New research has revealed genetic features that may signal the onset of multiple sclerosis (MS) long before a person shows symptoms of the disease, scientists say.

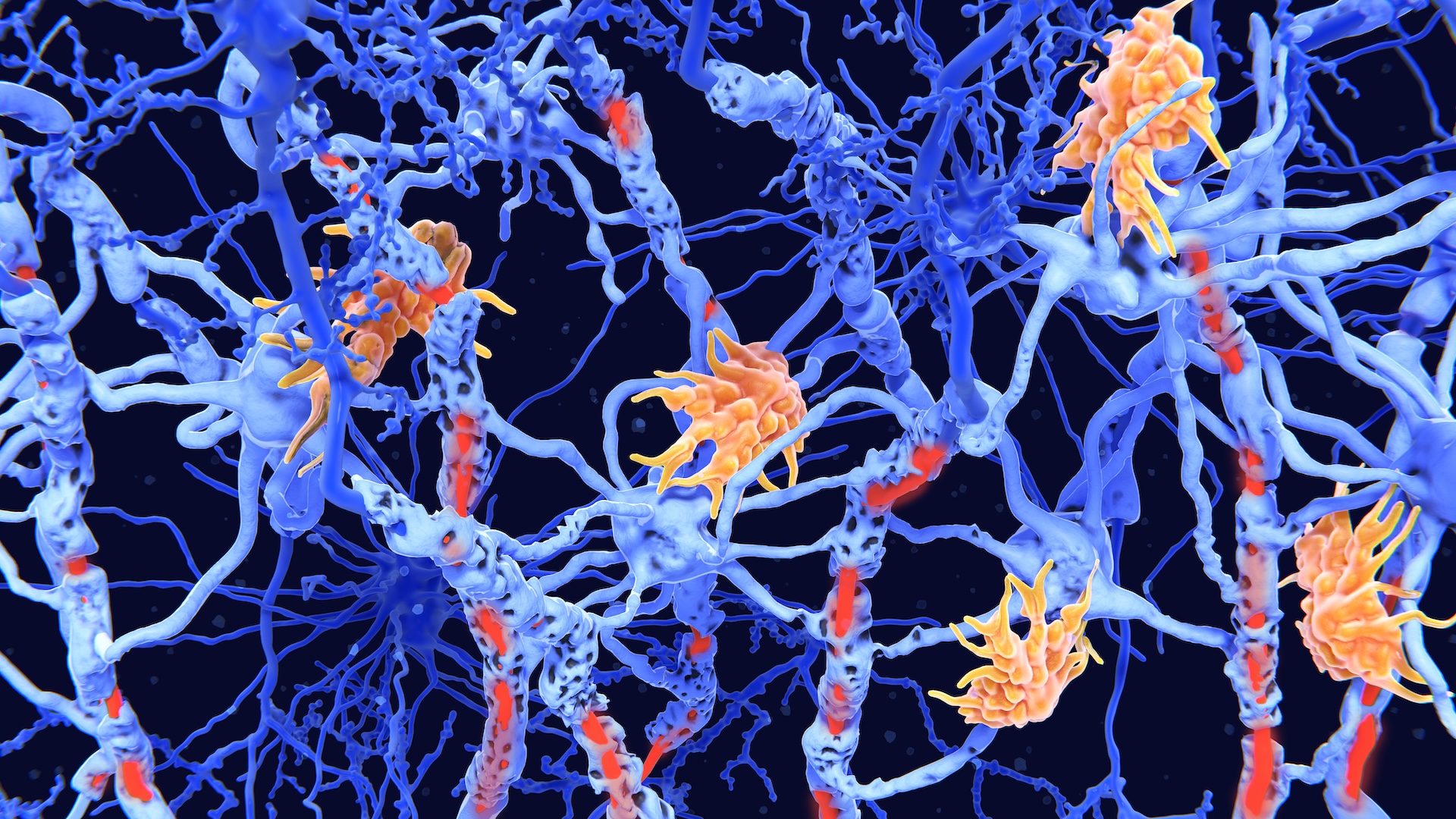

MS is an autoimmune disease that causes inflammation in the brain and spinal cord. This inflammation damages myelin sheaths — the insulation that encases nerve cells' long "wires" — and leads to symptoms of pain, fatigue, numbness or weakness, as well as problems with vision or movement.

People with MS are known to have high levels of immune cells called cytotoxic T cells, which normally help kill cancer and cells infected by germs. In MS, however, these cells accumulate in areas with visible myelin damage, but the role the cells play in the disease has remained largely a mystery — until now.

In a study published Sept. 27 in the journal Science Immunology, researchers studied the T cells of 12 pairs of identical twins. In each pair, one twin had MS and the other did not. When one twin has MS, the second has about a 1 in 4 chance of developing the disease down the line. Thus, the second twin's T cells offer insight into the immune systems of people who are likely to eventually experience full-blown MS.

Related: Europeans' ancient ancestors passed down genes tied to multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's risk

"Today, we have very good treatments for MS," study author Dr. Lisa Ann Gerdes, a neuroimmunologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, told Live Science. But people can't be treated until they are diagnosed — and the risk factors, triggers and earliest signs of MS are not completely understood.

"The MS Twin Study gives us a unique chance to look at patients with a prodromal [very early] stage of the disease, which is not possible in a real-world setting," Gerdes said. "Normally, if a patient has symptoms, the immune system has already entered the brain, so we are too late to see the main players driving inflammation in the beginning."

Notably, six of the twins without MS did have some inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) that could be detected in tests but didn't yet cause any obvious symptoms.

The researchers looked at genes that were switched on in the twins' T cells by measuring RNA, a molecule that helps cells make proteins from DNA's blueprints. The analysis revealed that the T cells of people with either MS or CNS inflammation were more active, and triggered more immune signaling, than those in people with neither condition. In short, those T cells seemed especially reactive. The researchers also found more activation in genes that help keep T cells switched on.

The earlier we intervene in the process of inflammation and destruction of the nervous system, the greater the impact we have.

Dr. David Duncan, Hackensack Meridian Health

By categorizing the hyperactive genes by disease stage, the researchers showed that the genes involved in T cell activation were most prominent in people who had CNS inflammation, but not full-blown MS. People with MS had more gene activity tied to helping T cells survive, move around the body, and call other parts of the immune system to attack.

Overall, the more advanced a person's disease stage was, the more T cells they had that showed these genetic changes. This lends weight to the hypothesis that these T cells drive inflammation in MS.

"Over and over again, studies demonstrate to us that the earlier we intervene in the process of inflammation and destruction of the nervous system, the greater the impact we have on our patients' disability outcomes," said Dr. David Duncan, a neurologist at Hackensack Meridian Health who was not involved in the research.

"Having insight into the earliest indicators of MS may help us make a diagnosis and initiate therapy long before any significant neurologic damage can occur," he said.

To verify their findings, Gerdes and her colleagues went two steps further.

First, they analyzed T cells from another group of 17 people. Twelve had MS and the remaining five had a noninflammatory brain condition. In this group, people with MS had higher activation in genes associated with T cell activation, function and survival than the people who did not have MS.

Second, the researchers analyzed publicly available genetic data from more than 61,000 individual T cells sampled from brain tissue that had been damaged by MS. They looked to see which genes were overactive and found many of the same genes they had in their patient testing, along with others related to inflammation.

These analyses strengthen the findings, but even so, the researchers cautioned that their study included only a small number of people from similar backgrounds, especially in the twin cohort.

"It will be important to see these findings reproduced by other investigators and labs with larger sample sizes," Duncan told Live Science. "It's also important, as mentioned in the study, to evaluate other immune cell types that are involved in MS pathology."

Still, the researchers hope that understanding more about gene activity in the early stages of MS could lead to more accurate evaluations of who's at risk of MS, as well as faster diagnoses and more targeted treatments for the disease.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!