I pack my bag, take batteries, cables and SD cards for my digital recorder. I ask for media accreditation from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence before leaving, on my return to the field for the third time since the Russian invasion, with the objective of documenting the war.

In the plane to Poland, just in front of me, a young Ukrainian is also going back. The psychological weight of his return has nothing in common with my humdrum preoccupations. I imagine that he’s establishing himself again there after a long exile, or perhaps just going back for a few days to see relatives who have remained there.

As we come in to land, he holds his phone in his hand. He scrolls through his photos: clouds of smoke from a huge bomb, another explosion, a cat (he zooms in), a baby, more photos of the same baby, yet more of the baby but this time in its mother’s arms, a sports car being repaired in a garage, the ruins of an apartment block, a naked woman (he doesn’t dwell on this photo), friends in a restaurant all smiling at the camera.

Back to Ukraine – ethnography of a resistance movement

Chronicling the war from an ethnographic perspective isn’t such a new thing for me. I tried to do this over the course of numerous visits to Syria from 2012-18, then in Ukraine, with the aim of better understanding the impact of the conflicts on people’s daily lives.

I’ve always thought this work should have meaning. It’s not commenting on unfolding battles, tactical advances or artillery deployment. All of this is important in its way. But it’s a quite contrary notion I grapple with as a researcher: that war is no longer seen as a matter for ordinary people; that it’s now abstracted, spoken of only in terms of accounting numbers killed and wounded, and territory lost or won.

One morning in February 2022, a mass of ordinary people, who had had no natural disposition to live through such an experience, found themselves swallowed up by the war. They administered First Aid to their compatriots, they became humanitarian volunteers, drivers and fighters… They were overtaken by the world’s violence.

From that day on most of them have taken part in the war effort. They have been, variously, eager, patriotic, courageous, succumbed to weariness and exhaustion, terrified, confident: so many distinct moods across the range of lived experience.

In the first few weeks, they barely had any time to think about what positions to take on the conflict. They were carried along by events and the huge-scale mobilisation of friends and acquaintances. For months they lived in a condition of fear and frenzied activity. In just a few days they found themselves collectively involved in a series of scary and exciting adventures.

Lives transformed

It’s useful to recall everything that’s happened over recent months and how those who have lived through them have been changed by daily contact with violence. To consider this process through participant-observation puts one on a very human level. Participant, because it involves living several weeks with a group of activists, picking up again with those I’d left last August, date of my previous journey. They live in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Kramatorsk.

In the interim, Vitaly – a volunteer from Kharkiv who became a fighter, who I’d met a year ago – has died in Bakhmut. Dania, one of his friends, has also been killed.

The others are still alive. In Kyiv or Kharkiv, they’ve resumed a lifestyle a bit nearer normal. Bombings have become rarer, shops reopened, residents returned, volunteers have ceased duties and gone back to home lives. Return to a normal life happened almost as quickly as descent into war.

On Independence Square in Kyiv, better known to us as the Maidan.

It’s a matter of leaving the war behind after previously being so absorbed in it. One day, the enemy moves away, home troops are no longer in evidence; the duties of daily life lead people to think about their own needs, go back to work and began get their life back, now that’s been saved – and to consider their future.

Resuming a “normal” life

After months of an unsettled, uncertain existence, almost without a break, Ukrainians have rediscovered a life which is familiar, ordered and more predictable. Something happened to them which, from now on, nothing else in their lives will outdo. At the end of my stay, I’ll be going back to Kharkiv to see people who stood down from war readiness when the front line had moved about 100km from the city. My first question for them is: how did you go back to a semblance of ‘normal life’?

Escaping a cycle of violence arguably involves huge costs: to lose all the intensity and solidarities around the conflict, that sense of a useful existence and total absorption in the clarity of the present.

It also involves living with memories – frightening images of a world collapsing around you.

A road bridge in Irpin, destroyed during clashes in 2022, is in the midst of reconstruction. Provided by the author, click to enlarge.

I imagine that incidence of depression and mental illness is growing. I see all the difficulties of re-establishing yourself in an ordered world, and yet leading a much more precarious life than before because, for starters, of the many buildings and workplaces that have been destroyed.

The opposite is doubtless also true – perhaps Ukrainians will rediscover the joy of recklessness and, proud of having taken part in countering the Russian attack, will gladly embrace the pleasures of a simple life free from danger.

But the war hasn’t disappeared. It grinds on, only further away. They’re worried less about their own lives than those of those dear to them closer to the frontline, still in the grip of war’s torment.

In the Donbas, the battle rumbles on

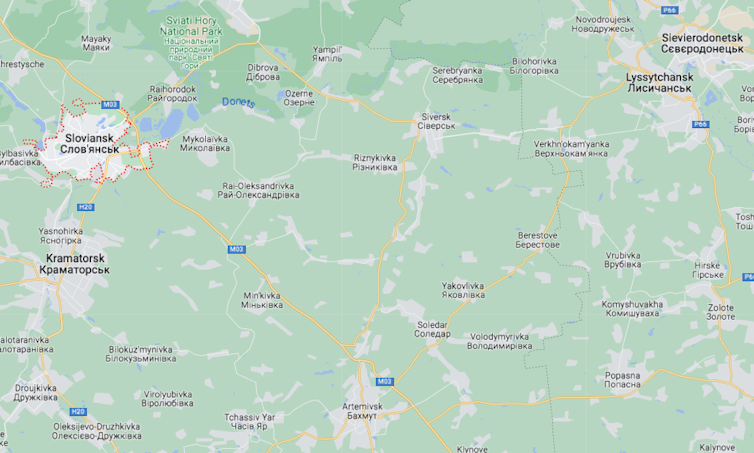

Some volunteers continue their struggle. I’ve just come back to the town of Kramatorsk in the Donbas to locate Mark, who has been volunteering since the start of the conflict.

Photo of Mark during a emergency relief hand-out in the Kramatorsk region. Provided by the author, click to enlarge.

With others, he continues to deliver parcels to stricken towns not far from Bakhmut and Chasiv Yar, where the fighting is at frightening level of intensity. Until recently, he was also involved in evacuating civilians from territories under threat of being taken by the Russians.

These volunteers have also been transformed

They’ve got into routines, in organisations that have become more structured rather than just being forged out of passion. They’re living both in the war, and for the sake of it. They’ve become used to living under a great deal of stress, a life narrowed and constrained by danger and necessary defensive precautions. Probably, they’ve minimised the reality of violence in their heads.

As they’ve acquired experience, do they perceive things differently? Have their tolerance thresholds changed? Do they feel the same shock that they did the first time? I don’t know if there’s a person alive who can get used to haunted faces, wounded bodies, to life in the rubble, in cellars or in collapsed apartment buildings, living side by side with ruination.

In Syria, as the war dragged on longer, I could observe how deep suffering could turn faces grey, exhausted and joyless. The more one sinks into a condition of violence, the more one forgets how to live. Desperate sadness can penetrate the bravest spirit. What’s it like for Ukrainians nearest the frontline? How is their outlook on life and the enemy transformed?

PHOTO Near Irpin, a graveyard of vehicles for the most part riddled with bullets and destroyed during combat has become a place of remembrance. (Provided by the author, click to expand/view.

To look ‘the flesh of the world’ in the face

I’ve also got my habits. I need to fight against reducing what I see to the banal. It’s a real internal battle to leave oneself still surprised by reality, to be seized by the moment and not to over-explain the unknown. Good observers stand out for their attention to detail. The task isn’t so much about collecting good material, as picking out apparently tiny actions to draw rich lessons about the everyday experience of war – its driving forces, its structures, its exhilarations and its setbacks.

An ethnographic study seeks to understand over its duration the effect of war on ordinary people’s lives. It also looks to turn what’s geographically far away into eye-witness accounts, through the simple act of looking. To look is to engage, as director Claude Lanzmann said about his film Shoah. The role of ethnographic research is to look closely at the ‘flesh of the world’, to make people see it.

To write an ethnographic account of war is also to join in efforts to tell stories about people’s lives while everything is collapsing around them. It’s not impossible that later, these people will be tempted to forget what happened, in order to restart their lives. There will also come a time when the supply of conversation partners keen to hear their stories will dry up. That’s a cruel moment of loneliness and erasure, after they’ve played a heroic role in history.

Already, after months of fighting, public attention is waning. The reader is getting used to the war, too. The emotions of the early weeks after the invasion in February 2022 quickly fell back again, marches of solidarity with the Ukrainian people thinned, the fury about lives destroyed dried up. Whether one was thousands of kilometres away or at the centre of the conflict, a common attitude has emerged: to diminish the reality of the violence, to avoid being in a state of fearful vacillation.

The dilemma is always such a painful one: to distance oneself from reality, to protect oneself from being as a consequence complicit with the horrors of the present. Another attitude, which to me seems a totally desirable one, is to be faithful to events and take a position vis-à-vis them. This requires “a sense of the real and a certain moral flair”, as Jean-Jacques Rosat wrote in his preface to the collection of George Orwell’s ‘As I Please’ columns for Tribune.

Translation by Joshua Neicho

Romain Huët does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.