Istanbul, Turkey – In the aftermath of Turkey’s dramatic elections, a new name is on the lips of political commentators: third-placed presidential contender Sinan Ogan.

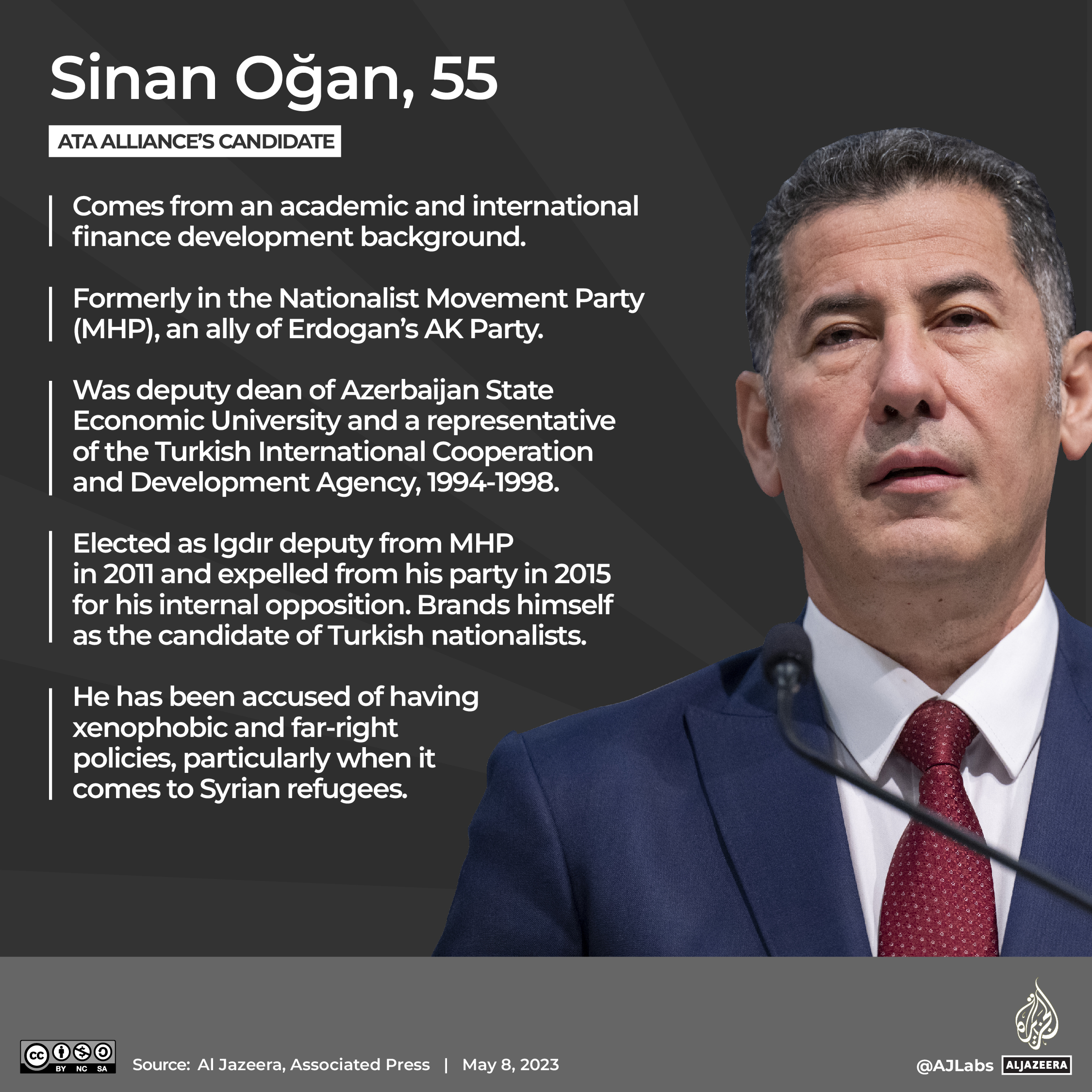

The nationalist candidate, backed by the ATA Alliance, secured 5.17 percent of the vote. The support of those voters will be vital as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, 69, and opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu, 74, head to a second round on May 28 because neither crossed the 50-percent mark needed for an outright win.

The coming two weeks will see discussions between Ogan’s team and the two remaining contenders.

“At the moment, we are not saying we will support this or that [candidate],” said Ogan, 55, early on Monday. “Those who do not distance themselves from terrorism should not come to us.”

“It seemed from the very beginning that the elections would go to the second round, and Turkish nationalists and Kemalists will be the ones who determine the second round,” he said.

Ogan’s reference to “terrorism” is a vital one. In the eyes of Turkish nationalists, both Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu have the support of those they consider aligned with terror groups.

Kilicdaroglu’s candidacy was backed by the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), which stems from Turkey’s wider Kurdish movement and is considered a political bedfellow of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) by nationalists such as Ogan.

The PKK has waged a 39-year campaign against the Turkish state, which has led to tens of thousands of deaths. It is listed as a terror organisation by Turkey, the United States and the European Union.

Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AK Party), meanwhile, received support from Huda-Par, a predominantly Kurdish political Islamist party. Three Huda-Par politicians have been elected to parliament by being included in the AK Party’s candidate lists.

Huda-Par has historic links to Hezbollah, a Kurdish group that waged a brutal campaign of violence in the 1990s as it fought the PKK and targeted Turkish police officers. The group has no connection to its Lebanese namesake.

Who will he endorse?

“Ogan was clear from day one – he said he would support the side that distances itself from terrorism,” said Murat Yildiz, a former adviser for the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) who worked alongside Ogan when he was also a member of the MHP.

“He will ask Kilicdaroglu for promises that he won’t collaborate with HDP on some issues,” Yildiz said. “It will be difficult to discuss this with Erdogan because Erdogan has aligned with Huda-Par and there are three deputies from Huda-Par now.”

Berk Esen, a political scientist at Istanbul’s Sabanci University, said splits between Kilicdaroglu and the nationalist Iyi Party, the second-largest party in his opposition Nation Alliance, turned nationalist voters away from his candidacy.

“Many swing voters went for Sinan Ogan, partly because of the nationalist card but partly because he was a ‘none of the above’ candidate,” Esen said.

“A small constituency in this country does not particularly like Erdogan but is also very distant from the pro-Kurdish movement and finds Kilicdaroglu to be a weak leader,” he said. “Ogan recruited those voters.”

“Many of them are Turkish nationalist voters who are not really sold by messages from either side because Erdogan is allied with Huda-Par, a Kurdish Islamist party, and Kilicdaroglu was seen as having a too cosy relationship with the Kurdish [HDP] opposition,” Esen said.

Convincing his own voters

It also remains to be seen whether Ogan’s supporters would vote with him in the run-off.

“Even if he agrees with Kilicdaroglu, he has to convince his own voters, and we don’t know how loyal they are to him,” Yildiz said.

Ogan, an academic with a background working for think tanks, entered politics with the MHP, which is now allied with the AK Party in the People’s Alliance. He served a term as an MHP parliamentary deputy from 2011 to 2015 for his home province Igdir, which lies on Turkey’s eastern border.

“He’s a calm guy, straightforward,” Yildiz said. “Since his early political career, he always aimed for the leadership of the MHP. He was the crown prince to [MHP leader Devlet] Bahceli and had a good relationship with him.”

“But as his popularity increased, Bahceli started to see him as a threat,” Yildiz said. “They slowly started to fall apart. Ogan has a certain ego, which Bahceli also didn’t like.”

The mid-2010s were a turbulent time for the MHP with senior party members challenging Bahceli, partly due to his growing closeness to Erdogan. This led to Ogan being expelled from the party in 2017 along with Meral Aksener and Umit Ozdag.

Aksener and Ozdag went on to form the Iyi Party. Ozdag was dismissed from the Iyi Party in 2020 and founded the anti-migrant Zafer Party a year later. The Zafer Party is the driving force of the ATA Alliance, which backs Ogan although he is not a member.

It is Ogan’s commitment to the MHP – which performed unexpectedly well in Sunday’s vote, taking more than 10 percent – that has stopped him from joining or founding another party.

“When Aksener and Ozdag founded the Iyi Party, Ogan refused,” Yildiz said. “He said, ‘I was born MHP, and I will remain MHP.'”

“Everything he’s doing now should be seen in this context. Even his candidacy for the presidency is another move to become the leader of the MHP.”