowing, not simply in bodies of knowledge. For them, “Future 1” education simply reproduces dominant knowledge traditions and fixed stories. “Future 2” education eliminates distinctive forms of knowledge to emphasize general skills that ultimately limit our capacity to understand history — and its uses and abuses.

As Michael Ignatieff sums it up, “to get our bearings, to figure out what to do, we need to understand how we got to this point … we need to be able to see the pattern in the carpet.”

À lire aussi : How analyzing patterns helps students spot deceptive media

To do that, we need not to be taught more stories or facts but, crucially, to be taught how to look and look critically at narratives aiming to shape perceptions of both the past and the future.

Stéphane G. Lévesque is current policy analyst and expert for the Government of Canada.

Arthur Chapman ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)