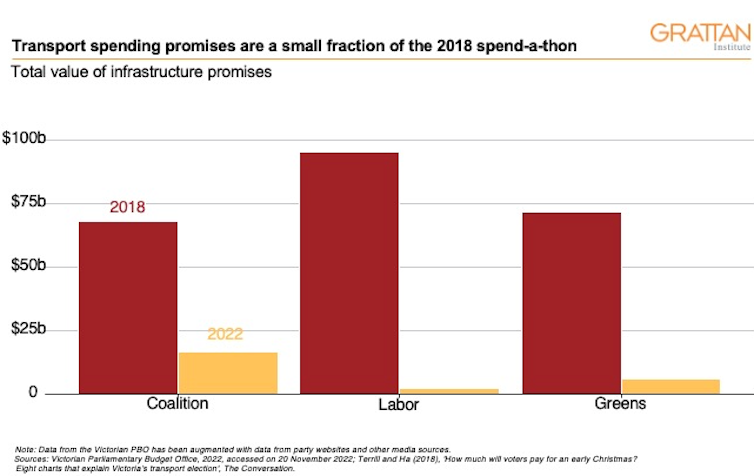

An election campaign can sometimes feel like Groundhog Day, but this Victorian election is genuinely different. While the major parties are still making plenty of transport promises, they’ve dialled them way down from the dizzy heights of 2018.

Our hope for the next election? Stop promising projects on the hoof, and start listening to what Infrastructure Victoria and Infrastructure Australia assess as worthwhile.

The biggest difference between the transport promises made this campaign compared to last time is scale. Back in 2018, the Coalition promised to spend $68 billion and Labor an eye-watering $95 billion, of which about half was for the Suburban Rail Loop. This time around, we calculate the Coalition’s promised new spending is just 25% of last time’s, at $16.7 billion, and Labor’s a tiny 2%, at $2.3 billion.

The most fundamental distinction between the two major parties, though, is not so much in what they are promising as in what they’re not promising. The Andrews government’s signature policy, the Suburban Rail Loop, is no longer just an election promise for Labor, but scrapping the loop is very much an opposition promise.

Back in 2018, we expected to pay $50 billion for a 90km tunnel looping from Cheltenham through Glen Waverley, Box Hill, the airport, and terminating at Werribee. We’ve since learned that the government thinks the eastern and northern sections will cost between $31 billion and $51 billion to build and run for 50 years. The Parliamentary Budget Office thinks it’ll cost $200 billion.

The opposition plans to scrap the loop and redirect the $34.5 billion committed so far to health care.

Read more: Budget restraint? When it comes to transport projects, it's hard to find

Pitching to different voters

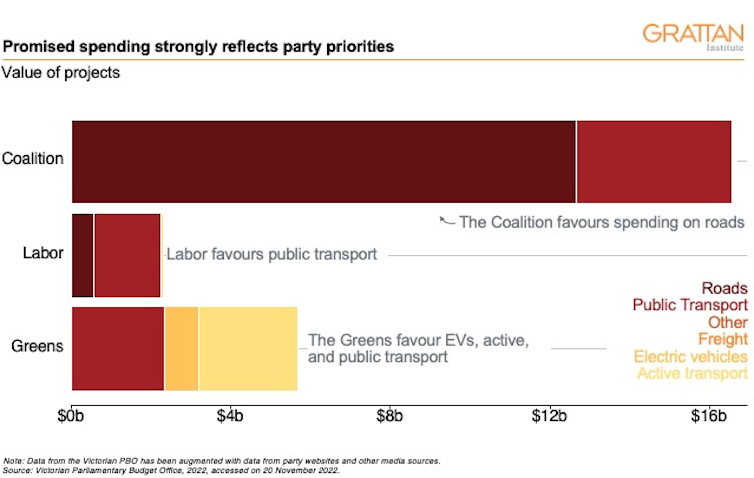

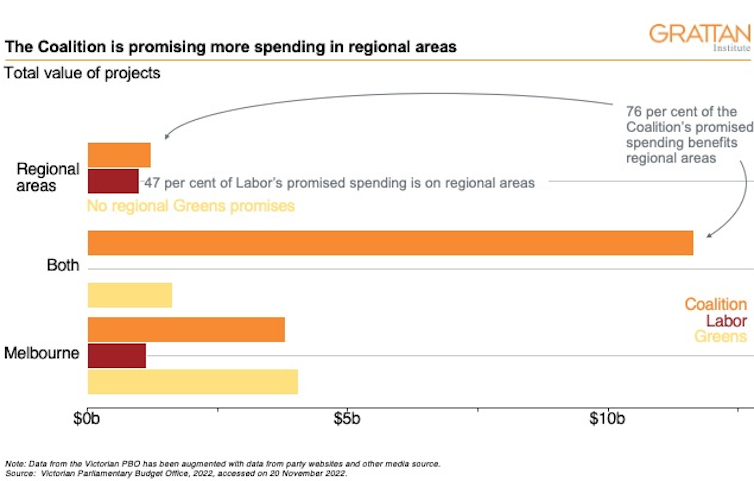

It’s perhaps less surprising that parties are playing to different heartlands. The Coalition favours roads, right across the state, while Labor favours public transport, with a focus on the city. These preferences show up repeatedly in elections, and they’re quite pronounced.

The Greens favour public, active and electrified transport, and are firmly focused on Melbourne.

The two major parties have promised 32 projects valued at $100 million or more, but they agree on just one: stage 2 of the Barwon Heads Road duplication. 2018 wasn’t much better, with the parties agreeing only on North East Link and Airport Rail Link.

New South Wales does things differently: in the 2019 NSW election campaign, Labor and the Coalition agreed on three of the four largest projects promised.

Independent advisory bodies ignored

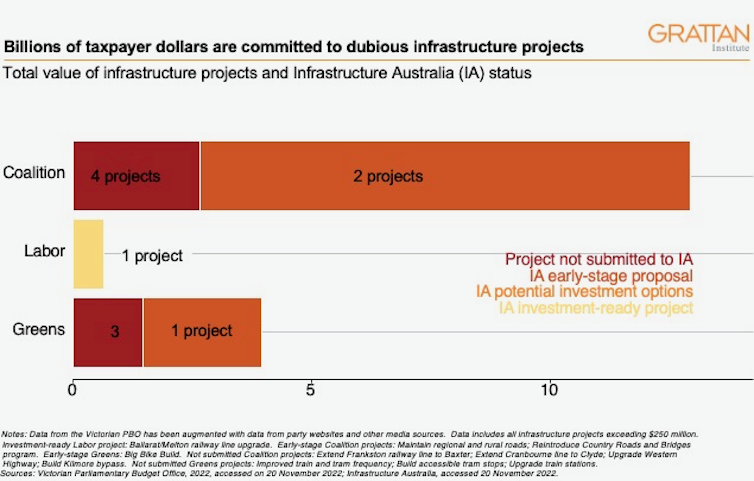

One reason the Victorian parties diverge so markedly on transport priorities is that they don’t pay much attention to the views of the independent advisory bodies, Infrastructure Victoria and Infrastructure Australia.

Infrastructure Victoria has produced a 30-year strategy for the state’s infrastructure, and it doesn’t mention some key policies of both parties. For instance, the Coalition has promised $2 tram and bus fares, and Labor has promised to cap regional public transport fares. But what Infrastructure Victoria recommends is a nuanced combination of off-peak discounts, reduced tram and bus fares, removal of the free tram zone, parking reform, and a congestion pricing trial in inner Melbourne.

Infrastructure Australia is supposed to scrutinise the business case of any infrastructure project where the proponent is seeking $250 million or more in federal funding. Up to 11 promised Victorian projects are in this category, but Infrastructure Australia has assessed only one as being investment-ready. The other ten are not even at the stage of evaluating potential investment options.

Read more: Of Australia's 32 biggest infrastructure projects, just eight had a public business case

The one project that is investment-ready is Labor’s proposal to upgrade the Melton line. Of the rest, three are what Infrastructure Australia calls early-stage proposals, and seven have not been submitted to it at all. The three that have reached early-stage status are the Coalition’s proposals to commit $10 billion to road maintenance and to reinstate the country roads and bridges program, and the Greens’ Big Bike Build.

A shift to many smaller projects

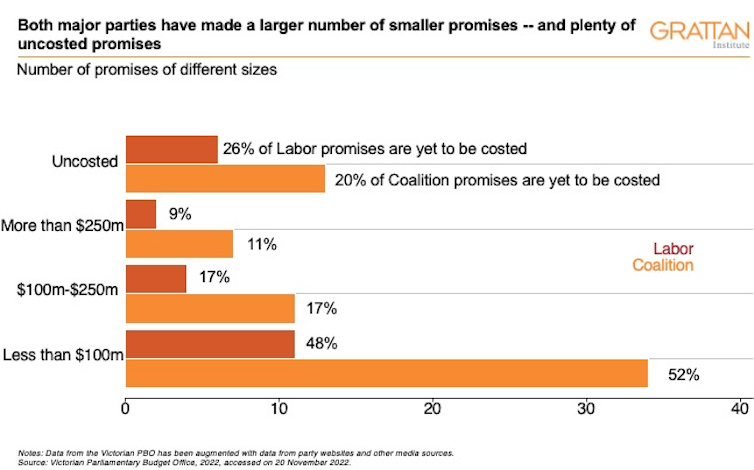

This election also stands out for the large number of smaller projects worth less than $100 million. That was also a feature of the federal election in May. About half of both the Coalition’s and Labor’s promised projects in Victoria are worth less than $100 million.

Interesting for its absence from Labor’s platforms is a focus on electric cars and bikes. The Coalition promises to pause the distance-based charge for electric vehicles until 2027, at a cost of $82 million, and spend $50 million establishing 600 new electric vehicle charging stations across the state. The Greens want to manufacture 3,000 electric buses, subsidise the purchase of electric cars, subsidise two-way chargers, fund more public chargers and ban petrol car sales from 2030; none of these policies have been costed. What’s the bet we’ll see a lot more action in this sphere in 2026?

In the end, this Victorian election campaign has turned out to be far less profligate than the last one. The promised spend is a small fraction of what it was in 2018 – but the quality of the promises is no better.

Voters should demand more. Whoever wins the election should commit to a transport program that focuses not so much on the political advantage to be had from dreaming up new projects as on rigorous business cases before – not after – the promise to invest.

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute’s board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and Grattan uses the income to pursue its activities. Marion Terrill does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any other company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Ingrid Burfurd does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any other company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.