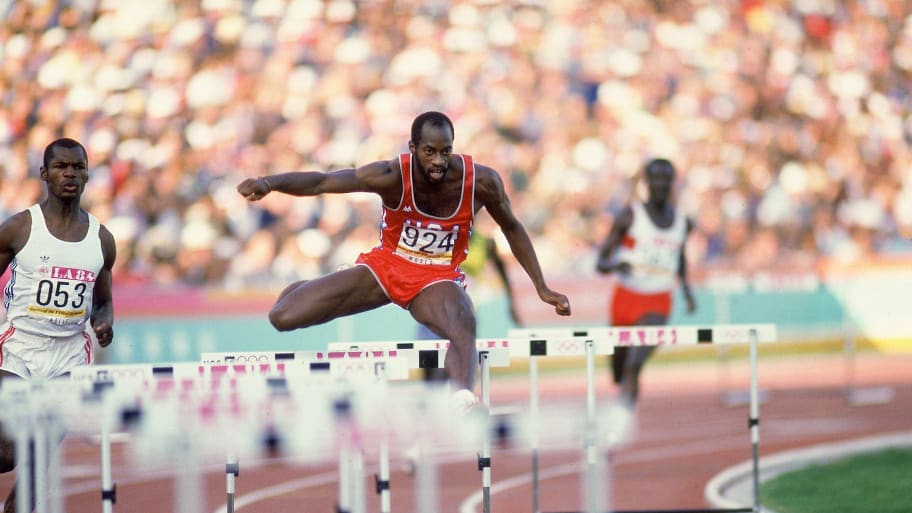

He had a singular knack for thundering down the track, covering 400 meters in fewer than 50 seconds … and, oh yes, clearing 10 three-foot hurdles along the way. He was the Usain Bolt of his day, an international track sensation, the GOAT in his event, a bankable TV star, whose shifts were shorter than the commercial breaks that followed his performances.

But now, in the second phase of his life, Edwin Moses has turned conversation into an endurance event.

He’s 68, Moses is. (I know, right?) Handsome, blessedly free of wrinkles, searching eyes behind stylish glasses, within a few “COVID pounds” (his term) of his competing weight. He’s all passion and energy; the answer to a simple question such as What’s a typical day like? wends its way from Berlin to Ghana, namechecking George Steinbrenner (we’ll explain later) and containing a word cloud that encompasses metabolic ratios, artificial intelligence, authoritarianism and free-form jazz.

Moses lives in Atlanta. He maintains, as ever, that “it’s cool to be a nerd.” Even though he is more than 36 years removed from the domination of competition, you wouldn’t know it, given his insight into the current state of play in track and field, and international sports in general.

Here, too, is a man who doesn’t suffer fools. He speaks without apology and doesn’t so much ruffle feathers as he leaves behind the desiccated carcass of the bird. One consequence: He is not exactly on the inside track of the global sports community. “Commissions, committees, panels, I’ve been kicked off everything,” he says. “But I’d rather be kicked off than be silent and let the wrong thing happen—or something I didn’t believe in.”

Forty years after the L.A. Olympics—one of the three Games Moses left bearing a medal—he is considering venturing to the Paris Olympics, but he’s still unsure what precise form this would take. His relationship with the International Olympic Committee is frosty. There are few corporate speaking or hospitality tent gigs in the offing. “Maybe,” he says, “I’ll try to get some sort of credential.”

A pity, this. Yes, because anyone with Moses’s body of work ought to be featured prominently in any Olympics. But more so, because as the figure who has done as much as anyone in sports to confront and reduce doping over the last 35 years, he deserves a better seat from which to watch clean competition.

Technically, Edwin Moses ran the 400-meter hurdles. But in truth, he hacked the 400-meter hurdles. He had all the requisite qualities for success: a perfect 6' 2", 180-pound physique; a bottomless work ethic; athleticism, agility, certitude and the required capacity for singular focus. But more critically, he reveled in solving the mystery of the event, using math and physics and biomechanics to find efficiencies to exploit and inefficiencies to avoid.

Moses discovered, within millimeters, how close to the lane marker he ought to run. He also found the ideal height for clearing the hurdle, sufficiently high that he wouldn’t clip the bar, sufficiently low that he wouldn’t waste even a millisecond suspended in air for too long. He figured out the optimal shoes and spikes for the track surface. He fixated on sleep and monitored his vegetarian diet. Decades before it was voguish, he recovered using ice baths, worked out wearing heart monitors and used computer readouts to analyze biometric data. “Man, they thought I was crazy,” he says now. “Was I ahead of my time or what? But the physiology part, the biology, the biochemistry, the need for good fuel. It matters! Can’t put diesel in a Ferrari. That’s always been my philosophy.”

Growing up in Dayton, Ohio, Moses was a self-described “super nerd” who would read the encyclopedia for fun. He recalls asking teachers if he could leave school a few minutes early. He would hastily pack up his books and his art supplies before the bullies could seek him out.

That Moses sought a head start says plenty about the muted role sports played in his adolescence. He could dunk at 5' 8" and run fast, and he played some high school football. But by his senior year he was highly recruited, not for track but for academics. He decided to attend Morehouse College, an HBCU in Atlanta, double majoring in physics and industrial engineering. At first—thinking of it more as a fun after-class activity than a future career path—he ran track, though the school didn’t actually have one. A track, that is. Instead, the team trained at nearby high school facilities.

These conditions forced Moses to think about his sport as both art and science. He contemplated angles and dynamics. Using his calculus skills, he concluded that leading with his nondominant leg first meant he’d effectively run as much as 20 feet less in each race. He also calculated that he needed to run an odd number of steps, so he’d take a consistent, precise 13 steps—later the title of his 2024 documentary—between each of the hurdles.

By 1976 he had qualified for the Montreal Olympics, his first international meet. No one—teammates, competitors, the media—quite knew what to make of this bespectacled 20-year-old, who was usually reserved, but would open up and speak at length about wind resistance and the electromagnetic wave theory course he’d start in a few weeks when he got back to school. And there was his extraordinary hurdling. In the final heat, he won gold, turning in a world-record time of 47.63.

If Moses awed crowds, he was awed by something else. “I saw the women from Eastern bloc countries, and they looked like they could have been on a football team. I mean they were cut, muscles bulging everywhere,” he says. “I think I’m gonna break the world record and my physique is nothing compared to these girls. Nothing. I was devastated for the American women. We had some of the best sprinters, best hurdlers, best everything. But when it came down to the Olympics, they just didn’t have the substances in their bodies.”

Nearly a year after his Olympic gold—and still a year from his Morehouse graduation—Moses lost a race in what was then West Berlin to West German sprinter Harald Schmid. What qualified as a mild upset at the time soon became an immortal date. Moses would not lose another race for nearly 10 years.

While his competitors engaged in mere running and jumping, Moses, unfurling his 9' 9" stride, would glide and soar. It’s hard to quantify Moses’s level of dominance. But consider: At one point he held 18 of the 20 fastest-ever times in his event. At another, there were 34 instances of hurdlers breaking the 48-second mark. Moses accounted for 30 of those.

After Moses was beaten by Schmid, each of his next 122 races became its own kind of set piece, the suspense embedded not in the outcome, but in how Moses’s superiority would reveal itself. The other guys on the track were more artistic partners than competitors. (Even Schmid, who won two Olympic bronze medals, conceded at one point, “I’ll never beat this guy.”)

Speaking to Esquire in June 1988, Dick Hill, a former coach of Moses, said, “You want the Olympic attitude, what it should be but seldom is? It’s Edwin Moses. Body and motion is my discipline. He’s the most remarkable athlete of the twentieth century. Perfection.”

Moses would have been a star (the star?) of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. The U.S., of course, boycotted those Games. Though it deprived him of the biggest stage in what was, notionally, the prime of his career, Moses was supportive of America’s decision. And he figured that, given rampant doping in the Soviet bloc, the U.S. would likely have fared poorly.

“Between ’80 and ’84 [doping] blew up,” he says. “Everyone knew who was doing it, who was likely doing it. Everyone knew the coaches, the trainers. And at that time, a lot of them were quite open about it. They used to talk about it on the buses in Europe all the time. What are you taking? It was an open secret. And I thought it was just devastating to the sport.”

“Was I ahead of my time or what? But the physiology part, the biology, the biochemistry, the need for good fuel. It matters! Can’t put diesel in a Ferrari. That’s always been my philosophy.” Edwin Moses

At the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, Moses took gold, winning in 47.75 seconds. Of course he did. He joined Paavo Nurmi, the “Flying Finn” from the 1920s, as the only Olympic runners to win an individual gold medal in the same event eight years apart. But the winner was something other than ecstatic. “I ran a better race in Montreal,”’ he said afterward. ‘’But I guess I have to look at my accomplishments in a different perspective now. Everybody talks about the streak, but I go into each race with a 0–0 record. I just try to cleanse my mind of everything else and not put pressure on myself by thinking about the streak or anything else.”

The streak was, equally, a blessing and a curse. It was a source of constant motivation, a source of personal challenge. He notes that it helped to get up for a race, when the stakes were not just winning, but also a prolonging of history. It was also a burden. Just as Roger Maris’s hair fell out as he was chasing Babe Ruth’s home run record and Joe DiMaggio later reflected on the absence of happiness during his 1941 hitting streak, Moses felt the stress acutely.

A July 1984 Sports Illustrated feature on Moses was titled “The Man Who Never Loses.” He comes across as a man hell-bent on talking about anything—art, science, politics—other than his streak. And, at the same time, hell-bent on keeping the streak alive.

Finally, inevitably, it happened. On June 4, 1987—nine years, nine months and two days in—Moses had his streak snapped. On a balmy day in Madrid, he lost his balance a bit on the 10th hurdle, throwing his timing off just enough for fellow American Danny Harris, who had won silver in ’84, to beat him, running 47.56 to Moses’s time of 47.69. That is, it took Moses stumbling—literally—for another world-class runner to defeat him. By just .13 seconds. And, even in defeat, Moses ran yet another race under 48 seconds. Equally disappointed and relieved, he was as philosophical as ever. “I ran a good race,” he said, “and the guy that beat me is 10 years younger and ran the race of his life.”

Throughout his decade of dominance, Moses was hardly inaccessible. He practiced openly on tracks in Southern California, where he drove a Mercedes adorned with the license plate olympyn. Having graduated from Morehouse with a B.S. in physics, he moonlighted as an aerospace engineer with General Dynamics, working on missiles and submarines, a real-life rocket scientist. And he … wait, what? ... yes, that previous sentence is true. Imagine, say, Tom Brady working a 40-hour-week desk job trading equities at Morgan Stanley during the NFL offseason. Moses didn’t do it because he needed the money. “I needed the stimulation. They were looking for Black engineers and I thought, Why not?”

He trained three times a day. He read. He wrote. Still, he never quite captured the public imagination as he should have. Maybe it’s because he won too much. Maybe he had too many facets that the tastemakers never quite knew how to position him. Mark Kram, sportswriting titan, once put it this way: “You don’t see him on TV exchanging banalities with Johnny Carson; in fact, you never see him anywhere except when he folds himself into the starting blocks and goes to work.”

For Moses, there were bigger issues to address than talk shows and photo shoots. One was athlete empowerment. How was it that track meets were held in massive stadiums, in front of 50,000 fans, and athletes were only making a few thousand dollars? “There was extra money the promoters paid [under the table] but that wasn’t honest either … The first time that I went to Europe, they tried to force me out of track meets because I was asking for too much money.” Soon Moses demanded—successfully—that track and field athletes receive contracts and not rely on off-the-books payments.

In 1981, IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch handpicked Moses to head the organization’s first Athletes’ Commission. “I was the one with the biggest mouth,” Moses jokes. Among his achievements: He helped design the Athletes Trust Fund, a program whereby amateur competitors could retain their status but still be remunerated. Moses presented the model to Samaranch, who ratified the plan. Thanks largely to Moses, the definition of amateurism was relaxed, and athletes could get paid and endorse products while still remaining Olympic-eligible.

He was also preoccupied with fighting doping. With a background in biology and chemistry—someone who uses terms like titration limits in casual conversation—he knew which muscles and times were attained honestly and which weren’t.

As someone who incorporated physics and calculus into his training in order to find incremental advantages, Moses found something particularly offensive about competitors who took shortcuts. He also worried for the cheaters. “Ethically, you’re stealing,” he says. “But I also knew enough about biology and chemistry to not mess around [with drugs]. I was scared for these guys.”

Much the same way he became an expert hurdler—gradually, then suddenly—he became an expert in anti-doping. He volunteered for committees and demanded tougher testing. He says the situation worsened in the ’80s, when—thanks in no small part to his efforts—big money finally flooded the sport and the incentive structure changed.

On top of that, dopers outpaced the detectors. Out-of-competition testing was essentially nonexistent. There were virtually no unannounced tests. And athletes were brazenly discovering new frontiers, such as testosterone, growth hormones and EPO. “I used to think 80% of the people were clean like me and 20% were on the dark side. By the time I finished, it was flipped,” Moses says.

At the 1988 Seoul Olympics, in the last race of his career at age 33, Moses took bronze. Those games might be best known, however, for Ben Johnson’s tainted 100-meter race, on the same track a day earlier. Moses had had enough. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) had yet to be formed, but Moses effectively set up a precursor. He rounded up 10 other conscientious American athletes and they demanded funding for out-of-competition drug testing.

They drew up the protocols, got them approved, raised the funding and Moses became chief of U.S. testing. “Hey, track and field was headed to a dark place,” he says. “Someone had to do something. I was like, If no one is stepping up, I guess I will.”

The 400-meter hurdles requires a precise path. But the life of the greatest-ever 400-meter hurdler is defined by detours. We’ll take one, too. Because cleaning up an entire sport wasn’t enough to fill his days, Moses took another full-time job in retirement. Reaching the unhappy realization that he could not become a doctor, having “run out the clock on med school,” Moses put to use his facility with numbers. Living in Atlanta and working toward an MBA, he worked for Robinson Humphrey, then a prominent financial services firm.

While serving on various USOC commissions, Moses had become friendly with George Steinbrenner. Demanding, impatient and stingy as he was as owner of the Yankees, Steinbrenner had long been well-regarded within Olympic circles, volunteering, contributing millions and steering committees. Steinbrenner turned to Moses for help investing in USOC funds.

Then, Steinbrenner engaged Moses to help invest and raise funds for the Yankees. Yes, by the mid-’90s, Edwin Moses had become George Steinbrenner’s banker of choice. When the Yankees played in the 1996 World Series, Moses sat in the Boss’s personal box. The assumption was that this was a jock-sniffing owner, keeping the company of someone ESPN would soon declare one of the top 50 athletes of the 20th century. Who knew this was a tycoon inviting his banker?

Ultimately, Moses’s career in finance was short-lived. The money was good. But he had a higher calling: making sure sports remained a force of good. In 2000, he was elected (unanimously) to become the first chairman of the Laureus World Sports Academy, a division of the international group that annually honors sporting excellence. That May, Moses stood on the stage when Nelson Mandela gave his famous speech. (“Sport has the power to change the world, it has the power to unite people in a way little else does.”) And Moses remained on the Laureus board for the next 20 years.

He took his job seriously, but Moses’s main occupation—and preoccupation—became his campaign against doping in sports. He visited labs. He interviewed athletes. He drafted white papers. When WADA was inaugurated in 1999 to promote, conduct scientific research and monitor the fight against drugs in sports, Moses was a founding member, and he eventually chaired the education committee. Simultaneously, he was a pillar of the U.S. anti-doping-agency (USADA) and was elected chairman in 2012.

In the ’90s, Moses made a fact-finding trip to Russia. He was something other than surprised when, he says, a dissident lab director explained the state of play. “He basically said, ‘We. Dope. Our. Athletes. All. The. Time.’ They showed us the books of the athletes, what they were taking, the doctors, the dosages, everything.”

Moses recounts the source explaining, “What we want to be able to do is test them so that they don’t leave the country. We want them to test positive in Russia.” Moses asked: What happens then? What happens to the Russians athletes who test positive? The source said flatly: “Oh, nothing. We just pull them off the team and we hope we don’t make a mistake next time.”

Before the 2014 Sochi Olympics, Moses was skeptical that much had changed. He was on record predicting that Russia was not beyond perpetuating a systematic, state-sponsored doping program for its athletes. When that scenario played out, Moses was both livid and energized.

He demanded investigations. He called out the conflicts of interests. He lobbied for harsh penalties. Concerned that WADA was shirking its duties, Moses and longtime USADA CEO Travis Tygart wrote a blistering letter to WADA president Craig Reedie demanding a full investigation of Russia’s practices. A sample passage: “For WADA to sit on the sidelines in the face of such allegations flies in the face of WADA’s mandate from sport, government and clean athletes and the role for which it was created.”

WADA finally acted, albeit belatedly, and recommended banning Russia from international competitions for four years. The Moses-Tygart letter sits on display at the Olympic Museum in Colorado Springs.

Tygart worked closely with Moses for more than a decade, including the successful USADA pursuit of Lance Armstrong. “What’s so unique about Edwin is that obviously he has the perspective of an athlete—[among] the greatest ever, certainly the greatest ever in his event,” Tygart says. “But then he also has a full appreciation of the science. A true Renaissance man.”

Declare a sport clean—or even cleaner—and you do so at your peril. Accurate, valid empirical evidence is hard to come by. A low rate of positive tests might suggest an absence of doping. It might also suggest inadequate testing or testing easily circumvented by short-lifespan drugs that avoid detection. (Armstrong, of course, repeatedly—and, sadly, accurately—maintained, “I’ve been tested 500 times and I’ve never failed a drug test.”)

Both data and anecdotes suggest that international athletes are less prone to doping than they were even a decade ago, certainly less than in Moses’s era. Even with heightened testing, both in sophistication and frequency, fewer athletes are testing positive. National federations that once resisted testing are now more rigorous. Records are no longer falling at suspicious clips. (“No Ben Johnsons,” says Moses.)

Inasmuch as doping is on the decline, some of this, Moses is quick to note, is owed to technology and advances in detection: “When we first started, they said, ‘You can pour a gallon of a steroid in a pool and we can detect it.’ Then it became a tablespoon. Now, it’s one drop. We can detect one drop in an Olympic-sized pool!”

Some of the decline is attributable to toughening protocol. Athletes are tested more often—and, critically, more unexpectedly—than ever. Athletes can be sanctioned for misstating their whereabouts and missing tests, like 2019 100-meter world champion Christian Coleman, who was given a reduced 18-month suspension for missing three drug tests in a 12-month span. They can be sanctioned for so-called “non-analytical positives,” that is, circumstances or other bits of evidence that suggest doping, even if there is not a positive sample. A name on a mailing list or syringes found in luggage, for instance, might be enough to trigger a violation.

It’s also impossible to talk about any decline in doping without crediting Moses. “I had nothing to gain,” he says. “I was winning anyway. But I feel like if I had been silent, I would be doing track and field a disservice. It was going to a dark place. Did I make a difference? I’d sure like to think so.”

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Track Icon Edwin Moses Is Taking on a New Challenge: Keeping His Sport Clean.