Since 2021, about 15,000 Haitians have found new lives in Springfield, Ohio, after fleeing the violence of Haiti, their native country.

But a wave of baseless rumors and hate, amplified by former President Donald Trump and his running mate, U.S. Sen. JD Vance, has shattered that sense of safety. Many of the city’s Haitian immigrants are left questioning whether their vision of an American dream is still possible.

Frightened and worried, many Haitians say they are fearful of going outside and staying in Springfield.

The morning after the presidential debate, a Haitian woman who had moved to Springfield six years ago told a newspaper reporter that “they’re attacking us in every way.”

In addition to the anxiety, the woman, who asked not to be identified, said that her car windows had been broken in the middle of the night. “I’m going to have to move because this area is no longer good for me,” the woman said. “I can’t even leave my house to go to Walmart. I’m anxious and scared.”

Trump’s inflammatory statements, which have included wrongful allegations of Haitians eating pets, are part of a broader historical pattern of racism and anti-Black xenophobia in the U.S. aimed at Haitians. Days after the debate, Trump further explained how he would start his mass deportation program in Springfield. “Illegal Haitian migrants have descended upon a town of 58,000 people, destroying their way of life,” Trump said.

The comments have not only stoked existing racial tensions but have also sparked racist discourse and violent threats against Haitians across the country.

As a scholar of migration who has studied Haitian immigrants in the U.S. for over 25 years, I have seen how Haitians, as Black immigrants, are doubly marginalized, by not only the structural racism embedded in U.S. immigration policies but also the broader societal racism experienced by Black Americans.

In my view, Trump’s baseless allegations reflect America’s deeply rooted history of systemic racism against Haiti and its people.

A flawed history

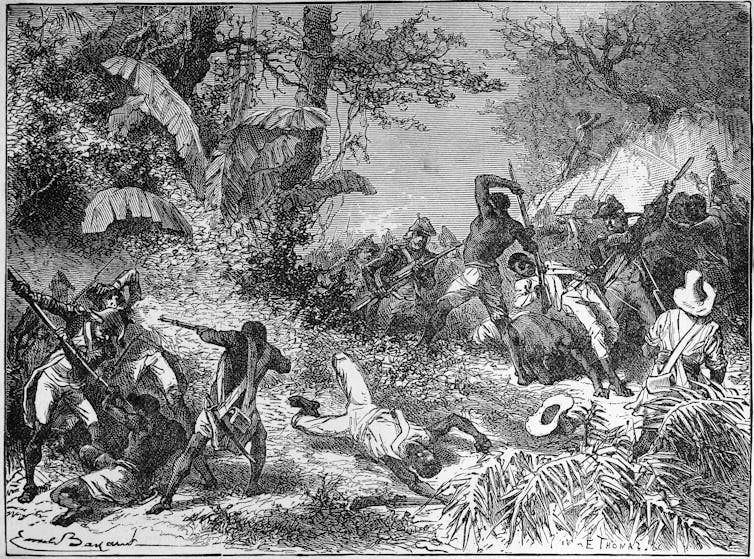

The roots of anti-Haitian racism in the U.S. can be traced to the Haitian Revolution in 1804 in which Black Haitians who were enslaved rose up and overthrew the French colonial government.

Haiti became the first independent Black republic in the world, and the country’s independence terrified many in the U.S., especially white slaveholders. They feared the revolution might inspire slave revolts at home.

For much of the 19th century, the U.S. refused to recognize Haiti as a legitimate nation. It wasn’t until 1862, during the Civil War, that the U.S. finally established diplomatic relations with the country.

But the U.S. continued to exploit Haiti for its own economic and military interests, occupying the country with the military from 1915 to 1934. During this period, the U.S. controlled Haiti’s government and finances, installed a pro-American president and helped establish a brutal military force.

The occupation worsened racial and economic inequality in Haiti and further destabilized the nation.

This history of exploitation and interference has had long-lasting effects on Haiti’s ability to develop economically and politically, a situation exacerbated by continued U.S. intervention throughout the Cold War era.

During the nearly 30-year dictatorships of François “Papa Doc” and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier between 1957 and 1986, for example, the U.S. government provided approximately US$900 million in financial support to these repressive regimes, despite their notorious human-rights abuses.

Anti-Black immigration policies

All the history of U.S. involvement in Haiti set the stage for the mass migration of Haitians to the U.S. since the early 1960s.

Over the years, about 200,000 Haitians have sought to escape violence and poverty to the U.S.

Those with resources, such as the Haitian elite and middle class, migrated legally, settling in New York and Miami. Many of them organized ways to send aid to Haiti and brought attention to human-rights abuses being committed by the Duvalier regimes.

Poor Haitians soon followed, arriving by crude boats.

In September 1963, the first boatload of Haitian refugees landed in Miami. But instead of finding freedom, all 23 Haitians were denied asylum and sent back to Haiti by the U.S. immigration authorities.

Since then, Haitians arriving by boat have faced arrest, detention, asylum denials and deportation as successive U.S. governments refused to recognize the political repression in Haiti. Instead, Haitians were labeled economic migrants who sought a better standard of living and, as such, were not eligible for asylum.

From 1981 to 1991, for instance, 433 boats carrying approximately 25,580 Haitians were intercepted by U.S. immigration authorities. Only 28 people were allowed to pursue refugee claims.

The Haitian experience in the US

Often portrayed by white policymakers as disease carriers and criminals, Haitian immigrants have long suffered discrimination and dehumanization in the U.S.

In the 1980s, during the HIV crisis, U.S. health officials wrongly labeled Haitians as high-risk carriers of the virus, reinforcing harmful racial and ethnic stereotypes.

Despite a lack of scientific evidence, Haitians were stigmatized as a group, leading to economic and social exclusion within the U.S. Many Haitians lost jobs, housing and faced threats of violence simply because of their nationality and ethnicity.

My research has shown this portrayal of Haitians as dangerous and undesirable persists today, as reflected in Trump’s and Vance’s recent claims. The narrative of immigrants eating pets and spreading diseases is a recycled trope in American history, used by white conservative politicians to stoke fears about foreigners to reinforce white supremacy.

Historically, these kinds of claims have been used to justify exclusionary immigration policies and racial violence against nonwhite populations.

The accusations against Haitians in Springfield have not only triggered immediate threats of violence but have also reinforced deep-seated, anti-Black xenophobia that continues to plague U.S. society.

In recent years, hate speech and attacks against Black immigrants, including Haitians, have been on the rise. Black immigrants, regardless of their legal status, face higher rates of deportation and are more likely to be targeted than white immigrants by law enforcement.

Addressing anti-Haitian racism

The allegations made by Trump and Vance represent a dangerous escalation of rhetoric that has real-life consequences for Haitians in the U.S.

The demonization of Haitians in Springfield is not just a political ploy – it is part of a broader strategy to uphold systems of exclusion that have historically been used to marginalize Black people, both immigrants and citizens.

Thurka Sangaramoorthy receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.