As the Reserve Bank expresses concern about the scale and profitability of small finance businesses, firefighters will vote today on the very survival of their credit union

The introduction of a law setting in place $100,000 deposit guarantees can't come soon enough for members of the NZ Firefighters Credit Union, whose much-loved institution is on the brink of failure.

Firefighters will vote today on whether to transfer their business to the bigger NZCU Auckland or, if they can't agree on that, whether to call in the liquidators.

It comes as the Reserve Bank warns in its Financial Stability Report of the low returns on assets in the country's diminishing number of credit unions. Adrian Orr tells Newsroom: "Over recent times, they have been quite significantly challenged on scale and profitability."

Ever since the $380 million Government bail-out of BNZ in 1990, successive ministers have treated the big banks as "too big to fail". The Reserve Bank has required them to increase their capitalisation, with new rules coming into effect this year.

By contrast, there are concerns that the small credit unions, and some other building societies and finance companies, are too small to survive.

Last month, regulators advised that the Firefighters Credit Union was in breach of the trust deed for failure to comply with requirements under the Friendly Societies and Credit Unions Act 1982.

They agreed to hold off sending in the receivers until after Friday's meeting, as long as the credit union's capital ratio remains above 5 percent. It has ceased new lending, it's not accepting new members, and it is required to keep operating expenses to a minimum, and undergo daily supervision.

Chair Mark Virtue has issued a message to member on the credit union website. "As a small financial entity, we are finding it difficult to compete due to higher costs associated with delivery of financial services and, in recent years, increased costs of compliance," he says.

"We are not alone - the number of credit unions in New Zealand has reduced from 70 (20 years ago) to 30 (10 years ago) to just eight today."

“In terms of the additional strain credit unions will face because of the ever increasing regulatory change, I agree 100 percent that smaller financial institutions such as ours will suffer.” – Rudolf Laumatia, NZCU Auckland

Even the 5 percent is well below regulatory requirements, Virtue admits. Capital ratio is the level of capital in relation to the union's credit exposures and other risks.

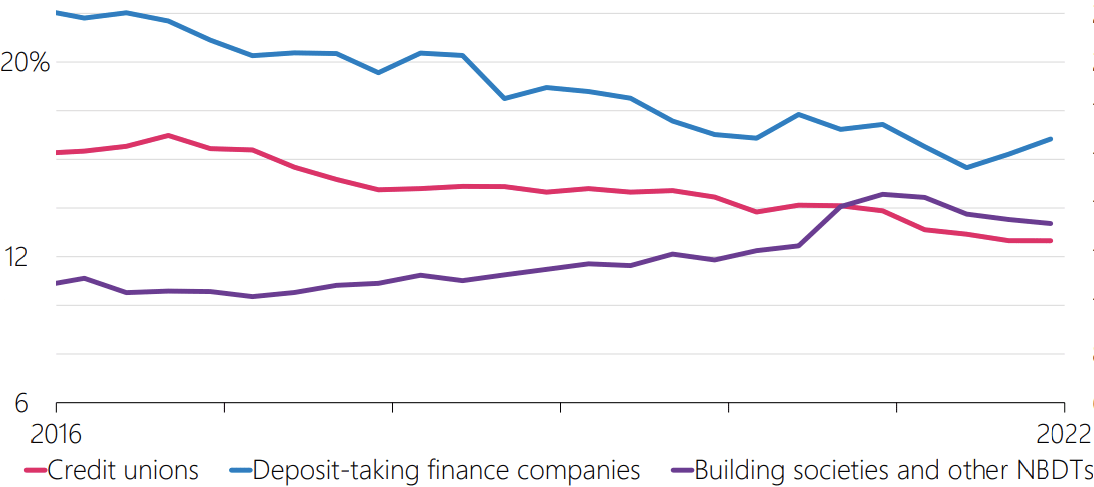

The Reserve Bank requires a minimum 10 percent capital ratio, which Firefighters can't meet, and some other credit unions are also struggling to stay above that figure.

The credit union was formed in 1976, at a meeting at the Central Fire Station in Wellington. Last year, its board attempted a merger with credit union Bayside but members voted down the plan. So the vote to merge with NZCU Auckland is the organisation's last chance.

But in the past few years it says its audit and compliance expenses have soared. Its audit fees, alone, increased by $156,000 in 2020, and 400 percent over the past three years. Virtue has told members they cut wages (down 21 percent), legal costs (down 50 percent) and accounting fees (down 33 percent) but it isn't enough.

Rudolf Laumatia, the new chief executive of NZCU Auckland, told Newsroom that unless the Reserve Bank and other regulators changed their approach to small financial institutions such as credit unions, "the future of non-bank deposit takers will be in doubt".

Capital ratios: Credit unions, finance companies, building societies

Even bigger credit unions such as NZCU Auckland were struggling. "In terms of the additional strain credit unions will face because of the ever increasing regulatory change, I agree 100 percent that smaller financial institutions such as ours will suffer," he said.

NZCU Auckland has total assets of $15.3m, and a capital ratio of 15.1 percent. Yet its non-performing loans ratio is still 3.40 percent. "Consolidation with other credit unions is a definite outcome should the regulatory controls continue to be a major factor."

Laumatia said the Reserve Bank had taken a "one-size-fits-all approach" to regulation.

“The compliance costs being rolled out blanket style without taking into consideration the member owned business model is prohibitive to their continued ability to operate and be competitive.” – Roz Henry, NZ Coop

"The issues that have plagued banks and financial institutions in regards to poor lending practice, for example, aren't necessarily issues found with us. Scale is a factor but we have a more member-based approach where the social factor of help is more prevalent in our decisions and is written within our policy.

"We as a collective are too small for the Reserve Bank to take a serious look at, unlike overseas where credit unions are an influence amongst financial institutions. In New Zealand we are not, so having our voice heard is difficult."

In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, and the collapse or bailout of finance firms such as Hanover and South Canterbury, governments have tightened controls on small lenders and deposit-takers.

Bank, credit union and deposit taker branches (per 100,000)

Since 2010, licensed non-bank deposit takers have been required to have a long-term, issuer credit rating and a minimum capital ratio of at least 8 percent - or if they don't have a credit rating, a capital ratio of at least 10 percent.

And Finance Minister Grant Robertson is expected to introduce a new Deposit Takers Bill to Parliament in the next month or two, creating a single regulatory regime for non-bank deposit takers and banks, on-site inspections, and setting in place deposit guarantees of up to $100,000 to protect parental investors in the event of a collapse.

The deposit insurance will be prioritised in order to have the scheme up and running in 2023.

“While non-bank deposit takers comprise a small share of the financial system, in some instances they provide banking services and loans to customers unable to access these facilities from banks.” – Reserve Bank Financial Stability Report

Robertson said last year that the $100,000 guarantee would be enough to fully protect 93 percent of depositors. “These measures mean individuals will have up to $100,000 of their deposits in any eligible institution guaranteed in the event of the failure of an institution."

The bigger credit unions are members of industry association Cooperative Business NZ. NZ Coop chief executive Roz Henry said the Council of Financial Regulators, which includes the Reserve Bank, was rolling out compliance costs blanket style without taking into consideration the member-owned business model. "It is prohibitive to their continued ability to operate and be competitive."

They were asking regulators to take a risk-based approach, along with review timings for rollout given the interruptions caused by the Covid pandemic. But regulators had been unresponsive.

"To date there has been limited engagement by this audience to work through how this might work," she told Newsroom. "This is disappointing given that if you look at what’s happened in Australia, the government have recognised the importance of the mutual and credit union sector and have ensured their continued ability to operate and remain competitive.

"Given that internationally there is a strong drive towards more collective business operations, it’s surprising particularly under a Labour government that this is not up for consideration."

In this week's Financial Stability Report, the Reserve Bank said there were 18 non-bank deposit takers operating in New Zealand. The stock of total lending was around $2.8b, compared with more than $500b in lending outstanding for banks. Most credit union and building society lending was for housing and consumer loans.

"While non-bank deposit takers comprise a small share of the financial system, in some instances they provide banking services and loans to customers unable to access these facilities from banks."

Newsroom asked about their risk exposure and capitalisation. Reserve Bank leadership expressed confidence about their capitalisation; less so about their returns. "We've worked with them continuously around ensuring that they are adequately capitalised and have adequate liquidity," Adrian Orr said. "Over recent times, they were quite significantly challenged on scale and profitability, but around capital liquidity it's the story as per the banks."

Last year, Newsroom reported a Reserve Bank watch list of 12 small financial institutions licensed to take cash deposits. One was Steelsands credit union, which had just taken over NZCU Employees Credit Union.

Chair Bhikhu Bhana reported that the credit union's financial bottom line had been severely impacted. "The board have had to make difficult decisions, to improve the income stream we have had to increase fees," he reports. "It was a decision not taken lightly, we do hope that members will understand that this current environment is unprecedented."

NZCU Baywide took over Aotearoa Credit Union, Credit Union South and Credit Union Central two years ago. That was followed by Steelsands taking over NZCU Employees last year.

The number of licensed finance companies is also shrinking. UDC Finance Ltd asked to have its licence cancelled last year.

And FE Investments went into liquidation holding about $55m of depositors' funds. Liquidator Rhys Cain says in his latest official report that he has identified potential claims against the company, and is inviting creditors to let him know if they'd be prepared to fund recovery action, including into the action of the conduct of the company's directors.

KPMG has published a report on credit unions and other non-bank financial institutions.

Bank and non-bank institutions alike have expressed concern about the “unnecessarily onerous” requirements of the new Credit Contracts Act, which requires them to look more closely at borrowers’ spending, the report says.

Lending institutions may have to reject up to 25 percent of loan applications, it says. There will be less risk appetite, especially from the banks, which may mean non-bank institutions and even unregulated high-street lenders pick up some of the riskier loans.

“Anecdotally, we heard that tier 2 lenders (and even tier 3 and 4) were benefiting from loans that tier 1 lenders would no longer write,” the report says.

KPMG says the non-bank institutions tend to be smaller, and so they don’t have specialised teams focused on the Credit Contract Act changes.

With banks refusing loans, this could have the unintended consequence of increasing the number of people who are “underbanked” or “unbanked”. “Without the opportunity of borrowing and demonstrating both a willingness and ability to repay, they become stuck in a cycle of borrowing from the unscrupulous as you need credit to get a credit history, which you need in order to get a loan from a responsible lender.

“There remained a non-bank sector view that some of those who need credit the most may be locked out by the very Act designed to protect them.”