Three-quarters of Australia’s freshwater fish species are found nowhere else on the planet. This makes us the sole custodians of remarkable creatures such as the ornate rainbowfish, the ancient Australian lungfish and the magnificently named longnose sooty grunter.

So how are these national treasures faring? To find out, we undertook the first comprehensive assessment of Australia’s freshwater fish species. We examined extinction risks and drivers of decline, before reviewing existing conservation measures.

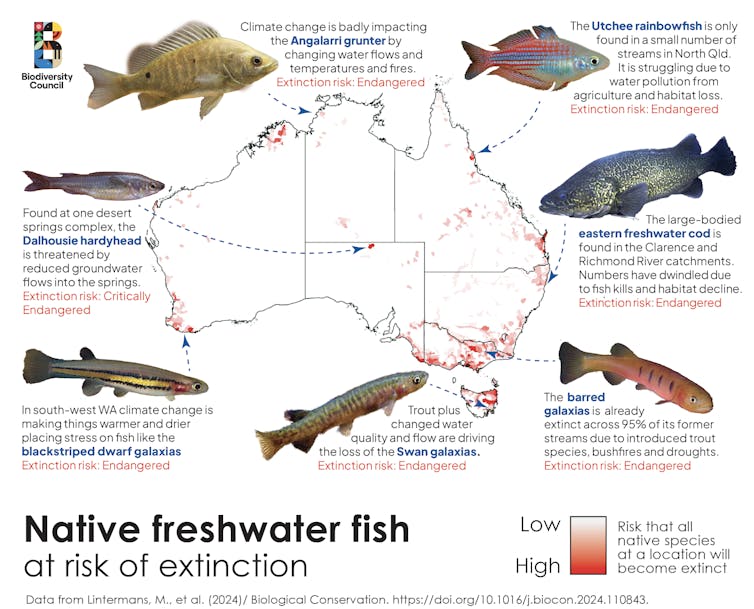

Our results paint an alarming picture. More than one-third (37%) of our freshwater fish species are at risk of extinction, including 35 species not even listed as threatened. Dozens of species could become extinct before children born today even finish high school.

The study also reveals Australia has been putting its eggs in the wrong basket for conservation by taking actions that don’t address immediate threats, such as pest species and changes in stream flows. Our research points to more effective solutions if governments are willing to step up their efforts.

Identifying species at risk

Recognising when species are in trouble is the first step in preventing their extinction.

Before this study, the extinction risk of most freshwater fish species had never been assessed. The group had never been looked at overall.

We evaluated the conservation risks of 241 species using globally recognised criteria (the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species).

We began our assessments by gathering a team of 52 Australian freshwater fish experts for a five-day workshop in 2019. These experts came from universities, research organisations, museums, state government agencies, natural resource management, consultancies and non-government groups.

Together, we used information from scientific publications, museum databases, Atlas of Living Australia records, government datasets, citizen science data, and our own knowledge of freshwater fish as it applied to the task.

We identified dozens of freshwater fish species that were in trouble, but had not been recognised as threatened. This brings the proportion of our freshwater fishes at risk of extinction to a third.

Some species have declined to the extent that they could disappear after a single disturbance, such as ash washed into streams after a bushfire or the arrival of an invasive non-native fish such as trout.

We also found one New South Wales species, the Kangaroo River perch, is now extinct.

Get them on the list

At present, 63 freshwater fish species are on Australia’s national list of species declared as threatened under federal environmental law.

We identified 35 more species that should be listed, based on the available evidence. They include:

- ornate rainbowfish and longnosed sooty grunter (vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, the global list of threatened species)

- salamanderfish (endangered on the IUCN Red List)

- the slender carp, Drysdale and Barrow cave gudgeons in Western Australia (critically endangered on the IUCN Red List).

Maintaining an accurate threatened species list is important. When species are in trouble but not listed, they miss out on basic protections and are unlikely to receive any conservation attention.

We also identified 17 already listed species that should be reassessed by the government as their risk categories need to be changed.

For example, the remarkable freshwater sawfish, found in northern Australian rivers, is listed as vulnerable but all evidence indicates it’s now critically endangered.

One sliver of good news is the fact that the Murray cod, a favoured sport fish across eastern Australia, is now doing better and could be assessed to be removed from Australia’s threatened species list.

Address the causes of decline

To prevent species extinctions, you need to address the causes of their declines. That might seem breathtakingly obvious, yet our review found a spectacular mismatch between the major threats to species at risk and the most common conservation actions.

The top three drivers of decline are invasive fish (which threaten 92% of threatened freshwater fish species), modified stream flows and ecosystems (82%), and climate change and extreme weather (54%).

For example, Australia has 40 galaxiid species, scaleless native fish shaped like slender sausages that grow to less than 15cm. But 31 of these are threatened with extinction – and rainbow and brown trout, two introduced predators, have been the biggest driver of their loss.

Australia’s southern states are greatly adding to the problem by releasing millions of trout into waterways each year for recreational fishers.

The endangered eastern freshwater cod has dwindled in part due to historic fish kills linked to dynamite blasting and pollution from mines and agriculture. It remains threatened by changes to river flows, removal of woody snags, and other damage to its habitat.

The endangered blackstriped dwarf galaxias is being stressed by the changing climate in southwest WA. Warmer and drier conditions are resulting in lower water levels and warmer water.

The other major threats facing native fish are agriculture and aquaculture (38%), pollution (38%), hunting and fishing (19%), energy production and mining (17%), and urban development (13%).

For example, the endangered Utchee rainbowfish is struggling due to habitat loss and water pollution from farms surrounding the small number of north Queensland streams where it lives.

In contrast, the most common conservation action was simply the fact that the species occurred in a protected area (88%) or conservation area (55%).

Sadly, invasive species and climate change don’t recognise or stop at protected area boundaries.

Prevention and control of invasive species has occurred for only 21% of affected threatened species, mostly in Tasmania.

A blueprint to end extinctions

Without a major funding commitment to address the actual drivers of native fish losses, species will continue to decline, and extinctions will soon follow.

The most important conservation actions for native freshwater fish are:

update the national threatened species list to include all at-risk species

tackle invasive species such as trout, gambusia and redfin perch

identify, establish and protect additional invasive-fish-free refuge sites for species that currently occur only in a small number of locations and could be wiped out by a single event such as a bushfire

halt ongoing habitat loss and improve habitats that have been damaged

improve freshwater flows to maintain habitats such as wetlands and streams, improve water quality and give fish the natural cues they need to breed.

In 2022, the Australian government made a commitment to end extinctions. Our study provides a blueprint for how to do that for our overlooked native freshwater fish.

Mark Lintermans was a member of the ACT Scientific Committee and the NSW Fisheries Scientific Committee, a previous convener of the Australian Society for Fish Biology Threatened Fishes Committee, and the Alien Fishes Committee. He now provides research, monitoring and advice for threatened freshwater fish management as director of a small consultancy company. He receives funding from New South Wales and national government departments for threatened fish projects.

Jaana Dielenberg was employed by the now-ended Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program, which led an earlier stage of this research. She is a Charles Darwin University Fellow and is employed by the University of Melbourne and the Biodiversity Council.

Nick Whiterod works for the Goyder Institute for Water Research, Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth Research Centre, which is funded by the national government to delivery research in the region. He is a member of the New South Wales Fisheries Scientific Committee.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.