What the Tova O’Brien employment dispute tells us about the controversial nature of non-compete clauses. Nikki Mandow reports

The woman in the lift sighs wearily. It’s been a big day for staff at the Employment Relations Authority, she says as she heads home. Such a high profile case...

She’s talking about the legal dispute, heard by the authority over three days this week, between TV3’s about-to-be-former political editor Tova O’Brien and her about-to-be-former employer Discovery.

It’s a big deal – and not just for ERA staff.

O’Brien is leaving Discovery – the owner, since December 2020, of what was the TV arm of MediaWorks. She’s joining the radio arm of that same company, the company she worked for before the acquisition – MediaWorks. Her new role will be breakfast show host on the company’s as-yet-unlaunched Today FM radio network.

And it’s complicated.

Discovery wants to enforce a three-month, non-compete clause in O’Brien’s contract. If it wins, it could effectively prevent her joining MediaWorks until the end of April, thereby potentially delaying the launch of the whole new network.

You can't have a news channel without a breakfast slot.

The presence of the clause in O'Brien's contract isn’t in doubt – restraint-of-trade clauses are in many, many contracts in New Zealand and elsewhere. From lawyers to hairdressers, senior managers to baristas.

Most people in that ERA hearing probably have some sort of restrictive provisions in their contracts.

I snuck a look at mine during a break: I can’t steal Newsroom staff, clients or suppliers for six months after I leave, although I don’t have a clause preventing me from working for the competition.

Tova O’Brien does – for three months.

Hours of arguments in the ERA hearing have been expended around issues like whether MediaWorks’ planned morning radio show is actually in competition with Discovery’s morning TV programme, AM, whether being a radio show host is anything like being a press gallery journalist and political editor, what proprietary information Tova as a journalist (albeit a senior one) would have had access to in a newsroom of 230 people, and whether the existence of journalistic sources, information or knowledge built up during her 14 years employed by MediaWorks/Discovery could harm Discovery should she start working immediately for MediaWorks radio.

Punished for leaving?

O’Brien argues her restraint-of-trade is “punitive”, stopping her plying her normal journalistic trade as much to get back at her for a messy parting, and/or to stymie a rival show from starting up, or (perhaps the most likely) to act as a warning for other Discovery staff who might be thinking of leaving to join the new network – and there have been a few already.

Apart from O'Brien, Duncan Garner, Mark Richardson, Lloyd Burr and Wilhelmina Shrimpton will all host shows on the new radio station.

O'Brien says she had a long conversation with MediaWorks’ then chief news officer Hal Crawford about the non-compete clauses when she was offered the political editor role in 2018.

“I was very concerned, but I was given the impression it was industry practice only for like-for-like roles. I believed it wouldn’t be used to punish me for leaving.

“If I had thought it would be used to take me out of my chosen career for three months in any media organisation in the whole of New Zealand, I wouldn't have signed the contract...

“I didn’t predict after 14 years giving it my all, that me going to a completely different role in a completely different organisation and a completely different product, that this was going to be an issue.

“It’s a long time to not be able to do what you want to do.”

MediaWorks argues radio and television are different beasts – so much so that it's not unknown for high-profile journalists and presenters to head a radio and a TV show for competing companies at the same time.

Jesse Mulligan, for example, is one of the hosts of Three’s The Project evening current affairs and entertainment show, while also presenting RNZ’s afternoon slot. Paul Holmes and Mike Hosking worked simultaneously on Newstalk ZB and TVNZ.

A new media landscape

Crawford says he never saw ‘like-for-like’ as being just moving between different television roles. Asked if the restraint-of-trade would have been triggered if O’Brien had been moving to the New Zealand Herald or Stuff, he said he believed it would.

“The media landscape has changed,” Discovery’s senior director of people and culture Kylie Elsom told the hearing. “It’s gone from being very channel focused – TV versus radio – to being very audience focused.”

Same message from Discovery’s director of news Sarah Bristow, who disputed MediaWorks’ claims people are creatures of habit when it comes to their media consumption. You watch breakfast TV, or listen to breakfast radio, but rarely switch your preferences.

“Audience data shows that’s typical in the older demographic,” Bristow says, “but the younger demographic is more readily switching between TV, social media, radio, and podcasts, and it’s that demographic we are interested in. Saying Newshub is purely a TV bus that’s only in competition with TV isn’t accurate in terms of the modern media landscape or consumer behaviour.

“When Maggie from Masterton wakes up in morning she will be making a decision about whether she gets her news fix via The AM Show or via Tova’s news show. And we need as many ears and eyeballs as possible.”

Coincidentally, MediaWorks announced yesterday long-time broadcaster, journalist and presenter Carol Hirschfeld will move from Stuff to be the executive producer of the Tova breakfast show.

Newsroom understands Hirschfeld starts with Today FM in February and MediaWorks isn’t expecting any non-compete clause problems with the move.

You signed the contract – what’s the problem?

Discovery argues O’Brien knew what she was getting into when she signed a contract containing non-compete provisions, and that it’s totally normal for the company to seek to enforce those provisions. Moreover, Discovery says, a three-month restraint is neither unusual or excessive – it’s at the lowest end of the scale.

“My purpose was to give the business a bit more breathing room in case of the sudden departure of senior staff, and reduce the impact of a switch to a direct competitor,” Hal Crawford, a former chief news officer at MediaWorks, and the executive who negotiated the contract with O’Brien when she took the political editor role, told the ERA hearing.

“In television in particular, audiences become attached to individuals. With presenters and high-level people on TV, their appearance represents an investment by the business in that person. Their sudden shift to a competitor can represent a significant blow.”

‘Not worth the paper they are written on’

There is a risk to employers when staff leave.

But here’s what’s so interesting about restraint-of-trade/non-compete clauses. They are widely used, but they are in many cases unenforceable.

“Restraints are anti-competitive,” says Hamish Kynaston, an employment law partner at Buddle Findlay. “Which is why they are considered as unlawful as a starting point – uncompetitive and against public policy.”

In the same way that we are innocent until proven guilty, so we are allowed to move freely from one job to another, without restrictions – unless an employer can prove any non-compete clauses are “reasonable”.

That’s the key word.

“To justify a restraint of trade it must be reasonably necessary to protect a proprietary interest of the employer. If it is wider than is reasonably necessary it will be unenforceable.” – James Cowan

In a paper entitled “Restraints of trade — ‘not worth the paper they are written on’?”, employment lawyer James Cowan from Anderson Lloyd argues as a matter of law, restraint-of-trade provisions are void – both unlawful and unenforceable – “unless they can be established as reasonable”.

“Restraint-of-trade provisions are a creature of contract. In the employment context they represent a bargain reached between two parties as to how an employee will conduct themself after their employment has ended."

“To justify a restraint of trade it must be reasonably necessary to protect a proprietary interest of the employer. Commonly, an employer may have a legitimate proprietary interest in things such as its confidential information, its business strategy, and its customer relationships.

“Even with such a proprietary interest, a restraint of trade must be no wider than is reasonably necessary to protect that interest. If it is wider than is reasonably necessary it will again be unenforceable.”

Uncertain precedents

Sometimes it works out for the employer, as with the case of barista Victor Hsieh. In 2007, Hsieh was working for a Wellington coffee cart chain called Fuel Espresso with a restraint clause in his contract which stopped him from working for another coffee outlet within 100 metres of a Fuel Espresso for three months after leaving.

He must have been one hell of a barista, because when he upped and went to a coffee cart 70 metres up the road, Fuel sought to enforce his non-compete clause. The case went quickly to the Court of Appeal, which ruled in favour of his former employer.

Three months and 100 metres was deemed reasonable.

For the same reason, non-compete clauses are common in hairdressing, Kynaston says.

“It’s a very personal profession. So you might have a three-month restraint within a 5-kilometre radius of the original business. It gives the salon a chance to encourage a customer to try another of its hairdressers, and to try to secure that relationship.

“But a restraint that was, say, 12 months, and covered the whole country, might not be seen as reasonable.”

That’s what happened with Air New Zealand. In 2013, Grant Kerr left a senior management role with Air NZ subsidiary Air Nelson to take up a job with Jetstar. He agreed to six months of gardening leave to see him through his notice period, but argued an additional six months’ restraint of trade was unreasonable.

The Employment Court judge agreed. The court ruled Air New Zealand had a legitimate interest in protecting, through a restraint covenant, its proprietary confidential commercial information – information that was akin to a trade secret – from misuse, Blair Scotland, a principal at Dundas Street employment lawyers, said at the time. But six months was enough for the airline to get the protection it needed.

The Air NZ-Grant Kerr case was a “good wake-up call” for employers, Scotland said.

“You can't use a restraint of trade to try and stop competition – if that’s the reason why you are putting in restraints of trade you’re always going to fall down. The courts’ role is not to protect monopolies and to stifle competition in the marketplace.”

US moves on ‘unfair’ non-compete clauses

Across the Pacific, 2021 was a tough year for restraint-of-trade clauses. As competition in the labour market gets increasingly fierce, federal and state governments in the US are looking for ways to protect workers from unfair restrictions, according to law firm Akin Gump.

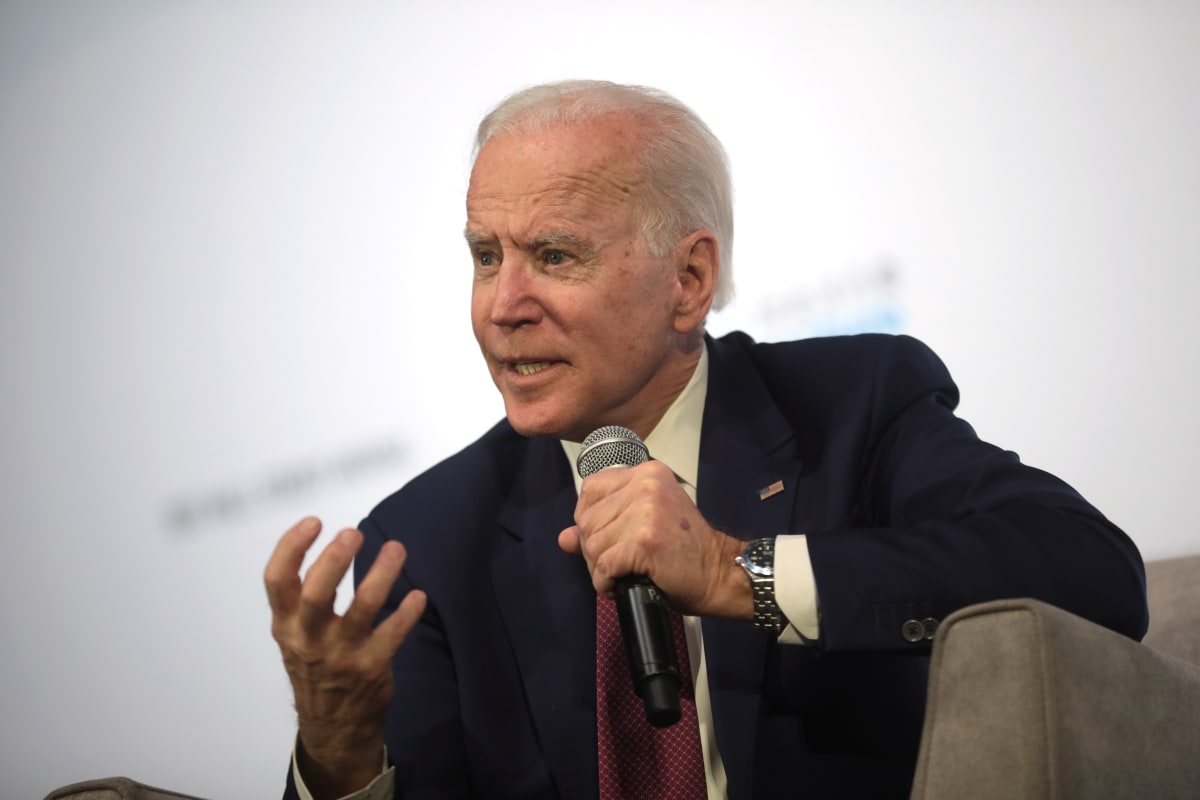

Last July, President Joe Biden signed an executive order encouraging the Federal Trade Commission to curtail the unfair use of non-compete agreements, Illinois introduced a ban on non-compete agreements with any employee earning $US75,000 ($NZ110,000) or less per year, and Washington DC plans to ban non-compete clauses altogether from April this year.

If that happens, Washington will become the fourth US state (with California, North Dakota and Oklahoma) to have effectively banned non-compete agreements altogether outside the context of a sale of a business.

In New Zealand, restraints have been prevalent for years, particularly for senior executives, and arguments or legal disputes are pretty common, says employment law specialist Catherine Stewart.

It’s just they don’t normally involve well-known television personalities and so hit the spotlight.

“It's a contentious area of law and understandably so,” Stewart says. “There are competing interests. Employers are keen to protect their business and employees are keen to be able to move on.

“A company has a legitimate right to protect its trade secrets and confidential commercial information, and an employee has the right to move between jobs and earn a living using their own skills.”

In one of the more lighthearted moments of the Tova O’Brien hearing, she wondered if getting a job in a bar or restaurant would be her only option as she waited for her restraint-of-trade period to end.

MediaWorks director of news and talk Dallas Gurney wondered if Discovery’s broad definition of competing media would stop O’Brien working even “as sales representative at Tokoroa FM”.

How will it end?

Restraint-of-trade disputes inevitably need swift decisions to prevent or allow someone to take up their new job. Although the final submissions were only given to the hearing yesterday, presiding ERA member Marija Urlich has told the two sides she’ll get them an answer early next week.

Which way the decision will go isn’t clear, although as a journalist myself it’s hard to see Tova O’Brien, as political editor based in the press gallery at the Beehive, having access to many of Discovery’s trade secrets and confidential commercial information.

Still the media landscape is changing fast, as media commentator Dr Gavin Ellis told the hearing.

The ERA’s Marija Urlich made much in her questioning of times since the dispute started where communication has broken down between O’Brien and her former boss Sarah Bristow and more recently between MediaWorks and Discovery.

Why didn’t Discovery allow O’Brien to use built-up annual leave as part of her notice period – or even agree to discuss that possibility when she put in a request, Urlich asked Bristow. Doesn’t that add weight to O’Brien’s argument that’s she’s simply being punished?

And on the other side, Urlich asked why O’Brien couldn’t have asked permission to take part in a MediaWorks promotional video, which was put together and aired after the announcement was made about O’Brien’s move, but before her leaving date.

Much has been made of the video – which shows shots of O’Brien and other show hosts alongside upbeat descriptions of Today FM’s proposed programming style.

“To re-imagine what news can stand for,” says one shot with O’Brien in the background. “More hopeful,” says another.

“You did not get permission from Discovery to take part,” Discovery’s lawyer Peter Kiely told the hearing. “There’s a difference between making an announcement of a new job and making promotional video [for Today FM] while you are still an employee of Discovery.”

In hindsight, that video probably wasn’t the most sensible thing for O’Brien to do.

Whatever the outcome of the Employment Relations Authority hearing, it may be that the power of non-compete clauses is waning in New Zealand, as in the US, but perhaps less obviously. Two executive sources from separate industries told Newsroom restraint-of-trade agreements were increasingly seen as unenforceable for all but the most senior employees. Mostly no attempt was made to enforce them; other times they were simply the start of negotiations when someone left a company and provisions were abandoned or watered down, one source said.

Instead companies were relying on extended notice periods to protect its trade secrets and confidential information – potentially including a period of gardening leave, where strategic employees were paid their salary but stayed home.

A few companies were starting to use the fact they didn’t have non-compete clauses in their contracts as a selling point when trying to recruit employees in a tight labour market, one source said.

“In an era of strong competition for talent, restraint-of-trade clauses are putting barriers in place, and in a small market, it’s pretty counterproductive to stuff up relationships with people you might want to work with in the future.”