On February 16, as Congress leader Rahul Gandhi prepared to enter Uttar Pradesh by road, from Kaimur district in Bihar, 21-year-old Avinash Singh, from Vaishali district in Bihar, was on the train to Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction in U.P.’s Chandauli. While both journeys were taken in the hope of change, Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Nyay Yatra, covering 15 States, had the privilege of choice; Singh’s had the compulsion of poverty.

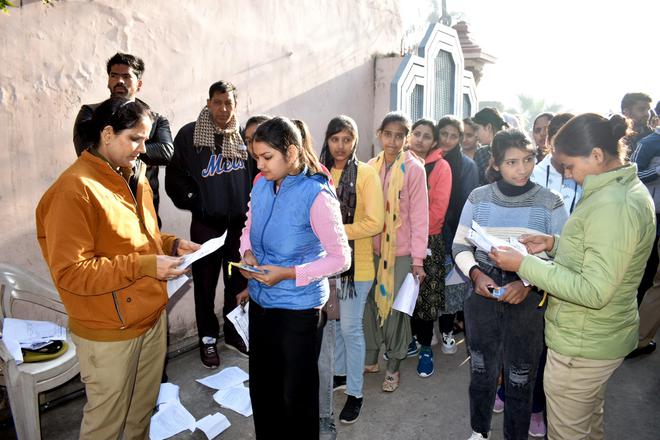

Singh was headed to Lucknow to take the written part of the entrance examination for recruitment to the Uttar Pradesh police’s junior-most position of constable. The exam for 60,244 posts was held between February 16 and 18 in 2,385 centres across all 75 districts of the State. The jobs, for women and men between 18 and 25 years, were advertised in December 2023. Registrations from December 27, 2023 to January 16, 2024 led to 48.17 lakh aspirants submitting forms.

Of these, roughly 2.5 lakh candidates were from Bihar, about 43 lakh hailed from U.P., 98,400 were from Madhya Pradesh, 74,769 from Haryana, 97,277 from Rajasthan, 42,259 from Delhi, and 3,404 from Punjab. Eventually, 5.03 lakh did not take the exam. U.P. Police is among the largest police forces in the world, with more than 2.25 lakh employees working at maintaining law and order in India’s most populous State, which is home to more than 24 crore people.

A school graduate, which made him eligible to apply, Singh’s parents are agricultural workers in Goraul village. They have no land to their name. “When they get work, they earn ₹400 a day. I want to change their fortunes,” he says, sitting on the ground at the Charbagh railway station, Lucknow, 48 hours after having arrived to take the exam. He is waiting to board the Lucknow-Varanasi Superfast to Varanasi, from where a connecting train will take him to Patna, Bihar’s capital.

On the platform, where there is no place to move, Singh, in a black vest with a knapsack on one shoulder, flicks on his low-budget smartphone. Various Telegram groups dedicated to government job preparation were putting out news of allegedly leaked papers. “I cannot believe this,” he says, distraught, imagining that a re-exam may be called. “I was sure of clearing the exam. I need to get a job this year; my family cannot survive otherwise.”

Population explosion

For three days, thousands thronged the nine platforms of Charbagh, Lucknow’s main railway station located in the heart of U.P.’s capital, 3 km away from Hazratganj, the city’s shopping hub. Trains leaving the station or coming in were bursting at the seams, with U.P. constable aspirants travelling even on the footboards. Scenes from the platforms went viral, with no place to sit, and as trains entered, it was difficult to find even foot space. The few dozen phone charging spots were almost impossible to access.

More than 2 lakh candidates were allocated test centres in Lucknow. “I let four trains go before boarding the Kaifiyaat Express from my hometown Azamgarh to reach Lucknow on February 17, but I still had to travel in the train lavatory,” says Rahul Maurya, 22, who took online coaching for the test.

Sensing the massive influx of candidates, U.P. State Road Transport Corporation had deputed 50 buses between the railway station and examination centres. Similarly, in Prayagraj, 100 buses were put to service. Other districts too tried to make arrangements, but the numbers were so high, cities and towns were overtaken by crowds.

The Railways also ran additional trains with added stops, and established help desks at major stations. “Despite the massive influx of candidates, no untoward incident was reported in our zone,” says Pankaj Singh, the chief public relations officer, North Eastern Railway.

Most aspirants who came from distances over 250 km and couldn’t make it back home the same day, spent the night at the railway station or bus stands. Autorickshaw drivers, sensing an opportunity with out-of-towners, pushed rates up to double.

Selection and success

The written test consisted of 150 questions of two marks each, divided into four sections: general studies, Hindi, numerical and mental ability, and reasoning. The Uttar Pradesh Police Recruitment and Promotion Board (UPPRPB), the recruiting agency, will now shortlist candidates for the Physical Standard Test. Here, physical requirements like height (the minimum for men is 168 cm; for women 152 cm); chest measurement for men (79 cm without expansion, 84 cm with expansion); and weight for women (minimum 40 kg) are assessed. Candidates will also take a physical efficiency test, where men will run 4.8 km in 25 minutes and women 2.4 km in 14 minutes.

New entrants are paid ₹21,700 a month, in addition to government benefits like free healthcare. Like most others, Maurya’s dream is to leave behind a life of poverty. “I hope to get a stable income and an improved social status. I am a graduate in Hindi, and in the private sector I will get informal and poorly-paid jobs,” he says. His father is a marginal farmer with 3 acres. Many of the candidates hail either from farming families fighting to make ends meet or from those doing physical labour of other kinds.

For someone selected at the constable position, a rise to inspector may take 25 years. “The first two years is a probation period. It takes 8-10 years to be promoted to head constable, and the same duration for promotion to sub-inspector (SI),” says Manoj Singh, in the U.P. police, adding that constables are the backbone of the force. “We are the first to reach a site. It’s also part of my job to maintain ties with local informers.”

Paper leaks and panic

On February 17, social media was rife with claims that the U.P. police constable exam paper had been leaked. Amitabh Thakur, a former Indian Police Service officer and now a politician leading the Azad Adhikar Party, claimed Milind Singh, an Azamgarh-based Bharatiya Janata Party leader, spoke of this on X (formerly Twitter) on February 18, at 9.04 a.m., saying the paper was being circulated since 7 a.m. “I also informed the U.P. government about malpractices at a centre in Meerut, but without any investigation, within minutes, the police replied on X that my claim was misleading,” Thakur says.

The government denied the paper leak charges. The UPPRPB formed an internal committee led by its Additional Director General, Ashok Kumar Singh, to assess the process of improvements, if required, for future recruitments. Renuka Mishra, the chairperson of the board, said there would be an “attempt to verify the unverified claims being made on social media after the examination is completed”.

The police detained more than 200 people for alleged cheating or fraud. “We caught a gang that took ₹20,000-₹25,000 from each candidate before the exam, claiming to deposit their education certificates. They would demand ₹10-12 lakh if a person was selected,” says Suraj Kumar Rai, Deputy Commissioner of Police, Agra.

The job market

“I spent three years in Allahabad preparing for various government jobs, including this one,” says Sachin Tripathi, an aspirant from Prayagraj district. Sanjay Singh Parihar, director of Mission Institute, a coaching centre in Prayagraj, who has been training aspirants for two decades, says many prepare for several exams in the Group-C and Group-D levels, including junior clerks. “They appear for multiple recruitment tests, and we train them for all,” he says.

Tripathi feels the paper leak “is like rubbing salt on our wounds; government vacancies are irregular and few”. The last time constable positions were opened in U.P. was six years ago, in 2018. The delay was attributed to the pandemic.

K. Srinivasa Rao, an economist with the Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow, says the three Ss of social security, stability, and salary, drive people to seek government jobs. Coaches attribute it to the economic realities of Uttar Pradesh, which had a per capita income of ₹70,792 in 2021-22, higher only than Bihar. “With lay-offs in the private sector during the COVID-19 pandemic, people realised the security of a government job,” says Parihar.

Last year, U.P. Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath had promised the youth over 2 crore jobs over a few years. Akhilesh Yadav, Samajwadi Party chief, had estimated on X that the assurance would mean about 13,700 jobs a day for the next four years. Data released by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy found that the State’s youth labour participation was plummeting, falling from 41.2% in the pre-pandemic period to 22.4% in September-December 2022.