In June 2023, countries across the world celebrated Pride Month, set apart each year as a celebration of alternative sexual and gender identity. It is an occasion for members of the LGBTQ community to mark progress made on legal and social fronts on their rights.

The same month, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni signed into law the Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2023, which criminalises same-sex conduct, including a potential death penalty for those convicted of “aggravated homosexuality.”

This duality is in keeping with the varying nature of protection for LGBTQ rights around the world. This is why, as LGBTQ organisations highlight, Pride is still a protest today, as it was at the outset.

Why is June Pride Month?

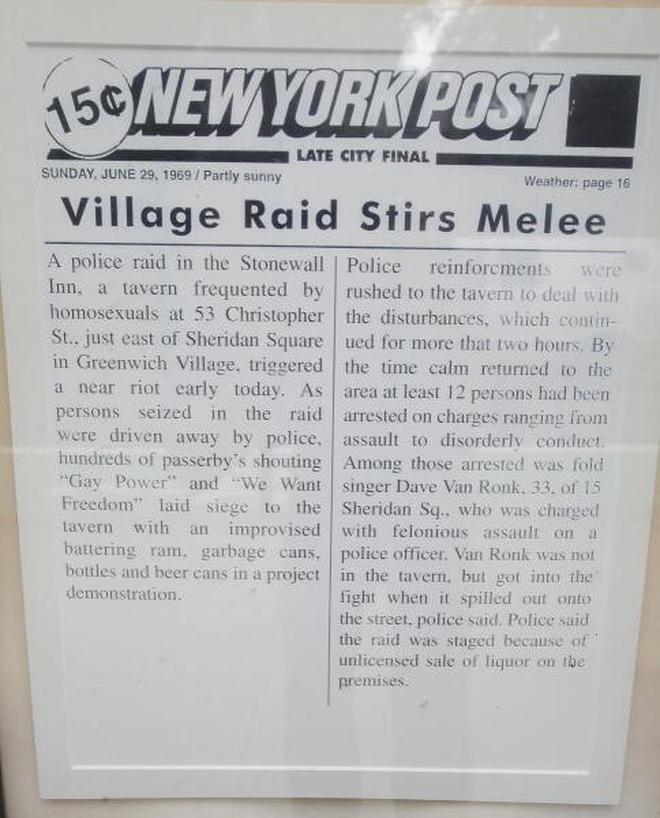

The short answer: the Stonewall Riots. To understand the significance of the Stonewall Riots, one must consider the socio-political climate of North America in the 1960s. Besides apartheid and racial inequality, most cities in America also saw discrimination of another sort; homosexual activity was illegal in all major American cities. This included cities like New York and Philadelphia.

This did not prevent gatherings and socializing at underground gay bars across the country. One of these was the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, New York City— an epicentre for gay gatherings in the city. The Stonewall Inn was reportedly operating without a liquor licence.

These bars were subject to frequent police interference and raids. In the early hours of June 28, 1969, nine policemen entered the Stonewall Inn for one such raid, arresting employees for selling alcohol sans licence and emptying the place of its colourful patrons. At the time, New York had a criminal statute in place which authorised the arrest of anyone not wearing at least “three articles of gender-appropriate clothing.” Many Stonewall patrons were in contravention of this and were taken into custody by the police.

This raid marked the third time Greenwich Village had been raided in a short space of time. This time, instead of dispersing, the angry mob stayed on. They began insulting the police and throwing bottles and small objects at them.

The police barricaded themselves inside the bar. Around 400 people continued to riot near the Stonewall Inn, eventually setting the bar on fire. Police reinforcements managed to quell the fire and the crowd, but the riots persisted for five days.

Although there had been earlier protests against the discrimination and harassment faced by the LGBTQ community, the Stonewall riots marked a turning point where lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people formed a united front against police action and bias.

This wasn’t the first initiative undertaken by LGBTQ persons to fight for their rights.

The history of gay rights in the U.S goes back to 1924, when the Society of Human Rights was founded by Henry Gerber in Chicago. Other organisations such as the Mattachine Society (founded in 1950), Janus Society (founded in 1962) and Daughters of Bilitis (founded 1955) also supported the cause, seeking political and social recognition of the rights of homosexual people.

Anti-homosexual policies in the military, as well as Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare, gave rise to pro-LGBTQ groups during World War 2 and the period that followed. The Red Scare was paralleled by the Lavender Scare, a fear campaign against homosexual people in the US. In 1953, President Dwight D Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450, under which gay men and lesbian women in the federal government were investigated and fired; thousands of government employees lost their jobs.

Among these was astronomer Frank Kameny, fired from his job with the Army Map Service in 1957. He sued the government, to no avail, and dedicated his efforts towards fighting for gay rights. Known by many as the “Father of the Gay Rights Movement,” Frank Kameny founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., picketed the White House, contested the American Psychiatric Association’s categorization of homosexuality as a mental defect, and coined the term “Gay is good.”

The Stonewall riots fired up the cause of LGBTQ activism further. A young activist called for nationwide protests each June honouring the Stonewall riots during the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations in 1969. It was thus that, a year after the riots, New York’s first pride march was held in June of 1970, on what was then called Christopher Street Liberation Day. Thousands marched in the parade, starting off in Christopher Street and ending in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow.

The following years saw similar pride marches in cities across the country. The slogan “gay power” was proposed for the march, but the theme “gay pride” was eventually chosen; the idea was that while the movement had yet not received political empowerment, its members felt pride in their sexual identity.

It wasn’t till 2003 that homosexuality was finally decriminalised in the U.S. And it was only in 2015 that the U.S. Supreme Court recognised same-sex marriage, in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Pride celebrations in other parts of the world

In the UK, the first LGBTQ Pride event was held on July 1, 1972, from Hyde Park to Trafalgar Square, London, attended by around 500 people. Around the 1980s, Pride events in the UK focused on the AIDS crisis which ravaged the gay community and also protested Section 28, under which the Conservative government of the day banned the “promotion of homosexual lifestyles” in schools.

Pride Month is not the only one set aside for celebrating members of the LGBTQ community. LGBT History Month is celebrated in the month of October, while National Coming Out Day is celebrated on October 11. This is as the first and second marches on Washington in support of those suffering from the HIV-AIDS and LGBTQ rights in 1979 and 1987 also took place in October. In the UK, February is earmarked as LGBT History Month, significant as the month Section 28 was abolished in 2003.

Pride parades too span the months of June, July and even August. The UK, as mentioned above, holds a Pride Parade on July 1. In Canada, different cities may hold pride parades on different days; both Montreal and Vancouver have Pride events scheduled for August 5 and 6 this year. Berlin and certain other nations in the European Union celebrate a Pride-equivalent day on July 23, called Christopher Street Day.

Pride History in India

India’s first-ever protests demanding rights for gay individuals happened on August 11, 1992. It was held by the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (ABVA) outside ITO Police headquarters in Delhi to protest the arrest of men from Central Park in Connaught Place on the suspicion of homosexuality.

Earlier, in 1991, ABVA published a pamphlet called Less than Gay— a citizen report on the harassment faced by members of the LGBTQ community in India.

In 1994, a medical team sought to look into the high prevalence of same-sex relations reported from Tihar jail. While ABVA activists wished to distribute condoms to inmates, then Inspector General of Prisons Kiran Bedi refused to grant them permission. The prison resorted to mandatory HIV testing and segregating those found positive for the virus.

That same year, ABVA filed a PIL in the Delhi High Court challenging the constitutional validity of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, widely considered one of the first legal protests against government repression of LGBTQ rights in India. It was dismissed in 2001. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a Victorian relic, criminalised sex “against the order of nature.”

By 2002, India’s HIV-affected population was placed by the government at around 3.97 million — second only to South Africa. While the country’s homosexual community was ravaged by the epidemic, police continued to harass members if they came forward for treatment. At the time, former Union Health secretary Sujatha Rao was instrumental in convincing the health ministry to take a pro-LGBTQ position; while Home Minister Shivraj Patil was bitterly opposed, while Health Minister Anbumani Ramadoss was in support. Lawyers also decided to argue for the rights of the LGBTQ community as a public health measure in order to succeed.

India’s gay community repeatedly mounted legal challenges post its failure in 1994. In 2009, the Delhi High Court held in Naz Foundation vs Govt. of NCT Delhi that treating gay sex between consenting adults as a crime was a gross violation of the fundamental right to privacy enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

However, in 2013, the Supreme Court overturned the Delhi High Court’s ruling in Suresh Kumar Koushal vs Naz Foundation.

In 2015, MP Shashi Tharoor introduced a private member’s bill in the Lok Sabha seeking to decriminalize homosexuality by amending Section 377 of the IPC. But it failed to pass in the Lok Sabha. Again, in March 2016, the Lok Sabha voted against the introduction of Mr. Tharoor’s Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Bill 2016 to amend Section 377— the second time in three months.

In 2017, the Supreme Court, in a seminal judgement, ruled that privacy was a fundamental right for individuals under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution, in Justice K. S. Puttaswamy vs. Union of India.

This set a judicial precedent that helped the legal battles of the LGBTQ community. On September 6, 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that Section 377 was unconstitutional “in so far as it criminalises consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex”, thus legalising “consensual same-sex acts between homosexuals, heterosexuals, lesbians and other sexual minorities.” The team was spearheaded by lesbian lawyer-couple Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Katju.

On a social front, India held its first pride parade, incidentally also South Asia’s first, on July 2, 1999, in Kolkata— called the Kolkata Rainbow Pride Walk. Pride events have now been held in over 21 Indian cities. Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore saw their first pride parades in 2008, and Bhubaneswar and Chennai followed suit in 2009. Kerala’s first march was in 2010 and Pune in 2011. Guwahati was the first to hold a Pride Parade in the Northeast in 2014.

Post the Section 377 judgment

Post the legalisation of same-sex relationships, marriage has been the next battlefront for the community. In India, multiple cases have been filed before High Courts seeking the recognition of same-sex marriages under the Hindu Marriage Act, the Special Marriage Act and the Foreign Marriage Act.

In November 2022, two gay couples filed writ petitions in the Supreme Court seeking legal recognition of same-sex marriages, under the Special Marriage Act, 1954. While the first of these petitions was filed by Supriyo Chakraborty and Abhay Dang, the second was filed by Parth Phiroze Merhotra and Uday Raj Anand.

Similar petitions pending before the Delhi and Kerala High Courts have now been transferred to the Supreme Court. A Constitution Bench began hearing the matter in April 2023, and post a 10-day hearing, the Court has now reserved its judgement. The Union government has been firm in stating that the decriminalisation of same-sex relationships does not signify acceptance of same-sex marriage and that this is not in line with Indian society. It has urged the Supreme Court to leave the matter to the Parliament.

Legislative attempts have also been made after the 2018 ruling. In April 2022, NCP MP Supriya Sule introduced a private member Bill in Lok Sabha to legalise same-sex marriage in the country. DMK MP DNV Senthilkumar S also introduced a bill in the same time frame, requesting that the government frame a national policy for the protection of the rights of the LGBTQIA community. However, in May 2020, an archive, titled State of the QUnion, released by Pink List India showed that less than a third of the 543 Lok Sabha MPs (27.8%) addressed LGBTQAI+ issues in their political career.

In June 2022, the Kerala High Court set a trailblazing precedent by allowing a lesbian couple, Adhila Nasarin and Fathima Noora, to live together after they were coercively separated by their parents. The Court simply asked the couple if they wished to live together, to which they replied with a ‘yes.’

India has also made progress on conversion therapy— a blanket term used for a number of ways, often coercive, used to treat a person attracted to the same sex or of alternate gender identity, to make them heterosexual. It can include the use of psychiatric treatment, drugs, exorcism and even violence. According to AACAP, conversion therapy may exacerbate mental health conditions, like anxiety, stress and drug use, sometimes leading to suicide.

On August 25, 2022 the National Medical Commission (NMC), the apex regulatory body of medical professionals in India, wrote to all State Medical Councils, banning conversion therapy and calling it “professional misconduct”. In a letter dated August 25, it also empowered the State bodies to take disciplinary action against medical professionals who breach the guideline. The letter said the NMC was following a Madras High Court directive. t

The state of LBTQ+ rights globally

LGBTQ+ rights widely vary across the globe, and although several countries have legalised same-sex relationships, fewer nations have legalised same-sex marriage.

Per the ILGA (the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association) World Database, consensual same-sex sexual activity was not criminalised in 129 countries, while 64 countries still criminalise homosexuality, whether by law or de facto. All nations in North America and Europe have legalized same-sex behaviour. In Asia, it was legal in 20 out of 42 member countries in 2020. In 2021, Angola and Bhutan decriminalised homosexuality, followed by Antigua and Barbuda and Saint Kitts and Nevis in 2022. In August 2022, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that the country would repeal Section 377A of its penal code, which criminalised gay sex, while in December of the same year, a Barbados High Court decriminalised homosexuality via an oral ruling.

More recently, in May 2023, the Sri Lankan Supreme Court gave a green light to a Bill seeking to decriminalise homosexuality, saying that it was not “inconsistent with the Constitution.” The Bill can now be taken up for debate and voting by the Parliament.

In 2001, the Netherlands became the first country and, in 2019, Taiwan the first Asian country, to legalise same-sex marriage. At present, same-sex marriage is legal in 34 countries: Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Uruguay. While Estonia’s Parliament passed a law legalising same-sex marriage on June 20, 2023, it will only come into effect on January 1, 2024.

In some countries, gay marriage has been legalised by way of legislation, in others, through judicial pronouncements. Some countries, like Montenegro, have recognised same-sex civil unions, while still not legalising marriage. Civil unions or partnerships provide legal recognition to unmarried couples of the same or opposite sex and grant them some of the rights usually associated with marriage — like inheritance, medical benefits, employee benefits to spouses, managing joint taxes and finances, and in some cases, adoption.

In May 2023, South Korean lawmakers introduced legislation to extend the right to marry to same-sex couples, amending the gendered definition of marriage in the nation’s civil code. Lawmakers in Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand are also reportedly considering proposals to legally recognize marriages or civil unions for same-sex couples.

On the flip side, same-sex relationships remain illegal and proscribed by law in many nations. As of November 2020, six UN member states— Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Nigeria— still prescribed the death penalty as punishment for homosexual acts. There are five additional states where the death penalty may be given, but this is less certain. These are Afghanistan, Pakistan, Qatar, Somalia (including Somaliland) and the United Arab Emirates.

And in June 2023, post the signing of the Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2023, Uganda may have verily added itself to this list.