What do we owe our departed loved ones? The people once behind the faces that stare at us — happily or blankly or beseechingly — from those black-and-white photographs?

I’ve been thinking about that lately, moving my parents here from Colorado, packing up box after box of albums jammed with fading Kodak photos of ordinary moments and once-in-a-lifetime vacations. Albums now in storage; albums no one might ever want to look at again.

I know I’m not alone here. But I was pleasantly surprised Saturday to see the big front page treatment the Sun-Times gave Friday’s unlocking of the 1950 U.S. Census Bureau data by the National Archives. I thought the joy of plunging into old records and tracking down relations was a personal quirk. Apparently not.

Opinion

Saturday morning I dove into the database, starting with my mother’s father, Irwin Bramson. Too easy. Go to the website, https://1950census.archives.gov/. Go to “Begin Search.” Plug in the state and city, in this case Cleveland Heights, Ohio. There was exactly one result. Zoom in on the photographed census form. There is his little household: wife Sarah, my mother June, then 13, her younger sisters, Carol and Diane. My grandfather’s nation of origin was Poland and his job, an accountant in a factory — Accurate Parts Manufacturing, maker of clutches. My grandmother was born in Russia. Nothing surprising there.

My father’s father I knew would be harder. A more common name in a far bigger pool. When I plugged “Sam Steinberg” into the census for the Bronx, New York, up popped 4,585 hits. The machine learning used to read scrawled cursive entries can be maddeningly imprecise. One of the hits was “Sam Silibority.”

I tried the “wade in and start looking” technique, but soon gave up. It doesn’t allow you to search by street names.

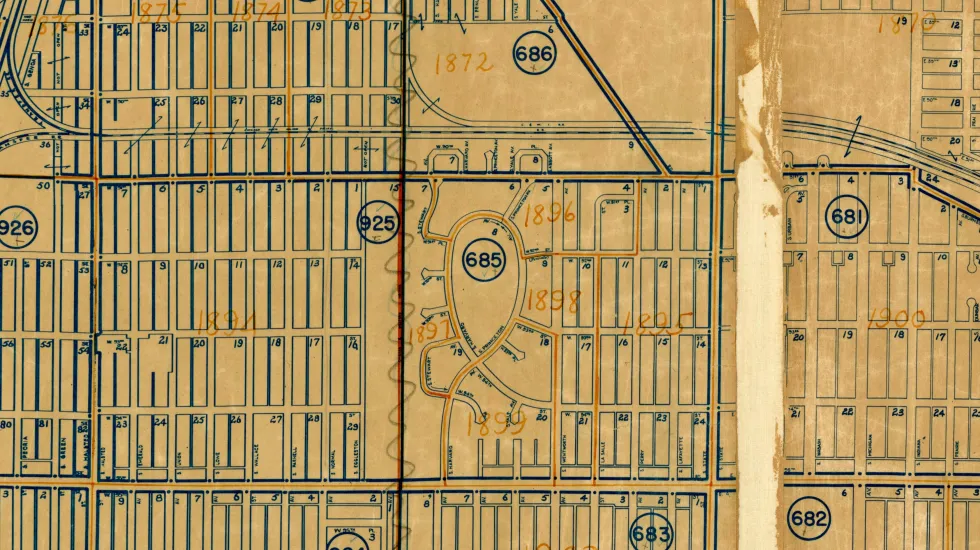

However, if you really want to find someone, there is a way, though it takes work. The census site links to the National Archives collection of Enumeration Maps, which divide every census region into block-by-block tracts. The maps can be difficult to read. I couldn’t even find Barnes Avenue on the 1950 map. But I used a trick I want to share: I went to Google Maps, plugged in my grandfather’s address, 2161 Barnes Avenue, figured out where that was in the greater Bronx, just south of Pelham Parkway, at the corner of Barnes and Lydig, and how to get there from a spot I could see on the ED map. There it was, Enumeration District 3-1157.

Nothing came up in the census records. Maybe the name didn’t register. I looked through dozens of pages. Nothing. I looked at the district description: “Bounded by Pelham Pkwy. South; Barnes Ave. to and excluding dwelling at house number 2161.” Ah. Helpful hint: check those descriptions first.

So I tried 3-1158. “No records found.” But it had to be there. So I went into the listings again, page by page, and practically following the census taker down the street, past the apartment buildings: 2194, 2184, 2164. Then 2148, 2146. They passed 2161. I kept going. Big smile at 2145. She had crossed Barnes Avenue.

I found it: my grandparents, both age 47, and my father, 17. The most interesting aspect was how my grandfather, given to pin-striped, double-breasted suits, large cigars and fancy Packard automobiles, described himself. Not as a “sign painter,” but a ”commercial artist.” Naturally.

As I did this digging, a question kept tugging at my sleeve: What is the point? I have all these letters I’ve never looked at, yet. The answer is simple: If you get lost someday, your data hidden among millions and millions of anonymous Americans, wouldn’t you want someone to come looking for you? I would.

Flush with success, I hunted for a trio of Chicago writers. Gwendolyn Brooks was nowhere to be found; turns out ”Gwendolyn” was a quite common name in 1950. I tried another writer. There he was, at 1523 Wabansia, with “Olsen” crossed out, and “Nelson” written in. Exactly the sort of minor indignity that would plague Nelson Algren, 41, who listed his job as “writer” in the business of “books.” You could almost hear him testily correcting the census taker. “It’s Nelson, not Olsen.”

Not many “Terkels” either. There he was, under Louis E., not “Studs,” with his wife Ida, on Wrightwood, not Castlewood, where they ended up. He listed himself as a writer of radio programs — he was, before being blacklisted — and I couldn’t help but notice he’s listed between a hospital waitress and a janitor, a hint at his future scope of interest that led to his classic book, “Working.”

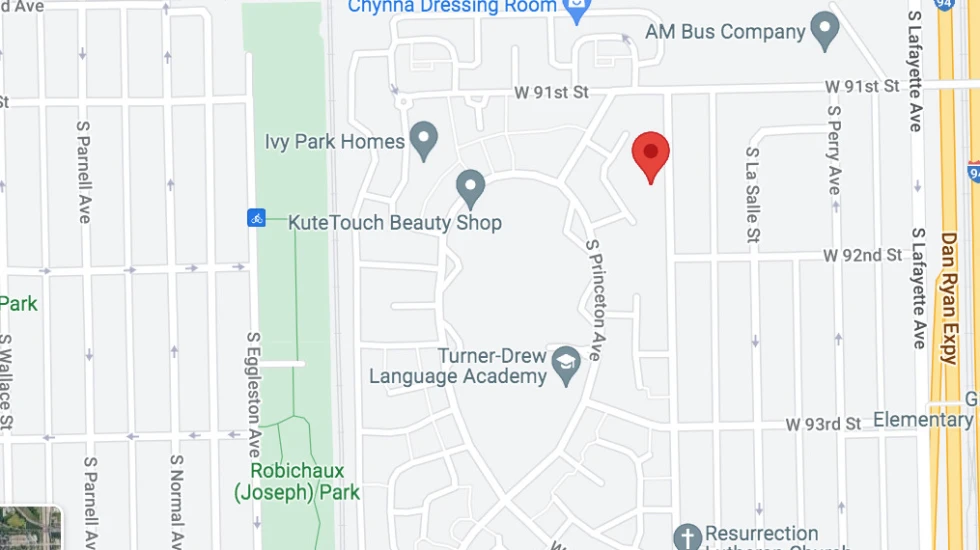

Back to Gwendolyn Brooks, for the Full Boy Scout Try. Chicago’s Enumeration Map has almost no street names. But her address is one of the better known in literature: 9134 Wentworth. Google Maps showed it just east of a very distinctive ellipse formed by Princeton Park. I found it in Enumeration District 103-1896, and started to search.

At first I thought I’d be disappointed. In the census form, “No one at home,” is written next to 9134 Wentworth. Census takers could be less than diligent when counting Black people, a tendency the Trump administration encouraged in the 2020 census.

But then a written note: “See P. 80.” I saw page 80.

There she is. No last name of her own, but under “Blakely, Henry,” her husband, no mean poet himself, listed as manager of an auto repair shop. Brooks’ birthplace is Kansas and the space for her job or business is left blank. Gwendolyn Brooks had no official occupation in the eyes of the government. I looked at the top of the form: May 13, 1950. Two weeks earlier, she had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry.