Where does great writing come from? How does the reading of writers shape their work? Perhaps the great writers are true originals, free from influence?

For many readers of Elena Ferrante’s celebrated novels of the relationships between girls and women, her stories are so distinctive they appear to have arrived fully formed. In the essays collected in her latest book, though, she offers a compelling account of the vital role her reading has played in the creation of her work.

Review: In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing – Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein (Europa)

Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym; the author’s true identity is unknown. And there is a connection between her anonymity throughout her long career – even as the Neapolitan novels brought her international fame – and the way she regards her inheritance from literature. This singular writer associates her anonymity with a refusal to promote the individual writer to “protagonist”.

During a rare in-person interview with her publishers, Ferrante argued against the media’s “demand for self-promotion”. All literature, she said, is the product of tradition:

a sort of collective intelligence. We wrongfully diminish this intelligence when we insist on there being a single protagonist behind every work of art.

In the Margins, a collection of four essays on a life of reading and writing, makes clear the complex debt to literature that Ferrante and all writers owe, no matter how distinctive and celebrated they might be. Together the essays offer a fascinating commentary on coming to writing through reading. Importantly, they show how a restless critique of one’s reading and writing can add fuel to the fire.

Writing inside the margins

The first essay, “Pain and Pen”, describes the young Ferrante’s first attempts to write and sets up the major theme of the book: the struggle between two kinds of writing.

At school, learning to write in her notebook, Ferrante was taught to write neatly, within the red margins of the page, often encountering punishment for straying over the right-hand line. From then on, she felt both a sense of danger when she strayed too close to the margin and a curtailment when her writing remained neatly within the red margins:

I believe that the sense I have of writing – and all the struggles it involves – has to do with the satisfaction of staying beautifully within the margins and, at the same time, with the impression of loss, of waste, because of that success.

Ferrante’s novels, we come to understand, emerge from a battle between form and wildness.

The female pen

A parallel struggle arises for the young writer between what she reads – what has been decreed literature – and what she might write, from her own imperfect self.

For a young woman, there is an extra degree of difficulty. “I read a lot,” Ferrante says of her youth, “but what I liked was almost always written by men.”

She tried unsatisfactorily to imitate the “male voice” in her head. By the end of her adolescence, that male voice had left Ferrante believing that

Not only was writing difficult but I was a girl and so would never be able to write books like those great writers.

Literature is intimidating and excluding, but it will also articulate for Ferrante the nature of the problem and suggest solutions. Towards the end of high school, she tells us, “completely by chance I came across the Rime of Gaspara Stampa”.

Stampa, the great female poet of the Renaissance, used her pain in love to inspire her pen, wishing to draw from within

her own “human flesh”, a garment of words sewn with a pain of her own and a pen of her own.

Across the centuries, Stampa’s writing passes on its message:

the female pen, precisely because it is unexpected within the female tradition, had to make an enormous, courageous effort.

Several times in these essays, books arrive in Ferrante’s hands like a divine gift, offering just what she needs. Messages appear in chance readings, re-readings and re-evaluations of Emily Dickinson, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf and others.

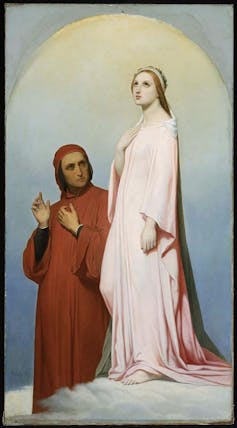

She learns that writing requires deep courage, that the small “I” of a woman might link herself to history, that women can tell their own and each other’s stories. In Dante, she sees Beatrice speak with wisdom and authority, and it spurs her on.

Read more: Guide to the Classics: Dante’s Divine Comedy

True writing is tempting fate

The books appear when the writer needs them, as if by magic, but it is clear that in Ferrante they find a hungry and perceptive reader, alert to the lessons of reading, ready to absorb what the young writer needs.

Writing, like reading, requires this kind of alertness to the gifts of chance. Ferrante portrays the writer as a patient being, keeping an eye out in the work for the spark of something alive that will capture the chaotic energy of the world.

“It’s one thing,” Ferrante writes,

to plan a story and execute it well, another is that completely aleatoric writing, no less active than the world it tries to order.

Alea in “aleatoric” is from the Latin for dice. The writer throws the dice and must be ready to follow where they lead her.

Reading the diaries of Virginia Woolf, Ferrante finds an image for the “true writing” she seeks. Woolf records a conversation with Lytton Strachey, in which she says that writing fiction is like rummaging in a bran pie. She is “twenty people” when she does this, and she does not know what will come out.

Writing, Ferrante reads from this, “is a pure tempting of fate”. It

doesn’t pass through the sieve of a singular I, solidly planted in everyday life, but is twenty people, that is, a number thrown out there to say: when I write, not even I know who I am.

She waits for “other I’s” to pull her beyond the margins, to take her

where I’m afraid to go, where it hurts me to go, where, if I go too far, I won’t necessarily know how to get back.

Read more: Guide to the classics: A Room of One's Own, Virginia Woolf's feminist call to arms

Frantamuglia

It is easy to recognise here the novelist of the perilous emotional territory between girls and women, of the truths that others would be afraid to speak aloud. Ferrante understands that the work is to wait

patiently to start writing with all the truth I’m capable of, destabilizing, deforming, to make space for myself with my whole body. For me true writing is that: not an elegant, studied gesture but a convulsive act.

The truth of this writing comes from the subconscious. It is a “slip up” of the mind that draws on frantamuglia, what Ferrante’s mother called her internal terror: “a whirlpool of fragment-words … the debris from a land submerged by the fury of the waters”.

It is much more appealing to remain within the margins, to be a writer who orders the world “into neat narratives”, than to venture into this frightening territory. Yet Ferrante knows

that the pages that finally persuade me to publish books come from there … beneath the order is an enduring energy that will stumble, disarrange …

Frantamuglia is also the title of a collection of Ferrante’s thoughts, letters and interviews published in 2016, soon after journalist Claudio Gatti published an article attempting to reveal her identity in the New York Review of Books. The collection and the term stand as firm resistance to attempts to limit existence to the fully ordered and known.

The difficulty of storytelling

The perhaps inevitable result of the tension between order and some disarranging force is an increasing dissatisfaction with the realist form, with its pretence that the world leaves the imprint of truth on the page without an intermediary.

Ferrante becomes attuned to stories that illuminate the slipperiness of storytelling: “books that discuss how difficult it is to tell a story and yet intensify the desire to do it”.

This becomes a lifelong obsession. In a recent correspondence with the novelist Elizabeth Strout, Ferrante states that she particularly admires Strout’s novel My Name is Lucy Barton (2016) for the protagonist’s status as a writer and for its attention to the difficulties of saying, in writing, how something really was. Ferrante explains that she has a special shelf in her library for books that centre the problems of writing, and that My Name is Lucy Barton sits upon it.

We recognise Ferrante’s characters in such statements, the ways in which they make fierce attempts to narrate their lives. And we can very much see the author in the following, which Ferrante wrote in her notebook as a teenager:

The writer has a duty to put into words the shoves he gives and those he receives from others.

If “he” were replaced by “she”, Ferrante might be talking about any of her novels.

The freedom of the cage

Finally, the young Ferrante writes a book that doesn’t “seem too bad”. She develops a plan to send it to a publisher with a letter explaining the story’s origins and influences. What she will write in this letter seems clear to her. She describes the real people and places from which she began, and the distortions it has been necessary to apply, as well as the novels that have inspired her writing.

As she goes on, however, the truth of the letter becomes complicated. She sees her “urge to exaggerate defects, minimize virtues, and vice versa”. There is an inkling, too,

of what I could have written in that book but that would have hurt me to write, and so I hadn’t done it.

Ferrante gives up on the endeavour, but over the years she makes important discoveries: about writing in the first person, about realism as a “repertory of tricks”, about the centrality of the narrator, about the inability of literature to order the “whirlpool of debris”. She credits these discoveries to the attempt to write that letter.

That letter and its dormant lessons might be considered an “exegesis”. An exegesis is a critical interpretation of a text, originally of scripture. It has become a genre of assessment within the study of creative expression. Students of creative writing, art and music, for example, will produce a piece and provide an accompanying exegesis.

An exegesis can be difficult to write, as the letter was for Ferrante. It is trying to get at an elusive kind of truth. How was the thing made? Where did it come from?

The exegesis forms a kind of partner to the art, as reading is to writing. It responds to and helps to create the artwork dynamically. The discoveries made in writing the exegesis, in considering what has been learned in trying to make the art, should help to develop the art further. Ferrante’s letter and these essays are stunning examples of this mode in practice over a life’s work.

The significance of exegesis arises from the importance of critical reading. All writers do the work of exegesis, even if they don’t try to write down the process. They interact with what they read, working through admiration and dissatisfaction. A writer I admire tells only a part of the truth – what can I make of that?

In these essays, Ferrante tells a gripping story of how the writing self is made by reading, of how literature is writing that both admires and is dissatisfied with the forms that it has been given.

“I’ve never stopped believing in the importance of the writing we’ve inherited, which the ‘I’ who writes … is made of,” Ferrante tells us.

The challenge, I thought and think, is to learn to use with freedom the cage we’re shut up in.

Belinda Castles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.