The UK government has published a white paper on the regulation of artificial intelligence (AI).

While an important step, the white paper is not enough to set the UK on the path to taking full advantage of AI. The government uses white papers to lay out proposals for future legislation. They act as a platform for further consultation and discussion, allowing changes to be made before a bill is presented to parliament. The country is far behind its allies on this issue and success is not assured. I’ll outline what the UK needs to do urgently to realise its ambitions.

AI regulation and economic growth are synergistic, not in conflict. The desire to ensure the use of AI is safe and fair and the drive to innovate, increase productivity and stimulate the UK economy are important complementary goals. Regulation is not only important for protecting the public but also linked to the promise of future economic investment in AI. That’s because regulation provides certainty for businesses – a framework to structure plans and investment.

There are four stages to AI regulation: setting a direction, passing binding requirements, turning them into specific technical standards, then enforcement. The white paper is step one of this process. It lists five principles to inform the responsible development of AI, including accountability and an ability to contest decisions. Yet the EU and US are already at step three – setting standards.

Waking up

UK companies and universities are at the forefront of AI research, and the country has smart and well-respected regulators. However, the UK was relatively slow to act. The EU was quicker at getting agreement between 27 states than the UK was at getting agreement between two government departments. The US, even with a divided federal government, beat the UK to market.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has woken up to the issue and is now moving things forward. The next steps will be to insert the UK into international AI standard-setting and ensure the country’s regulators are coordinated enough to underpin the growing market in AI assurance – testing and auditing to confirm AI systems comply with standards.

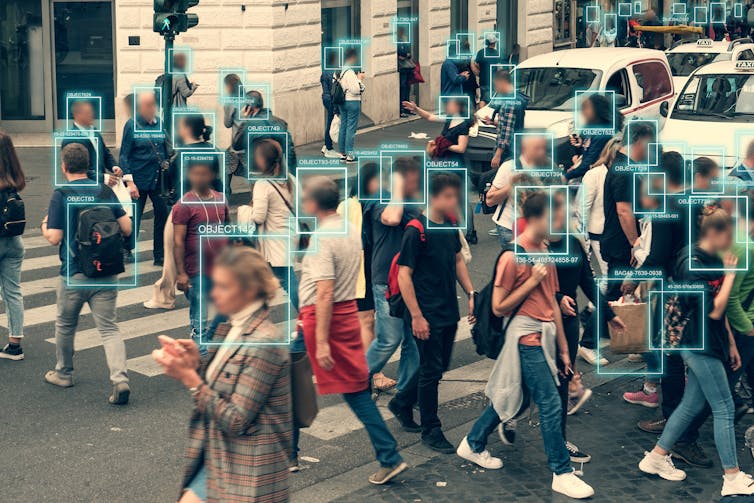

A number of events in recent years underline why trust in the technology is vital. Several years ago, AI was used to try and catch welfare fraud in the Netherlands. Large penalties were applied based on a risk calculation by the algorithm. This led to thousands of families’ lives being ruined.

In the UK A-level grading fiasco exam grades were determined by an algorithm, instead of being scored. Almost 40% of students received grades that were lower than anticipated.

Standard-setting in the EU and US is surging ahead. The EU is moving towards passing its AI Act. This will set high-level requirements for all companies selling AI products considered “high-risk” – those that could affect a person’s health, safety or fundamental rights.

This would cover AI used in hiring, grading exams or in healthcare. It would also concern AI in safety-critical settings like policing or critical infrastructure. The EU has already started setting technical standards, a process that should finish in January 2025.

The US started a bit later, but quickly developed a standardisation process through the federal agency NIST (the National Institute of Standards and Technology). The EU’s AI Act has a serious “stick” in terms of big fines. The US version is more carrot: companies that want to sell to the federal government will have to follow NIST standards.

Setting the bar

EU and US standards will set the bar for the rest of the world. The EU is a market of 450 million rich consumers, and an influential “regulatory superpower”.

Other countries will probably copy EU rules and global companies will want to follow these rules everywhere, as it will be easier and cheaper. The US is a market of 330 million even richer consumers, and has all the big tech companies, so NIST standards will also be influential.

The EU and US have every incentive to arrange a stitch-up. This could happen through the EU-US Trade and Technology Council.

The main international alternative is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). China is influential there, so it might make sense for the US and EU to lock in their standards and present them as a fait accompli to the ISO.

If the UK cannot find a place in this process, it could become a rule-taker rather than a rule-maker. Instead, the UK should try to broker an arrangement between the EU and US, so that it is at the table when these standards are set.

The UK’s recent International Technology Strategy championed similar ‘interoperable’ technical standards so the country’s allies could work together easily. This would help UK companies export AI products and services to the US and EU.

Standardisation would create a new multi-billion pound market for “AI assurance”, which the UK wants to capture as much as possible of. But it will have to move swiftly, as cities such as Frankfurt and Zurich are already on the case.

Ducks in a row

The UK has world-leading consultants, auditors, lawyers and AI researchers to assess and ensure AI systems are ethical and safe. Yet taking advantage of this business opportunity will require coordination. Otherwise, different regulators might ignore certain topics, leaving gaps. The opposite could also happen, where different regulators oversee the same issues - creating confusing overlaps.

A strong central body should oversee coordination, assess risks and support regulators. However, businesses will need clarity over which regulators cover what, and over what timescale.

The UK has the opportunity to ensure that international AI regulation and standards benefit the country, drive economic growth, protect families and create new markets. Although it has been slow out of the starting gates, the country can still catch up to, and even lead, the pack.

Haydn Belfield is at the University of Cambridge's Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence (Associate Fellow) and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (Academic Project Manager), and is also on the Advisory Board of Labour for the Long Term.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.