A UN committee excoriates the Government’s foot-dragging over tortured children. David Williams reports

There are some things that are incontrovertibly true – like Hitler was evil, or slavery was wrong.

Another basic truth, surely, is that children tortured while in state care deserve an apology, adequate compensation and rehabilitation, and justice. Right?

So why are the survivors of the Lake Alice child and adolescent unit, which closed in 1978, still waiting?

Human rights lawyer Frances Joychild QC, who represented some Lake Alice survivors at last year’s Abuse in Care Royal Commission hearings, thinks she knows why.

“Every government of every colour and complexion has failed these people ... so no one will stand up now and say this has got to happen.”

She adds: “It’s just not good enough.”

To be fair, in the 2000s, Helen Clark’s Government paid $12.8 million in total, in two tranches, to 195 Lake Alice survivors, and apologised for unacceptable “treatment”. But 40 percent of the first round of payments went to lawyers, and, despite multiple official inquiries and police investigations, no one has been made accountable.

As survivor Malcolm Richards told the Royal Commission last year: “Our voices were not heard and no-one was held to account. They gave us money and tried to bury it.”

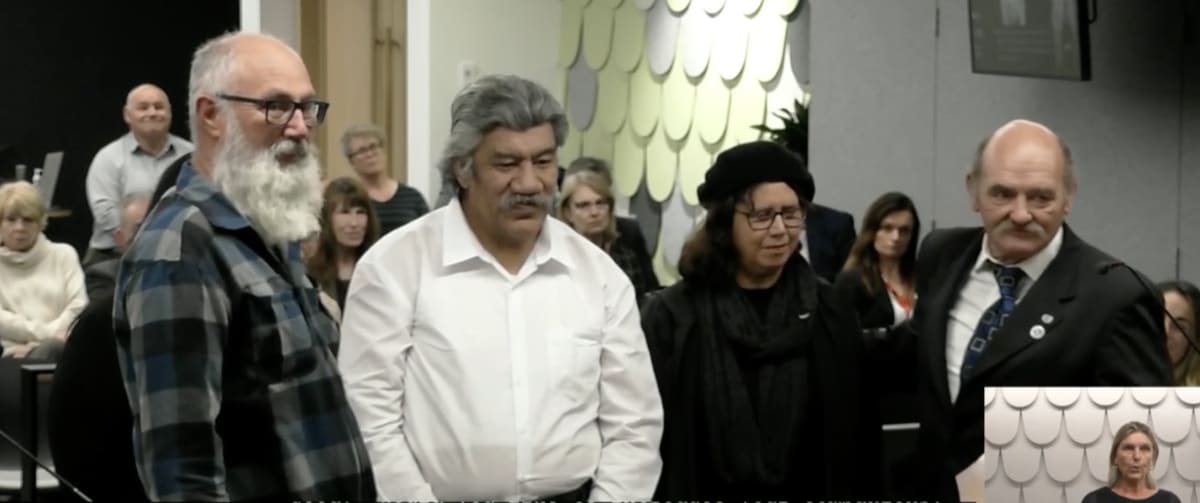

A new chapter in this saga began last week, when the United Nations Committee Against Torture (UNCAT) delivered another scathing assessment of the Government’s response – after a complaint by Richards, who lives in Hastings.

One of the most telling parts of this plot-twist is the response of Government ministers.

Any figurehead can hide behind process, or follow bureaucratic advice to do so. But it doesn’t take great courage to say torturing children is wrong and the Government takes such matters seriously.

Newsroom emailed the offices of Public Service Minister Chris Hipkins, Internal Affairs Minister Jan Tinetti, Health Minister Andrew Little, and Social Development and Employment Minister Carmel Sepuloni.

We wanted to know if Ministers had been briefed on the UN committee decision, and what they were told.

More importantly, we asked: “Given this is the second finding of torture against children at Lake Alice on this Government’s watch, what immediate action will this Government take, if any, to ensure survivors, who were tortured while in the care and protection of the state almost 50 years ago, are getting the rehabilitation, compensation and justice they deserve?”

Hipkins’ office directed us to a communications staffer at the “Crown Response Unit” – set up to handle the Government’s response to the Royal Commission. So we pressed again. Ministers would be well aware of Lake Alice, and the public should know if they’re prepared to intervene, we argued.

The Public Service Minister’s spokeswoman replied: “The Minister hasn’t seen the report yet, so it wouldn’t be appropriate to comment.”

Faced with accusations, from a UN committee no less, of an unacceptably poor response to allegations of torture against children, it could be suggested ministerial silence is inappropriate.

In emailed comments, Alana Ruakere, director of the Crown Response Unit, says: “Officials are considering the implications of the UNCAT report.”

Joychild says there’s a lot the Government could be doing immediately, like providing rehabilitation, or topping up the portion of settlement payments deducted as legal fees.

“But it’s the usual thing,” she says, in exasperation. “They drag their heels. They wait and wait and wait and say they’re waiting for this, and they’re waiting for that.

“These people have been through enough; they’ve been through so much.”

It was this time last year that Richards, now 62, appeared before the Royal Commission.

He described himself as the depressed eldest child in an unhappy home with a violent, alcoholic father. He was sexually abused by the teacher-principal of a small country school.

But none of what happened was a reason to be sent to a psychiatric hospital. The official notes written by the unit’s head, Dr Selwyn Leeks, said he had chronic schizophrenia.

Richards said the only condition he’s been diagnosed with, subsequently, is clinical depression and post-traumatic stress disorder from his time at Lake Alice, near Whanganui.

(Many children admitted to Lake Alice weren’t mentally ill.)

During eight terrifying weeks in 1975, when he was 15, Richards was given electric shocks and painful paraldehyde injections. The unit’s children were in constant state of terror about getting unmodified electroconvulsive “therapy” (ECT) – powerful electric shocks delivered without anaesthetic or muscle relaxant – as punishment.

Children were physically dragged to an upstairs dormitory, from where terrible screaming could be heard. Hours later, they’d be brought down, “half-dead looking”.

“We were threatened with it all the time.”

He recalled one round of ECT punishment after he ran away. It’s worth repeating in full.

“First they shocked me on my legs, causing me to lose control of my bladder and urinate on Dr Leeks, as he was kneeling by me holding the headset on my legs. Then I believe in retaliation for urinating on Dr Leeks he then shocked me on my lower area.

“He shoved the headset between my legs. The pain was unbearable. I still have the burn mark on my penis today. I believe this was caused by the ECT as when I came around my penis was raw.

“Then they put electrodes on my head. The pain was unbearable. My eyes went all fuzzy like an old black-and-white TV at the end of reception. The ECT went on for 10 to 15 minutes.

“It was not just one shock like on the penis. They kept turning the power up until I would have a seizure. I shook violently. I still feel it now. Then I lost consciousness. I still wake up in a cold sweat, my body actually physically hurts in the same places as there, and I accidentally bashed my head on the concrete floor as I thrashed back in pain.”

“I struggle every day ... I have spent much of my life acting like a prisoner always on the run.” – Malcolm Richards

Richards was punished with ECT after trying to hang himself, and was raped while unconscious. “I was left in the cell after that ECT for two or three days, cold, naked with one blanket and a bucket for a toilet.”

His Lake Alice experience has resulted in life-long, debilitating trauma, memory loss, and huge difficulties retaining information. A depressed teen, broken while in “care” of the state, robbed of his potential.

“I struggle every day,” he told the Commission. “I have spent much of my life acting like a prisoner always on the run.”

At age 32, he had a heart attack – something he attributes to stress from Lake Alice. He lives with nerve pain and body aches. Richard is plagued with frequent nightmares, and anger fits.

He’s keenly sensitive to noise, and often loses his train of thought.

It wasn’t until he was 35 that he learned Lake Alice had closed. The news reversed his downward trend – a weight lifted from him, he no longer wanted to commit suicide.

But, as he said, it’s hard to put things behind you when your abusers are free, enjoying life.

To his credit, in the early 2000s Richards started speaking up about Lake Alice. He complained to the police, and even when they closed their investigation in 2010 without laying charges, he continued to call for an investigation – to the Attorney-General, the Office of the Ombudsman, the Human Rights Commission, and the Justice Minister.

Rejected by an impenetrable wall of officialdom, he took his complaint to the UN in 2018 – following the path of another Lake Alice survivor, Paul Zentveld.

The benefit of Richards’ claim taking so long is his arguments, and those of the Government, now sit within years of context.

Since late 2019, when the UN committee handed down its Zentveld decision, the police investigation was re-opened, and a single person, John Richard Corkran, has been charged. (The 90-year-old has pleaded not guilty to eight charges.)

The charges were laid late last year – more than 40 years after the child and adolescent unit was closed, 18 years since the Government invited victims to make criminal complaints, and 11 years after the last police investigation was closed, without charges being laid. Corkran’s hearing is more than a year away.

Police decided it had enough evidence to charge Leeks and another staff member with wilful ill-treatment of a child, but they were medically unfit to stand trial. Leeks died the following month. For many Lake Alice survivors, any chance at true justice was buried with him.

It’s worth remembering the first Lake Alice complaints were filed in 1976, and several official inquiries found no wrongdoing or malpractice.

Leeks wasn’t sanctioned by the Medical Council, and left for Melbourne, where he continued working. Police initially decided Lake Alice staff had shown a “lack of judgement”.

It was retired High Court judge Sir Rodney Gallen who took the claims of survivors most seriously. Though his job was to investigate payouts to victims, he went beyond his brief, interviewing dozens of victims, and substantiating allegations he described as “outrageous in the extreme”.

The UN Committee Against Torture referenced Gallen’s findings when assessing the police’s response to Richards’ complaint in 2000.

“Despite the gravity of those allegations and his particular vulnerability as a child at the time of events and also despite the subsequent findings by a retired High Court judge that electroconvulsive therapy was constantly used on the children as a punishment, the committee notes that, following a police investigation that lasted for over three-and-a-half years, the resulting report, dated 22 March 2010, did not clarify whether the alleged treatment was indeed applied as a punishment.”

The committee itself has, since 2009, been calling for a prompt and impartial investigation into allegations of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of those in state institutions.

Its summary of the Government response is scathing. There have been repeated investigations, pushed along by ongoing public interest. Police acknowledged there was evidence ECT had been used as punishment.

“The authorities of the state party made no consistent efforts to establish the facts of such a sensitive historical issue involving the abuse of children in state care,” the UN committee decision says. “They have also failed to expressly acknowledge and qualify the alleged treatment inflicted on the complainant.”

The Royal Commission’s Lake Alice-specific hearing, last year, was notable for apologies from Crown Law, police and the Medical Council.

There was an “important lapse of time” between the two most recent police investigations, the UN committee said. And the opposing results raised doubts about effectiveness – something police now acknowledge.

(It's no wonder. Its latest inquiry found 136 former child patients at Lake Alice alleged the use of ECT on their genitals and/or as a punishment.)

The Government failed to conduct a prompt and impartial investigation, the committee said, violating its obligations under the UN Convention Against Torture. It has also failed to provide adequate compensation and rehabilitation for torture – claims that were uncontested.

The committee has urged consideration of torture allegations by the courts be “timely” – a hearing isn’t scheduled until late next year – and recommended Richards be given “appropriate redress”, and its decision is made public and disseminated widely.

Mike Ferriss is the New Zealand director of the Citizens Commission for Human Rights, a group aligned with the Church of Scientology. CCHR helped Richards and Zentveld take their cases to the UN.

It’s worth bearing in mind, Ferriss says, the punishment dished out to these young children “you couldn’t imagine in your worst of nightmares”. Yet Ministers seem to have trouble with basic courtesy – writing a letter of acknowledge, praising Richards and Zentveld for their courage in taking their cases to the UN.

Slow progress

Joychild, the lawyer, laments it’s a year since the Lake Alice hearing, and the response is glacially slow. Many survivors are despairing and despondent, she says, and in urgent need of rehabilitation.

“We’ve had people living half-lives, quarter-lives, eighth-lives of their potential, struggling day-in, day-out with terrible post-traumatic stress disorder, memory problems, health problems because of what happened to them.”

Royal Commission chair Coral Shaw says in a statement the inquiry acknowledge Richards, who provided valuable evidence at last year’s hearing. “Our findings and recommendations resulting from our investigation will be provided to the Governor General in the second half of this year,” she said.

The commission can make findings of fault and recommendations for further steps to determine liability, but can’t make findings of civil, criminal or disciplinary liability.

Richards tells Newsroom the UN committee’s decision is fantastic. “At least someone’s come out and said we believe what happened to you was torture and you should be compensated for that.”

But it’s been galling to watch a procession of prosecutions through the courts over historic sexual abuse at Auckland’s Dilworth School, while the Lake Alice saga drags on.

“I just don’t have much faith that the powers that be will do anything, until they’re forced.”

Richards is still fighting the Accident Compensation Corporation to get cover for a “treatment injury” claim – in which ACC found “no evidence of a physical injury”.

The decision was upheld at review and Richards has appealed to the district court.

“We have no doubt that Mr Richards’ has suffered a terrible ordeal during his time at Lake Alice and we want to support him where we can,” Gabrielle O’Connor, ACC’s acting chief operating officer, says in a statement.

“The district court appeal is currently on hold. We have been approached by Mr Richards’ legal representative with new information on this claim and are investigating additional cover.”

Richards says the Government should offer rehabilitation to survivors, and their families, now. “Those children need help, too, but they don't seem to be able to get it.”

An uncomfortable but brutal truth is emerging about Lake Alice. The Government would rather not deal with children tortured in state care, it seems. In fact, it sees them as a terrible inconvenience – a very expensive one.

Yes, the police investigation was re-opened and the Royal Commission into Abuse in State Care has done important work.

But ministers’ silence over the terrible electric shock treatment, and painful injections, meted out to children as punishment, might be worsening the trauma of survivors and their whānau.

Jacinda Ardern’s Government has dealt with many unexpected crises, and has taken deliberate steps to stand close to victims, to hold the hands of the grieving and afflicted. But when it comes to Lake Alice, it appears to rely on bureaucrats to do the thinking for them, from the same institutions that have failed survivors consistently.

Yet again, the children of Lake Alice – and their children – slip through the fingers of the state that was meant to care for and protect them in the first place.

Richards says: “This government says we’re kind, caring and empathetic but I haven’t seen any evidence of that.”