Maybe you’ve seen The Thing About Pam, the recent NBC black comedy starring Renee Zellwegger as convicted killer Pam Hupp – and you devoured it in one binge-session. Or maybe you watched it week to week, reading reviews of how much time Zellwegger spent in the makeup chair.

But you probably didn’t know that a detective who worked on the actual Hupp case thought the show was “despicable," misrepresentative of the case, the witnesses, the investigation, and everything else.

The true crime phenomenon shows no sign of slowing down – as documentaries, podcasts, dramatizations and all manner of content continue to explode across platforms – and the reaction of that Hupp detective is not unusual. Armchair sleuths may spend countless hours poring over the lives of crime victims while concocting their own theories, but family members, investigators, victims themselves and even offenders frequently bristle when they see portrayals of their own lives.

Why are we so fascinated by gory tales of death, murder and mayhem? And is the public’s bombardment with true crime content helping or hurting?

The fascination, at least, is nothing new.

Adam Golub, an American studies professor at California State University, has devoted much of his research to studying the concept of the “monster next door, the monster, the anonymous monster in the city.”

“These are not new phenomenon,” he tells The Independent, pointing to the rise of mass media and tabloids in the 1800s, “when you see this kind of emerging fascination with trials and with criminals, and newspapers started hiring crime reporters for the first time. And they would keep a single crime on the front page of the newspaper for weeks, because it sold issues.”

And there are reasons for that.

“Monsters remind us of what’s very different, versus what’s supposedly normal and human,” he says; in the same way, true crime can serve as a “reminder about evil and human behavior in a criminal context” while teaching people to look for “red flags … what to look out for in a sociopath in the making.”

Streaming platforms have provided a perfect conduit for those good-and-evil examinations in the form of reality and dramatized true crime - available all the time at the touch of a finger.

Netflix originally introduced streaming in 2007 and debuted its first inhouse-produced programming in 2013; that show, House of Cards, exploded in popularity. While not true crime, its success -- and the spotlight it shone on the appeal of binge-watching a series -- helped open the coffers for Netflix-produced true crime content to come.

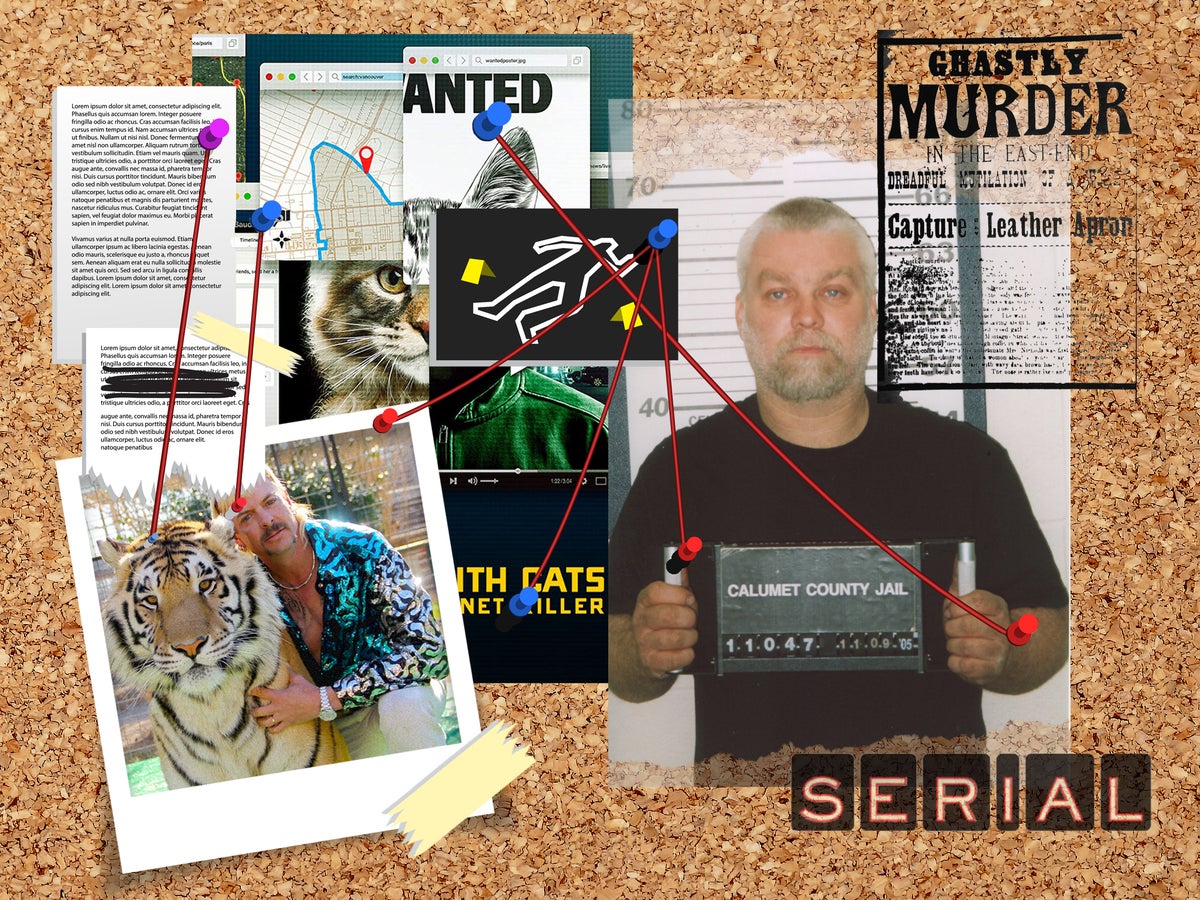

One year later, the podcast Serial debuted, raising questions about the 1999 murder of Maryland teenager Hae Min Lee. A year after that, Netflix released Making a Murderer, which chronicles the prosecution of two men for the murder of 25-year-old photographer Teresa Halbach. It became the water cooler conversation topic at the end of 2015, not only in the US but then internationally.

When Covid hit, the pandemic coincided perfectly with Netflix’s release of Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness and fed into lockdown boredom and fear as well as the rising true crime trend.

A large part of the mass appeal of true crime,Mr Golub emphasises, is the “immediacy” and “accessibility” in how it’s packaged.

“You can kind of curate and customize to … the rhythms of your everyday life,” Mr Golub says, adding that “ people who previously had maybe a kind of tangential interest in true crime, or a kind of little curiosity in it, suddenly, they can immerse themselves in it.”

Who among us hasn’t sat down with a meal in front of Netflix to learn about the grisly murder of a young woman?

Forensic psychology practitioner Laura Brand, a serial killer expert who’s forged relationships with dozens of mass killers on death row, remembers the true crime obsession starting even earlier than Serial and Netflix. She recalled when everyone from students to housewives became hooked on the TV series, Criminal Minds.

That started in 2006 and, in her mind, began the more mainstream fascination with true crime. When she was a student 20 years ago, she remembers her interest in true crime being completely abnormal.

“Back when I was in high school or college, I was always the weirdo, you know, reading about this stuff and studying it ... to go even find these books, I had to go to the back of the bookstore – like it was always on the back wall. And now I go into, like, Barnes & Noble, and it’s front and centre.”

While she’s surprised by the mainstream explosion, she agrees with many of Mr Golub’s points about the seemingly hardwired human interest in true crime.

Like Mr Golub, she believes many true crime enthusiasts connect to the content as a way to learn and protect themselves.

“This stuff speaks to us primally,” she says, adding: “Knowledge is power. So the more we study it, the more we learn about it, we feel safer, we feel more security, like hyper-vigilant against it ... it taps into that primal sense of survival.”

She adds: “By watching the true crimes, I think we get a sense of that ... we feel more empowered and feel more safe by watching it and listening to it.”

For those reasons, viewers might feel comforted and educated by true crime content. But so will current or would-be offenders, according to serial killers themselves.

The ones who spoke to The Independent and Ms Brand about true crime popularity from death row, where media access is severely limited and the extent of the phenomenon has yet to permeate the prison walls, were shocked at public interest in the most gruesome of atrocities. But they issued dire warnings.

“What I can tell you is that there are twice as many serial killers on the street nowadays because these are already smart guys, and now they are watching it and learning and getting smarter and smarter on how to cover their tracks, hide bodies, all of it,” says Wayne Adam Ford, a long-haul trucker on death row in San Quentin after killing at least four known victims.

“But you’ll never find them because of how forensically savvy they have gotten from all the shows and such. But trust and believe there are twice as many out there now than there ever was in history.”

Another San Quentin inmate, who asked to remain anonymous, tells The Independent in a phone conversation, with no trace of irony: “I am concerned that we are growing narcissistic and psychopathic.”

All of the true crime content, he says – whether demonizing or mythologizing offenders – is leading to a “social level [that] is more accepting of it ... because of the turning of the human psyche.

“I think we’re more selfish. I think everyone’s more criminally inclined, therefore, it’s more acceptable by everyone ... I think the lack of right and wrong and fusing the human consciousness without the concept of good and evil is producing a desperation for fame, because there is no satisfaction in good behaviour in and of itself anymore.”

And true crime content isn’t just proliferated across TV shows, streaming series or documentaries; now platforms such as TikTok, YouTube and Reddit have taken up the armchair detective angles, leading to an entirely new spinoff of the genre.

Sarah Turney, whose older sister vanished in 2001, had turned to such channels to promote her sister’s case. So did Julie Murray, whose younger sister, Maura, has been missing for 18 years.

Both sisters-turned-advocates saw the potential of using the internet to find their disappeared siblings. They soon recognised it as a “double-edged” sword, Ms Murray says; without control of the narrative, their family stories were commandeered in unimaginable and hurtful ways.

“It’s become people’s pastime,” Ms Murray tells The Independent. “I mean, there’s people out there that do this case on Reddit or wherever, other forums, all day and all night.It’s a dark obsession, and it’s exploitative ... there’s no bounds to what they say, nothing is off limits. I mean, Maura has been completely humiliated and dehumanized all over the internet, and her 21-year-old decision-making skills have been plastered all over the internet.

She says her sister has become “voiceless,” prompting her own efforts to speak in Maura’s absence - including about the ethics of true crime content and “the victims and families left behind in the wake of these tragedies.”

She says families such as hers are retraumatized when cases are treated as entertainment.

“And so it’s like trauma piled on top of trauma ... it’s at a point where the true crime community is just ruthless, and they sideline ethics for dramatic effects, and everything is sensationalized.

Ms Turney began her own podcast three years ago, from the closet of her suburban Phoenix home. She’d felt revictimized by both law enforcement and true crime content producers - the latter looking to seize upon family tragedy, she believed, to manipulate narratives while riding the wave of the true crime pop culture phenomenon.

Her podcast, Voices for Justice, features unsolved missing persons cases; families come to her every day looking for help and publicity to find their loved ones, she says.

“So I like to call my podcast, basically, true crime with a purpose; true crime with a call to action. Every episode of my podcast does end with a call to action, and that comes usually directly from families says Ms Turney, who has a unique perspective as a podcaster herself while also a relative of a victim.

Gil Carrillo, one of the detectives who helped solve the Night Stalker case – for which Richard Ramirez was sentenced to death – says he never facilitates contact with victim families while participating in productions.

“Any time I’m asked to do a documentary, the first thing I tell them ... is: I will not assist you in contacting one victim or witness. You do that on your own. It’s up to them.”

Filmmaker Bobby Kennedy III – grandson of Robert F. Kennedy and scion of a family that has been under a microscope since well before his birth 37 years ago – comes to the true crime discussion with another unique vantage point.

Countless members of his family have been endlessly dissected for decades by all manner of documentarians and theorists, and Mr Kennedy himself has looked to historical material for films.

“I think a lot of the cool thing about the true crime genre, in general, is, like, a lot of those people ... the Reddit Bureau of Investigation, or whatever you want to call them, they occasionally crack cases,” he says. “So you can’t say that the obsession hasn’t gotten us to cool places.”

He adds: “I don’t think that the real bad stuff comes out of the podcasting and documentary crew; I think the real bad stuff comes of 4chan and then few Reddit subsets, forums and maybe Discord.”

Like so many before him, he describes the internet and current true crime phenomenon as the “wild, wild west.”

At Investigation Discovery, Jason Sarlanis, President of Crime and Investigative Content, Linear and Streaming tells The Independent the focus is on examining “the effects of crime on our culture, whether it’s the very personal perspective of the people touched by that specific crime to how we analyse crime through our different reporters, etc, to how we engage with law enforcement.”

He points to viewer engagement with shows such as In Pursuit with John Walsh, which has been airing on Investigation Discovery since 2019.

“Over the course of doing that show, we have engaged with our viewers to help catch 37 fugitives,” he tells The Independent. “Incredible - absolutely incredible. So that’s taking an entertainment programme and using it to mobilise the viewer in such a way that we’ve actually helped law enforcement. That’s really a powerful thing.”

He concedes, however, that “true crime popularity has made my job difficult, because now every network and platform, whether they are devoted to true crime or just dabble in true crime, is competitively going after the same stories as we do.

“So ultimately, that has really challenged us not necessarily to be the only game in town but to to be the best game in town.”

The competition is, undeniably, fierce - whether from streaming platforms, TikTok users or self-styled true crime influencers.

One thing will distinguish the bad actors from the meritorious content creators, though, says Ms Turney: Intent.

Many of the armchair detectives – extremely talented ones – have good intentions: Most people point to the prime example of Don’t F**k With Cats, which chronicled how kitten-loving internet sleuths tracked down a serial killer after becoming enraged by his videos of animal torture.

“As long as you have good intentions, it usually works out and you can minimize harm ,” Ms Turney tells The Independent. “I think when you go into it thinking, ‘This is a huge case, Oh my gosh, I’m gonna get so many views, I’m gonna get this exclusive interview with this family member, I’m going to ask them the tough questions’ ... I think that’s when it becomes a little bit murkier, because it goes back to intention.

“Are you there to get views and get downloads and make money? Or are you there to really help this case?”

There is a responsibility on viewers and content consumers, as well, to vet material and avoid further fanning the frenzy, as unrealistic as that may seem.

“I think the more that we expose how true crime is really made, the more we’ll see that shift in consumers,” Ms Turney says. “And once we see the shift in consumers, then we’ll see the shift in creators – because, unfortunately, they’re going to keep doing what works ... If it works, if it’s not broke, they’re not going to fix it.”

There is then a responsibility on consumers by default, she says, urging people, that, if they “hear something that feels wrong, turn it off … once they see that dip, they will pivot.”