The UK government has increased its 25% levy on oil and gas companies – the UK energy profits levy – to 35% from January 2023 as part of its November 17 Autumn statement. The scheme has also been extended by two years to March 2028. Combined with a new 45% windfall tax on the profits of electricity generators, these taxes are predicted to generate £14 billion next year, according to UK chancellor Jeremy Hunt.

But even in normal times, the profits of oil and gas companies that operate in the UK continental shelf are subject to a 40% tax rate, rather than the usual 19% rate on corporate profits. The levy introduces a top-up corporation tax of another 35% (25% before the 2022 autumn statement), raising the rate of tax on the profits of companies such as BP and Shell to 75% from January 2023 (65% until the end of 2022).

Government documents, show that fewer than 35 groups pay the existing 40% tax and in 2021 seven groups footed the bill for 95% of the total tax take. The number of taxpayers and their relative share of the overall tax take should be broadly similar for the energy profits levy.

But it’s not the size of the UK’s windfall tax that should be adjusted; a stronger design is necessary to bring in more money, more efficiently to boost government spending. This is particularly important given the recent news of Shell paying no windfall taxes on bumper UK profits this year. This is a direct result of the design of the UK levy. An increased rate does not address this problem at all.

Taxing energy profits

There are different kinds of windfall taxes. While some tax normal profits, others focus on excess profits. This means a certain sum is collected from an organisation that has done particularly well due to circumstances outside of its control.

Indeed, windfall profits do not arise from a savvy investment in an innovative piece of technology, rather, they happen when companies benefit from external factors. Rising interest rates in banking, for example, or higher commodity prices in energy, typically bring in more money for firms in these sectors. We have certainly seen that this year, when the world’s five biggest oil companies shared £50 billion in profits. When extraordinary profits are purely down to external factors, such sectors become prime targets for windfall taxes.

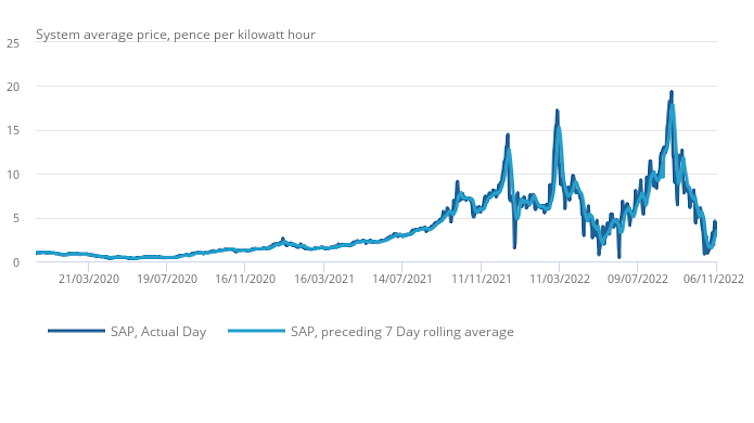

UK gas prices rose by 110% during one week in 2022

How do windfall taxes work?

Windfall taxes should be a convenient way for governments to raise a large amount of revenue quickly. And this is particularly useful at times like this when people are suffering due to the same circumstances from which some companies are profiting. As an added benefit for policymakers, windfall taxes on excess profits are what economists call a “non-distortionary tax” because they do not incentivise companies to change behaviour in order to escape or reduce their tax liability.

Governments need to be careful about creating uncertainty for businesses, however. If a windfall tax is introduced as a temporary measure, companies are left to wonder how long they need to factor it into their plans. This uncertainty can be alleviated with policy commitments, or by introducing the tax as a permanent measure.

Alternatively, a company might try to avoid the tax by relocating its activities to another country. In the case of the UK’s current energy levy, this is unlikely because other countries or regions competing for such investment are also considering excess profit taxes.

The EU introduced a levy in September on profits that exceed a 20% rise over the average taxable profit since 2018 (this will cover 2022 and 2023). US President Biden has also signalled the potential for a tax on excess energy profits.

Taxing UK energy profits

There is a lot of research to show how to design a strong windfall tax that will bring in solid revenues for a government and its citizens. The UK’s energy profits levy does not align with these findings in two major ways:

It is a temporary top-up tax on corporate profits that does not rely on a clear definition of excess profits, but research shows that successful energy sector levies tend to be permanent taxes based on a clear measure of excess profits, rather than arbitrary price thresholds.

It offers a large investment super-deduction for companies that invest in UK energy projects, which means that, for every £1 million of new investment, oil and gas companies receive more than £900,000 of tax relief. This is a massive subsidy.

This is how some oil majors have avoided paying very much tax on their UK profits in recent quarters, despite massive gains this year. A super-deduction, particularly at a time of high uncertainty about the economic outlook, is wasteful.

My research shows that investment incentives are not effective amid highly uncertain circumstances because companies hold off on new investment projects. A super-deduction during volatile times only ends up subsidising projects that would already have gone ahead in the absence of the tax break.

A stronger design

As the UK emerges from two devastating economic crises little more than ten years apart – the COVID pandemic and the 2007-8 global financial crisis – it faces an unprecedented cost of living shock partly driven by an uncontrollable rise in energy prices.

As things stand, the energy price guarantee and the energy bill relief scheme to help limit households’ gas bills are projected to cost around £43 billion in total this year. The current forecast for the energy profits levy estimates it will raise £14 billion.

It would be naive to think that a few billion pounds scraped off the top of energy company profits could be the ultimate cure for the tough winters ahead. But improving the design of the energy profits levy – in particular, scaling back the super deduction – would allow energy companies to take on a greater share of society’s burden by paying for some of the cost of living support households will need this year.

İrem Güçeri does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.