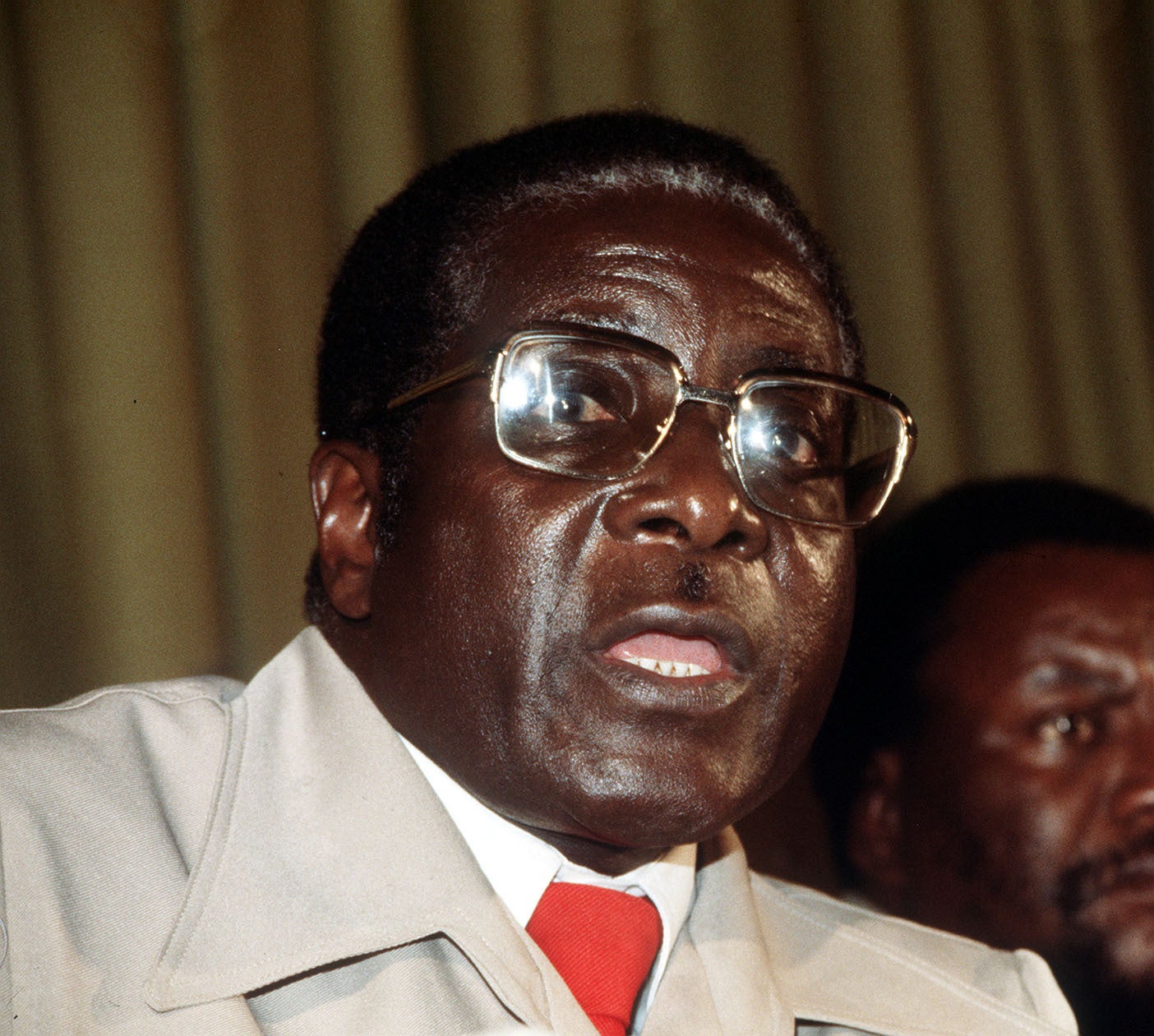

Military action to remove Robert Mugabe was deemed not a “serious option” by the Foreign Office, despite mounting frustration within Tony Blair’s government over the Zimbabwean dictator’s refusal to relinquish power, newly declassified files reveal.

Documents released to the National Archives in Kew show that Downing Street pressed the Foreign Office to devise new strategies to exert pressure on Mugabe, as the former British colony descended into widespread violence and economic chaos.

A No 10 adviser warned the prime minister that the deteriorating situation could prove a “real spoiler” to his ambition of making 2005 “the year of Africa” at the Gleneagles G8 summit.

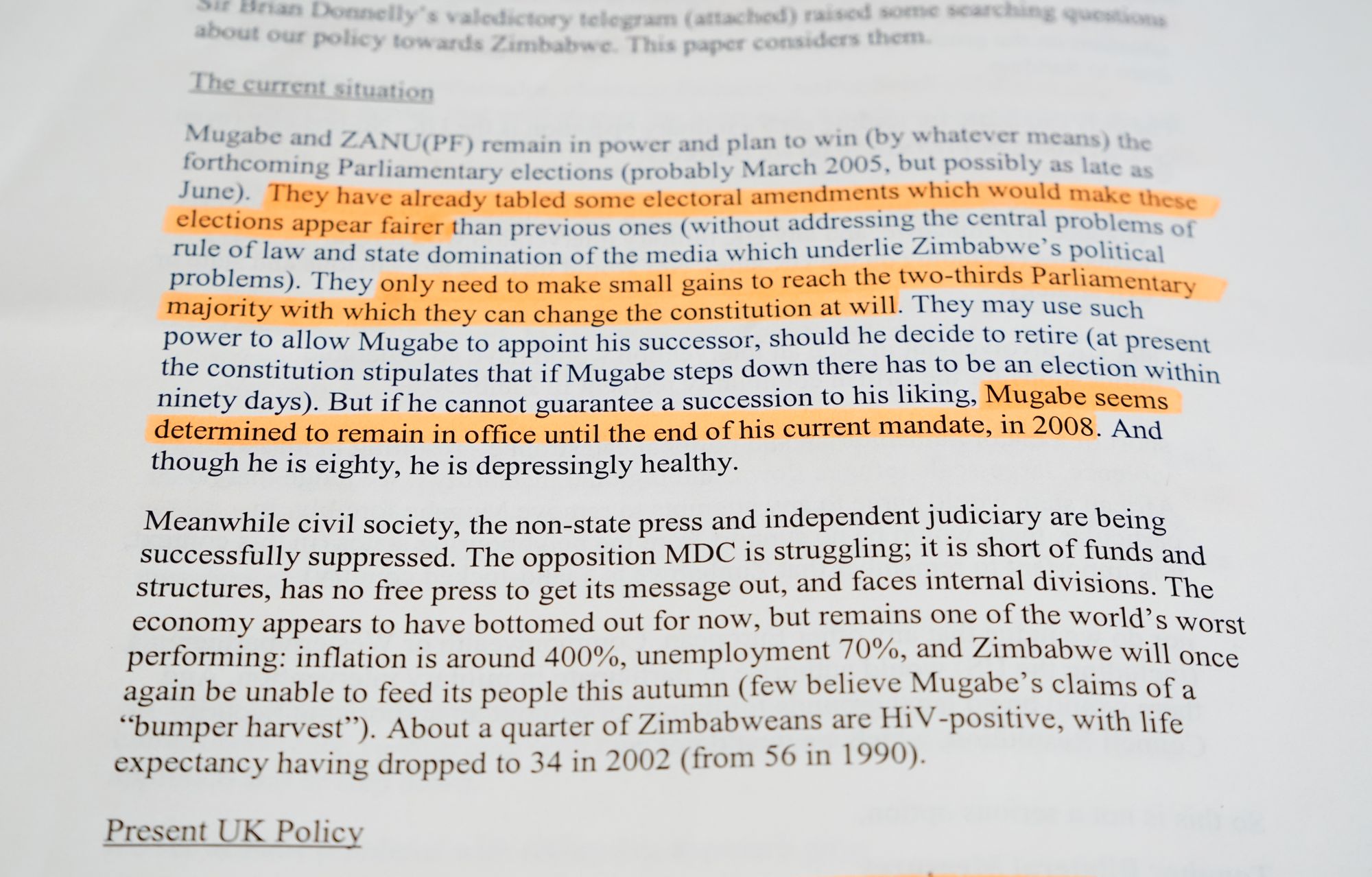

However, the Foreign Office was forced to admit that few effective avenues existed for intensifying pressure on the veteran Zanu-PF leader who, at 80, remained “depressingly healthy” and determined to stay until he had secured a succession to his liking.

An options paper, drawn up in July 2004, was quick to rule out any use of military force. A year after the UK joined a US-led coalition to overthrow the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, it said that this time Britain would be on its own if it tried to invade.

“The only candidate for leading such a military option is the UK. No one else (even the US) would be prepared to do so,” the paper said.

“Any UK military intervention would result in heavy casualties (including on the UK side). Nor would there be any obvious end state or exit strategy.

“Short of a major humanitarian and political catastrophe – resulting in massive violence, large-scale refugee flows and regional instability – we judge that no African state would agree to any attempts to remove Mugabe forcibly.”

Thabo Mbeki, who was president of South Africa at the time, subsequently claimed that in the early 2000s, Mr Blair had tried to pressurise him into joining a military coalition to overthrow Mugabe.

Mr Blair strongly denied the claim, but the suggestion that military action had previously been mooted may explain why, in 2004, the Foreign Office was so quick to make clear that it was a non-starter.

The files show that Mr Blair was, however, attracted to a suggestion by the outgoing British ambassador Sir Brian Donnelly, who urged him to engage with Mugabe to try to persuade him to step aside once parliamentary elections due in early 2005 were out of the way.

In a valedictory telegram to the prime minister’s foreign policy adviser, Sir Nigel Sheinwald, he pointed to Mr Blair’s success in getting the Libyan dictator Colonel Muammar Gaddafi to give up his weapons of mass destruction after years of being treated as a pariah by the West.

“I can well understand why you and the prime minister might shudder at the thought given all that Mugabe has said and done,” he wrote.

“I also recognise Mugabe’s unique place in our demonology creates some special problems with UK public and parliamentary opinion. It is a political call.

“All I can say is that you steeled yourself to do it with Gaddafi, another megalomaniac, often irrational de facto dictator. The payoff more than justified the effort.”

Mr Blair appeared to like the idea, writing: “We should work out a way of exposing the lies and malpractice of Zanu-PF up to the election and then afterwards, we could try to re-engage on the basis of a clear understanding of what that means.

“I can see a way of making it work but we would need to have the FCO work out a complete strategy.”

But Foreign Office officials in London were deeply sceptical, warning that such an approach had been tried before and failed, and would risk “looking like a U-turn for nothing”.

At the same time, they warned that imposing new sanctions, on top of the international measures already in place, would be counterproductive, hurting ordinary Zimbabweans while allowing Mugabe to persist in his “big lie” that the UK was responsible for all the country’s woes.

More than two decades after the liberation struggle against white minority rule, which brought him power, they concluded, Mugabe would not step aside without “overwhelming pressure” and the only realistic course was to “hang firm” until he chose to go of his own accord.

Sir Brian’s successor, Rod Pullen, wrote: “He is not mad (as some suggest), nor is he simply clinging to power out of fear (as others suggest). Rather he comes across as believing he has business to finish.”

In the event that business was to remain unfinished for another 13 years until he was finally deposed in a coup in 2017, aged 93.

Cooper orders Foreign Office to review ‘serious failures’ in Alaa Abd El-Fattah case

Revealed: Mandelson’s 2005 general election warning to Blair over rival Brown

Blair refused to share intelligence with Ireland over Sellafield threat - archives

No 10 blocked release of Blair’s call with French president after Diana’s death

Farage is still popular despite racism claims, poll finds

Ed Miliband to invest in solar power to create ‘zero bill’ homes