Voting in local body elections begins this weekend with hopes that competitive races will finally help councils turn a corner on waning turnout. Justin Hu reports on a crucial test for local government's civic engagement efforts.

Turnout in local elections is under scrutiny as postal ballots make their way to voters, with persistent concerns about faltering engagement in under-represented communities.

Political observers will closely watch the introduction of Māori wards in 32 local authorities — which have already brought in more competitive races for seats across the motu.

A law change in 2019 means this year's race will be the first where council chief executives are required to help "foster participation" during local elections.

Political scientists surveyed by Newsroom say they're hopeful that competitive mayoral races across New Zealand's largest cities will help drive turnout in this year's election. But they're concerned that longer-term solutions have been slow to progress.

These suggestions range from more civics education resourcing to pushing the Electoral Commission to play a more significant role in promoting local elections. This year, as in 2019, the commission only promoted voting enrolment before official campaigning began.

Other suggestions have included standardising electoral systems across the country and developing strategies for under-represented communities.

University of Otago politics professor Janine Hayward is worried about some councils' continuing use of the first-past-the-post.

"We've just got to have local government catching up with central government, which has been using a proportional representation system for over two decades and has a system that actually fairly represents how voters voted.”

Hayward says it is "essential" that local government moves to single-transferable vote — a preferential ranked-choice voting system that 11 councils used at the last local elections.

"It wouldn't be a magic solution, but we know when we look at the councils that have been using single-transferrable vote for a long time; that its boosted women's turnout, and it is also showing improvements for Māori representation."

The use of multiple systems in different areas created confusion in the last local elections, according to a select committee inquiry that recommended moving to a single electoral system for all local elections but held back on recommending a specific voting system.

“If you’re not using the postal system, then you don’t know where the post boxes are." – Julienne Molineaux, AUT

The Justice Select Committee also endorsed giving more responsibilities to the Electoral Commission to centralise the promotion of local elections. Additionally, it recommended the Government consider potentially centralising the running of local elections — a suggestion that submitters did not universally support.

Last year, Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta told Newsroom that electoral system reform would likely be off the table until 2024 – aside from Māori ward changes.

"Due to other priorities in the local government portfolio, such as Three Waters and resource management reform, a comprehensive review of the local electoral system is not a priority for Parliament this term," she said.

At the time, a Department of Internal Affairs briefing advised Mahuta that it could take up to two parliamentary terms to implement any significant structural changes.

Another year of postal voting

The declining number of post boxes across the country is another variable being watched in turnout figures as many voters go online to find their nearest voting place.

“If you’re not using the postal system, then you don’t know where the post boxes are,” says AUT political scientist Julienne Molineaux.

Over the past 15 years, NZ Post has seen an 84 percent drop in letters posted, with the state-owned enterprise decommissioning around half of its Auckland post boxes in the past decade. But the organisation says its analysis shows no correlation between dwindling “street receiver” numbers and voting turnout.

Twenty-two-year-old Logan Soole is one of the youngest local representatives in the country. The first-term Auckland local board member says postal voting can be a mystery to younger voters.

“For older generations, postal voting and posting are what they did,” he says. “But you need to take it to the people and make it accessible, and postal votes are just not it in 2022.”

As a result, this year, several local councils have ramped up their efforts to parachute non-postal drop-off boxes to catch voters where they already are.

In Wellington, electors can lodge their votes at any supermarket in the region. At the same time, Aucklanders will be able to vote at major train stations and ferry terminals – in addition to all Countdown supermarkets around the city.

Molineaux says the moves are good but that drop-boxes work best when they’re available throughout the entire two-week election period – rather than as one-off events.

She says councils can go further by staffing a few busy locations to help answer voter questions: “People should know they can go there anytime and there will be someone there who can help them.”

A trial to introduce advance booth voting was also recommended by the 2016 and 2019 select committee inquiries.

This would mean more opportunities for people to submit special votes, with Taituarā (Local Government Professionals Aotearoa) also recommending a law change that would explicitly allow polling sites to issue “replacement” ordinary votes. The change would permit booth voting in local elections to closely emulate advance voting during general elections.

Councils and local authorities have heavily pushed attempts at online voting in the past six years. But slated trials have been mired in security concerns from technologists and pessimism about its effect on voter turnout.

“We note that many countries that have trialled online voting in local elections no longer use this voting method,” the Justice Select Committee’s report stated. “In cases where convenient voting methods already existed, the evidence indicated that online voting had little or no effect.”

More broadly, many experts believe disengagement from politics is a more pressing long-term issue.

Will people vote if they’re not politically engaged?

In 2019’s local body elections, 42 percent of eligible voters overall turned out to vote nationwide.

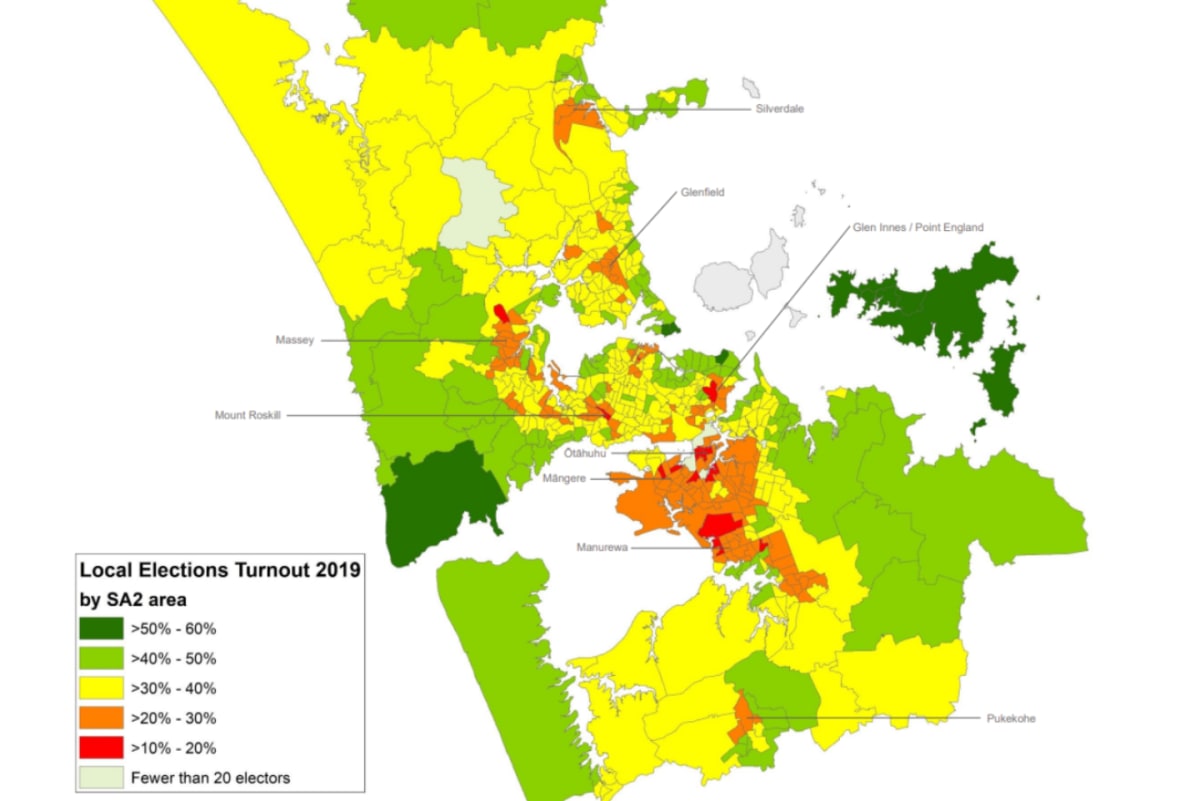

But Molineaux says the figure helps to mask stark inequalities within local communities.

Some rural councils like Kaikōura and Westland saw an overall turnout above 60 percent. Meanwhile, in Auckland, turnout dipped below 25 percent in parts of the city’s south, while overall turnout dropped to 35 percent.

"If we had a 40 percent turnout and that 40 percent represented the population in terms of demographics, socioeconomics, interests and values, then it wouldn't be such a bad thing," Molineaux says. "But when turnout falls, it falls unevenly.

"Young people don't vote as much as older people. And in local government, that gap is very wide. We know that people in neighbourhoods who have higher deprivation vote less. Meanwhile, we know that people who are homeowners are more likely."

“What we get is a skewed population voting, and that creates an incentive for candidates to pitch their policies at those voters and not the population as a whole.”

Hayward describes this as a “vicious cycle” where groups become left out of decision-making.

“It happens worldwide, it's not a New Zealand problem ... but policymakers’ views gets smaller and smaller, and groups get marginalised and disengage.”

Molineaux believes failed attempts to introduce online voting in 2016 and 2019 may have diverted resources from strategies to better engage with harder-to-reach communities.

“It can't be council coming in from the top with branding and slogans,” she says. “It needs to be driven by those grassroots organisations with good context.

“Pick a local board area with a really low turnout [in Auckland]. Let’s open an office in that area, employ some staff, make contact with local groups and schools, and establish relationships… it would've been interesting to do that over a six-year period.”

"You never know, but at the moment, with the number of young people and the kind of staunchness they have nowadays – I have no fear that they're going to shake things up." – Veisinia Maka, youth advocate

Youth advocate Veisinia Maka agrees and believes in a grassroots approach to empowering groups within Tāmaki Makaurau. Since 2017, Maka has been an Auckland Council's Youth Advisory Panel member and chaired two council-sponsored youth panels in Howick and Tāmaki.

“It’s the idea that we have our own autonomy, we know what we're doing, we know how to engage with our people, and this is how we're going to do it best,” she says. “I think Auckland Council has slowly recognised that they can't bear that burden”.

She refers to housing as an example of an issue where younger voters could be left trying to vote based on plans that are difficult to understand and required more civics education.

“Housing [as a national issue] is quite connected at a localised level, and I don't think young people fully understand … the connection there."

But Maka is hopeful when asked whether she is worried about a cycle of under-representation: "Over the past few years, I've seen the power of young people. Nowadays, young people are incredibly upfront, vocal, and straight to the point.

"You never know, but at the moment, with the number of young people and the kind of staunchness they have nowadays – I have no fear that they're going to shake things up."

Q&A: With voting for local elections set to begin on September 16, we asked Professor Janine Hayward about how, and why, you should vote.

What is your advice for voters?

Do your homework on who candidates are and what they stand for. Local media often publish summaries about candidates. Local Government New Zealand has provided a guide to what the candidates in your region stand for (https://policy.nz/2022). Whoever is elected will make important decisions that affect you and your community, so make sure you know what you are voting for.

How to vote out an incumbent

This depends on which electoral system you are using. If you are using FFP, you may need to consider a strategy to avoid splitting the vote amongst a like-minded majority of voters across a number of candidates and allowing a less popular candidate to be elected on a minority of the votes. If you are using STV, you need to think about which candidates you want to support and vote for them in the order of preference (1, 2, 3, etc). STV was designed to avoid splitting the vote in the way that FPP does in multimember elections.

Can you explain the Single Transferrable (STV) electoral system?

STV is a simple system to use. You are casting a single vote, which can transfer between candidates to ensure that it is not wasted. When you vote with STV, you rank the candidates you like, in order of preference starting with your favourite candidate (1) and then your next favourite (2) and so on. You can rank as many or as few candidates are you want to, depending on how many candidates you support.

Do voters need to rank every candidate?

You don’t need to rank all candidates. You only need to rank the candidates you want to support. If you rank a candidate, that may help them to get elected. So don’t rank them if you don’t rate them!

Can you explain the First Past the Post voting system?

To vote using First Past the Post, voters place a tick next to the name of the candidate(s) they wish to support. In elections where one member is being elected (such as a mayoral election), FPP does not require that a candidate wins a majority of the votes, just more votes than anyone else. In multi-member elections (such as council elections), voters cast multiple votes to (potentially) elect multiple candidates to represent.

In your opinion, which system is better and why?

No electoral system is perfect, and both FPP and STV have strengths and weaknesses.

However, in relation to New Zealand’s local government elections, FPP is not an effective electoral system to use in multi-member elections such as council elections because it does not do a good job of translating the preferences of the broad community of voters into who gets elected. In FPP elections, it is possible for a minority of voters to determine the election of a majority of the candidates elected. Likewise, in mayoral elections, it is possible for a mayor to be elected by a minority of voters.

STV was designed specifically to overcome the short-comings of using FPP in multi-member elections such as our council elections. It is a proportional representation system, so it does a much better job than FPP of ensuing that the way the community voted is reflected in the candidates who get elected. In mayoral elections, it ensures that the winning candidate has received a majority of the votes.

Why is it important for people to vote?

It is important to vote in the upcoming local elections because the people who get elected will make decisions that directly impact on your life. So make sure you have a say in who that is by casting a vote.