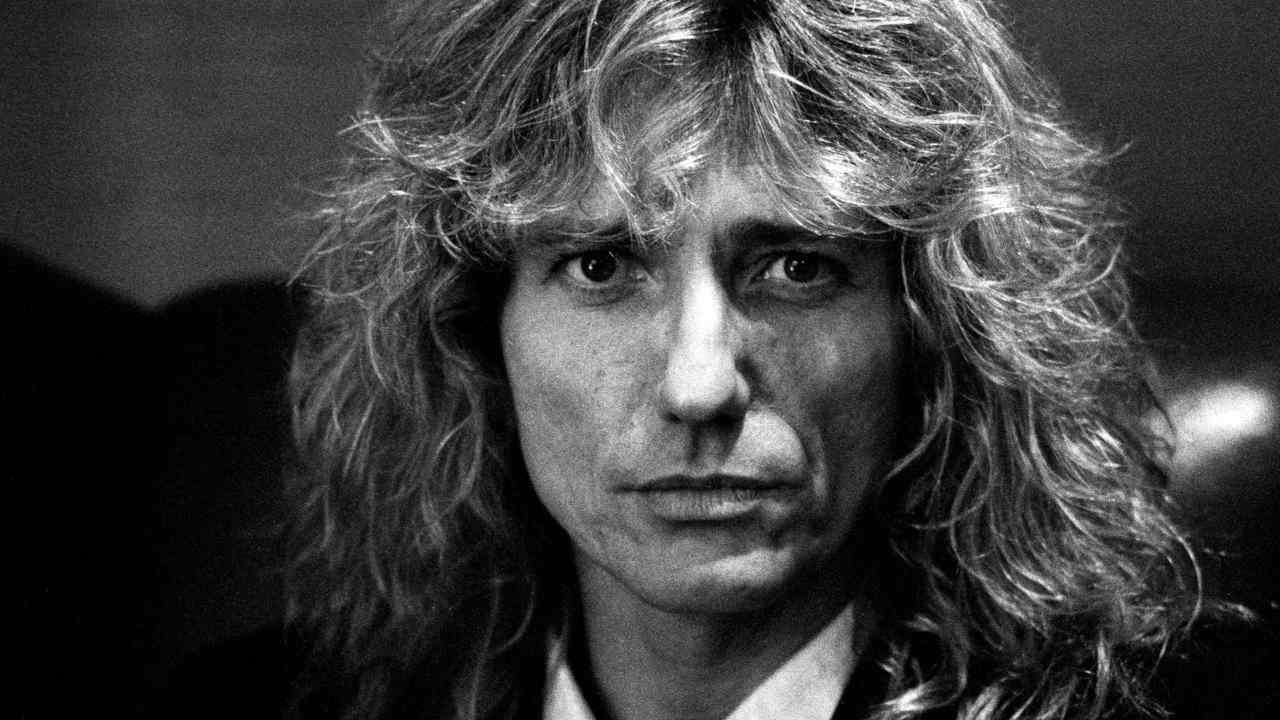

David Coverdale is one of rock’s greatest singers and most charismatic performers – and as an interviewee, he’s not too shabby either. In 2011, as Whitesnake released their 11th album Forevermore, the frontman sat down with Classic Rock for an epic look back over his long and illustrious career. On the agenda: changing line-ups, MTV makeovers classic collaborations, a couple of near-misses and some fantastic music.

Singer, songwriter, thespian, entertainer, raconteur, artist and personality plus, David Coverdale is everything a venerated, legendary rock star should be. You wonder whether the man still has an aura, an X factor, a larger-than-life presence, and within a minute of me seeing him for the first time in 22 years any lingering doubts are smashed to smithereens. Coverdale remains as lustful as ever…

The obvious add-on for that sentence would involve women, but for years now Coverdale has focused those affections and desires on his wife Cindy, to whom he has been married since 1997 and of whom he will speak lovingly on numerous occasions during our day together. No, the lust I’m referring to is one for life. David Coverdale lives life, in its purest sense, as ‘large’ as he can. Up and at the exercise in the mornings, still walking around Lake Tahoe, Nevada, dodging bears, just as he did as a youth in Saltburn-by-the-Sea, North Yorkshire (but sans bears, of course) and most importantly for Classic Rock readers, with a voracious musical appetite firmly re-engaged, Coverdale looks to be on the cusp of an enormous surge of re-popularity and respect.

It is impossible to have a quick chat with Coverdale. He doesn’t bother with trite soundbites, he produces wonderful, meaty feasts of quotes amid plenty more engaging, detailed conversation. Indeed, chats with him invoke big armchairs, fireplaces and a never-ending supply of refreshment going late into the night, resplendent with storytelling, memories and more colour than a rainbow.

“I never like to look back into the past,” he says to me as we sit down to begin our conversation, and if this is true, all I can say is that by the end, Coverdale has delivered an all-star performance in retrospection, history, memories and recollection. And if I tell you that what follows is a heavy edit of the actual conversation that took place, you’ll know just how deep Coverdale went in discussing his most consistent musical love, Whitesnake, and all that came before it.

So let’s start in Saltburn-by-the-Sea, David, and bring people to what inspired you to become a singer.

My mother was a great singer. My mother’s side of the family were the singers, my father’s side of the family were the painters, the sketchers, the artists. But when I went down to my maternal grandmother’s, my beloved Nana’s, that’s where I got my initial musical education. We didn’t have a radio or a record player at home, it was strange. But I heard Elvis Presley and Little Richard on this huge radiogram, and it was just mindblowing.

I would try to emulate their voices, which is more ‘projection’ than the British singers of the time. I discovered that I could project. Any opera singer will tell you they’ll sing from the diaphragm, but all of the amazing soul singers and blues singers sang from the gut. Pure gut singers. You have what I call throat singers, the cleaner voice singers, beautiful voices like Steve Perry or whomever, but mine isn’t that, it’s a gut voice.

Later on, when I jammed with these 15-, 16-year-olds in my town, they couldn’t believe that I could hit the high Stevie Winwood stuff. I had no barriers to say: “No, this is too high.” I didn’t have any barriers or boundaries when I sang Joe Cocker material, you know? I didn’t know that’s not how you’re supposed to sing. I thought that was how people sang. So in that sense I had no blinkers, thankfully.

And then I gravitated towards bands like The Pretty Things and R&B-based bands. I was a huge fan of The Yardbirds, that’s where I learned of Jimmy Page. Hendrix was an immense inspiration and a muse for me, and continues to be. He was harnessing all the stuff that I like, putting blues and soul music in electrifying rock structures. You know, not necessarily wanting to play traditional blues but taking the elements of blues and making ’em work for you, as opposed to becoming a purist in a rigid 12-bar blues band, as much as I love that.

You obviously got this love of the blues and R&B at a young age, but equally you also loved lead guitarists. Why did you not say to yourself: “Bugger it, I should learn this myself”?

I wanted to get a guitar, which I did, for Christmas or a birthday, at a very early age, a cheap kind of plastic thing. But as naïve as this sounds, nobody told me you had to tune it! Or how to tune it. So my fingers’d be bleeding, putting all the appropriate chord shapes on, and they were all absolutely correct… all from the fabled Bert Weedon Play In A Day book. It was really simple with all the chord transcriptions right there in front of you. So I was doing all of that, and it sounded bloody awful because I had no idea about tuning. I had nobody to steer me in the right direction, other than complain how horrid it sounded.

But you were having fun, right?

No, I was miserable because I was not in tune! But as a child, my primary way of self-expressing was drawing. I found out at six or seven years old that there was a school you could go to, to learn how to draw, called art college. And that was my passion from then on.

But I was always singing too, I was singing at school. I have a beautiful Renaissance playlist in my multitude of iPods, and it opens with an old English song called Sweet Nightingale, which I sang rather sweetly, before my voice was bastardised by cigarettes, whiskey and wild, wild women. It was my showpiece at school.

I didn’t realise that singing could be such a vehicle for expression until a chance moment of fate, or whatever you want to call it. I had a music teacher who was ill one day at school, and the only teacher who had a free period at that time was a guy called Benbow, a science teacher. And he came in struggling with the school record player and said: “I know nothing at all about music so I’m just gonna play some records I like.” So he played Sidney Bechet and Leadbelly… and the hairs on my neck stood up, I had an immediate emotional response to this music, whereas a lot of my friends were all sniggering, thinking this was most amusing. I spoke to him afterwards, and he was fascinated that I was getting emotional responses to this kind of music. So he went from there, introduced me to ‘Big’ Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters, who to me is, like Otis Redding, a divine deity. It gave me great inspiration…

I mean, as a kid in Saltburn, I’d take my two fabulous German Shepherd dogs walking, like a pedestrian Ben Hur, and every so often a gang on the other side of the street would be shouting: “Oh, there goes the pop star” and all this. And I’d turn this into a “I’ll show you” attitude inside. It was necessary at a very early age for me to express myself. And it’s difficult when you’re a kid with a bunch of guys, because if you turned round and started to wax lyrical about the sun, ‘like a golden orb in the sky’, you’d have your ass kicked. Things like poetry I kept to myself. Once I learned a couple of chords on the piano and the guitar, those poems ultimately became songs… lyrics.

It’s amazing that you had the balls, and the drive, to then answer an advert to sing for one of the biggest rock bands in the world at the time: Deep Purple.

I’d left art college. I wasn’t on a grant. There was a blight of unemployment in the North of England, so my father, who had been working since he was 14 years old, was on the dole and treating it, understandably, like a holiday. However my mother was working two jobs, and I could see that she was exhausted. So I said I was leaving art college, which broke my mother’s heart because she shared that dream with me. I’d studied to be a graphic design artist and an art teacher.

A friend of mine had a boutique in Redcar, and he asked if I thought I could sell clothes. He said I could keep my hair long. So I became the singing salesman, selling fucking loons, like sailor pants, big flares. I found out I was a pretty good salesman. So everything was fine, I was bringing some money home, and then I moved out of the house. Very young, actually.

One time a guy came in the shop while I was reading the Melody Maker. And he knew I sang and said sarcastically I should go after the job with Deep Purple, and walked out laughing. I went back to reading and right there in the Melody Maker was a picture of Jon Lord sitting at the organ, a bit Monty Python like, with a little line that said: “Deep Purple are still looking for a singer and are considering unknowns.” That was all it took.

So I went round the corner to a public telephone box, and called a guy called Roger Barker, who managed the local band I was with, and I asked if he had any contact numbers for Deep Purple. He gave them to me. They wanted a demo and a photo, so I sent them something I’d done when I happened to be very drunk. Ian Paice was the one who collected my tape from the Purple office. And apparently he called Ritchie [Blackmore] and said: “I think I’ve found somebody. He’s rat-arse drunk but he’s got a good tone.” So they set up an audition for me. They never asked me to do any Purple songs at the audition, but Ritchie said: “Is there anything of ours you want to do?” So I sang my version of Strange Kind Of Woman, more expressive, moving around the melody rather than following the guitar, or whatever, and Ritchie came over and said that’s how he’d heard it when he first wrote it. Which was really cool to hear, as you can imagine.

You brought a different style to Purple.

I brought what I felt was ‘blues rock’ element stuff. Obviously I wasn’t coming in with 12-bars, I was coming in with rock licks because I loved Hendrix, I was raised on licks, for crying out loud, and even if I can’t play them, I can sing ’em! So Ritchie and I would mostly write the music and then introduce the band to it. They’d add their incredible personality and character, which made it Deep Purple. I mean, Jon Lord’s left hand was an immense part of the Purple sound. Oh… that sounds a bit risqué. And then, to keep the peace, I’d exchange licks with Glenn [Hughes]. But really it was best when Glenn sang one song or I sang one song, rather than confuse the audience with “I’m singing a line, he’s singing a line”. It got silly. And I said to Glenn after I’d left, we had this immense opportunity to be the Unrighteous Brothers of rock. And we pandered to each other’s egos. Oh, well… that was then.

Blackmore quit in the end and, rather than shrinking away, you came back even stronger. But at the same time you didn’t go for a ‘big’ guitarist off the bat, you brought in Tommy Bolin. Do you think this first exposure to guitar genius and ego made you a tad gun shy for seeking the ‘mega-six-string-star’ for a while?

John Kalodner [Whitesnake’s A&R man in the 80s] made a really astute observation. He said: “I can fully understand after working with Blackmore why you worked with some of the earlier Whitesnake guitarists.”

You mean like Bernie Marsden and Micky Moody?

They were very great guitarists, great musicians, and I truly appreciate what they brought to my life, but – and I mean no disrespect at all when I say this – cos they could play all the legit stuff, but they didn’t have the image of ‘guitar hero’, like Blackmore, they didn’t have that ‘Hendrix’ showmanship. It didn’t bother me, but on reflection maybe it was more accommodating to me at the time because Ritchie did wield an immense amount of power. I genuinely learned a lot of incredibly positive things with Ritchie that I still utilise, and I witnessed a lot of stuff that made me uncomfortable, that I didn’t ever want to do or be a part of again.

In terms of human interaction?

In terms of that, yes.

When you left Purple, were you immediately fired up and ready for the next phase?

I was so worn out by it, everything was amplified a thousand times, and I was just shattered by the entire three-year experience. So God bless my mother. I went home after the last Liverpool show and she left me alone and didn’t grill me like she normally would have at that time in her life. She left me to recover from my total fatigue. I’d fall asleep in a chair in front of the fire, I’d wake up and there’d be a corned-beef sandwich and a cup of tea. I’d have a bite or sip and then I’d fall back asleep. Once I got past the fatigue, I clearly knew I didn’t want to be a part of that anymore.

Having recovered from the Purple phase, how would you describe the early Whitenake blueprint?

I suppose Northwinds was the early blueprint, but there’s a lot of that stuff I’d forgotten until very recently.

I confess to not knowing much about Northwinds, so let’s look at that early Northwinds into Whitesnake phase then, 1976-’77.

The early Whitesnake blueprint? Well, among other things, the early Allman Brothers were huge for me. Look at the structure, of two guitarists, one doing extraordinary slide guitar. That first Allman Brothers album [The Allman Brothers Band] lit me up immensely. I wanted to utilise all those elements, and more. I’ve always loved writing songs and I continue to do so to this day, but with Purple we’d extrapolate the songs and one song could last half an hour. So with Whitesnake, I specifically wanted to harness all the stuff that I enjoyed, but under the wide, creative umbrella of this band. And I did not want to be known as a one-trick pony. And the guitarist or soloist had to express themselves within the structure and continue exploring the narrative within the song. Not just ‘widdly diddley’ all over the place, all the time, you know?

How did it go from Blackmore leaving Purple to you bringing Ian Paice and Jon Lord with you to Whitesnake?

It looked like a grand masterplan from the outside. But I just had a great connection with Ian and Jon. After Jon had joined, with his immense presence and energy – amazingly, as I’d been given an embarrassingly small amount of money to create the band – Ian Paice came to see us at an early Hammersmith Odeon show, and apparently he had had a couple of glasses and was heard to say: “God, they could be better than Purple.” Jon told me this and I said: “Do you think he’d be interested in coming on board with you?” And to me, that was the actual beginning. When Paice came in to do the Ready An’ Willing album with us at Ridge Farm Studios, that was it. And with Neil Murray, of course, being the stellar bass player he is. This was the real musical beginning of Whitesnake for me.

Was there ever a doubt for you? Was there ever a fear that it could just explode into egos?

Nah. Though there were times. Whitesnake wasn’t about all that. We had lots of obstacles to overcome. There wasn’t time! Purple was great, and without Purple I wouldn’t have been able to have started this big adventure. But from the first show I ever did with Whitesnake, it was much more naturally me than it was with the Deeps. This was natural David Coverdale. You know, there’s got to be an assortment of reasons to be invited into Whitesnake. It’s not just that you’re a great musician. There’s the personality, too. We do a lot of homework before we even tell anybody that we’re thinking of them. One of the immense strengths of the early Whitesnake was the shared sense of humour. We had more laughs than was legal to have.

Inspired by?

Everybody. Jon’s very funny, Bernie’s very funny, Micky was very funny. Sorry, Neil! It was all of these things that no matter how many obstacles, we always managed a laugh. Don’t forget, I started Whitesnake at the height of punk in London, so nobody at the time was backing my fucking snake! But the sense of humour was amazing and supportive and helped break down just barrier after barrier after barrier.

What about the rumour that you turned down Black Sabbath.

There were three things I was offered after Purple. Tony Iommi, God bless his cotton socks, was calling me a lot, and I was saying: “Tony, I love you but I know what I want to do.” I love Tony, I just don’t see him enough. I think Sabbath are amazing at what they do, you know, but it wasn’t something that I wanted to do. Uriah Heep was another one. Lovely guys and all that, but I knew what I wanted to do. The most interesting one for me is mostly unknown: there was a management guy who got in touch with me and asked if I’d be interested in singing with Jeff Beck, Willie Weeks, Andy Newmark, and Jean Rousseau. Jean Rousseau was the keyboard player with Cat Stevens. I would have dropped pretty much everything for that. This was right before Whitesnake in 1976, or early ’77.

Coming back to the Marsden/Moody-era Whitesnake, you took some time out between Come An’ Get It and Saints & Sinners to be with your daughter?

Yes. It involved my family. At the time, every four steps we took forward saw management decisions make us slide back six steps. It was just getting too much, and it wasn’t improving economically. We were going very deep, playing to 15,000 people on some nights. We played one show in the Midlands where Robert Plant came to jam with us, and the audience response was so amazing, I forgot to invite him on stage. There are astonishing emotional memories of those times, but the reality was there wasn’t the financial rewards coming in. And my daughter’s serious illness told me very clearly that this was the only time I should have my head in my hands and be worried about being unable to change the circumstances. It was necessary for me to experience that so I could stand up and be counted, and give me the backbone to make life-affecting decisions. I put Saints & Sinners on hold to be with her.

She had, within a two-year period, bacterial meningitis and then Kawasaki Syndrome, but the doctor at Amersham Children’s Hospital was amazing. He never gave up. He just paced up and down looking at every book. Kawasaki Syndrome’s cured by a course of adult aspirin, but during recuperation the chance of cardiac arrest is very significant. Jesus! But she came through with no problems at all and she’s amazing now. A stunning mother of two gorgeous daughters. So, yes, it gave me the balls to turn round to my manager then and say: “I’m done.” And I went to my lawyers and said: “Get me out of there.” And it cost me… Oh, yes… it certainly cost me.

So it was an epiphany, basically.

Yeah, it was huge. Again, because compared to my daughter’s health it was a nothing decision. It was a contract. My daughter’s well-being, not being able to do something about that, is understandable, but this was different. And it translated into making the biggest change. It cost me more than I had at the time. I was made responsible for the entire Whitesnake debt. It cost me over a million dollars, which I didn’t have, yet I was back in credit in a matter of months. After we resolved the situation, I agreed to finish Saints & Sinners.

So Whitesnake got to a point where you realised that in order for the band to fulfil what you saw as its full potential, it needed more presence?

Yeah, it needed Cozy Powell and it needed John Sykes. I took Thin Lizzy out on a European tour before we lost Phil [Lynott], so I could have the opportunity to check him out. I’ve always been able to see potential and I thought very quickly: “He has great potential.” But nobody else in the band was interested; nobody wanted him. Cozy didn’t want him. Martin Birch [producer at the time] didn’t either. They didn’t think he would fit in when I flew him over to Munich, where we were doing the Slide It In album. And at the same time I was talking to both Michael Schenker and Adrian Vandenberg.

So you tried to sign Adrian Vandenberg about five times, right?

Once, actually. Well, he was a big fan and we met when I was touring Europe with Ozzy Osbourne. We were in the hotel bar afterwards and I met Adrian and his girlfriend; this was in Holland… Utrecht, I think. I felt both Adrian and Michael were very similar in that beautiful classic, melodic soloist style, but I wasn’t sure I wanted all the other stuff that came along with Michael at the time. I’d heard Adrian’s song Burning Heart, and thought it was a great song. And, of course, I called Adrian right at the time he was having an American hit with Burning Heart.

So, Adrian reluctantly said no, but we agreed we’d maintain contact and he told me that it was the most difficult decision he’d ever had to make. I told him not to worry, that we’d get there sooner or later. Which we did, of course. So I went back to talking to Sykes. The biggest problem with John and I was personality clash, that’s all. Simple. You know, musically it was very fine. But personality-wise, it was a crash collision…

Were the ‘creative tensions’ fruitful?

John and I would get on very well at times. We’ve all heard the stories for years about my favourite British group, The Who, and the antagonistic energy between Pete and Roger, like the antagonistic aspect between Keith and Mick in The Stones. That’s fine for them, but I’m not remotely interested in that in my life. I want to have fun. I want to enjoy my life and be amused by it all, you know? I love that John and I wrote great songs, but I don’t believe that chapter of the band would have lasted long and I don’t believe the album would have been as successful as it ultimately became without the other members who actually toured with me promoting it.

So the six-cent question is obviously… do you still speak with him?

There was a sort of ‘reaching out’ back in 2001, 2002 where John basically said he would love to work on some new stuff with me. I was initially interested. I was cutting some demos in yet another rental house in Tahoe. So there was this reaching-out kind of thing that a mutual friend arranged. We ended up speaking several times, which was really nice and pleasant after some of the horrible energy between us for so many years, but ultimately I felt that we’d been our own ‘boss’ for too long. He’s a fine player and I truly do appreciate what he brought to the table. Make no mistake, he did well, too.

But you don’t do grudges, right? You’re not a grudge holder.

You know, when I’ve finished a book, if I haven’t enjoyed it, then I give it away. I don’t keep it in the library. So no grudges… not anymore. For example, Bernie [Marsden] and I had some ugly stuff go down over several years in assorted interviews. But we had a chance meeting in Heathrow a couple of years ago. We sat down at Starbucks in Heathrow Terminal 4 and chatted about stuff in between flights, and it was lovely; we reconnected from that. We’re in quite regular contact and it feels a helluva lot better than being bitter and resentful for both of us.

Let’s address those early LA days for you in the mid 80s. How do you look back on them now?

We wrote the 1987 songs in the south of France, in a small villa about 30 miles outside of Saint Tropez in a town called Le Rayol. In those days it was a sleepy little community. We were there for a while. I have never been back so I don’t know if it’s changed. Afterwards I went to London, closed down some things, flew to Los Angeles and moved into the Mondrian hotel on Sunset Boulevard, while looking for a place to live. I knew the owners and the people who ran the hotel and they said: “Well, why don’t you stay here?” So I got a kick-ass bachelor penthouse overlooking downtown Los Angeles. And I had a scary good time. I swear to God, if you are a bachelor, hotel living’s the thing. I was there for three years. Three fun-filled years.

Wow, America obviously suited you.

Well, there was nothing going for me in London. There was huge negative energy about me in the press. My first marriage was over, so there was nothing to keep me there. We’d done the Slide It In tour back then, we broke merch records and everything, yet I lost three grand. Doesn’t sound like a lot, but it gave me a clue I needed a tour the size of America to be able to pay for Whitesnake. A couple of big bands who shall remain nameless, who owed me favours from other parts of the world, wouldn’t let me special guest or anything to get over to America. And then Ronnie Dio, God bless him, contacted me and got us over. Unfortunately we only did half a dozen shows but we sold 200,000 copies [of Slide It In, which would later sell over four million records] and achieved a ton of promo and made a lot of people aware of us, so radio and press were prepared for Whitesnake’s follow-up. So, when you add MTV, it was primed and ready and just took off on an astonishing trajectory.

Let’s detail these Geffen years a bit more.

I’d met David Geffen and John Kalodner, and I was fascinated by them. One reason was because I’d been surrounded by a mentality that if you make five pounds profit let’s go to the pub. Whereas David Geffen said to me: “If you can make five dollars profit, why not 50? If 50, why not 500? Why not 50,000, why not five million?” And I found this very interesting because Whitesnake is an expensive enterprise, and everybody wants to do more than just pay the mortgage or the rent, you know? I embraced that philosophy and it applied well in my career perspective.

It is an important aspect not only to be able to finance a band, but for the people involved to see a significant reward for their labours. I knew that if Whitesnake was going to make an impact in America it would take more than me sitting in London taking pissy, pointless shots across the pond. I had to take it on from the inside. And it worked astonishingly well. I sold embarrassingly large amounts of records in a three- to five-year period. The hardest thing was the physical and emotional geographical distance from my daughter, which was nothing less than awful.

And it was early on during the Geffen days that the Whitesnake personnel changed, right? With John Kalodner offering suggestions?

Kalodner was great for me at that time, as I was for him. We were on the Slide It In tour that we had with Ozzy in Europe, and Kalodner said, rather insensitively: “You’ve gotta get rid of these musicians, and Cozy’s gotta clean up his act.” Interestingly Tommy Aldridge was Ozzy’s drummer on that tour. Kalodner also said he knew why I had a certain style of guitarist in the band, because I unconsciously didn’t want to go through the Ritchie Blackmore experience again. So he was basically articulating what I knew inside. And at that time the dynamic drastically changed between Micky and I. I’d wanted to promote Micky into being a star, and I don’t think he wanted it. Fair dues. You can only go so far at times with certain people. Some people simply are happy where they are. And that’s fine.

When it came to reinventing the look of the band, was MTV of some importance to you?

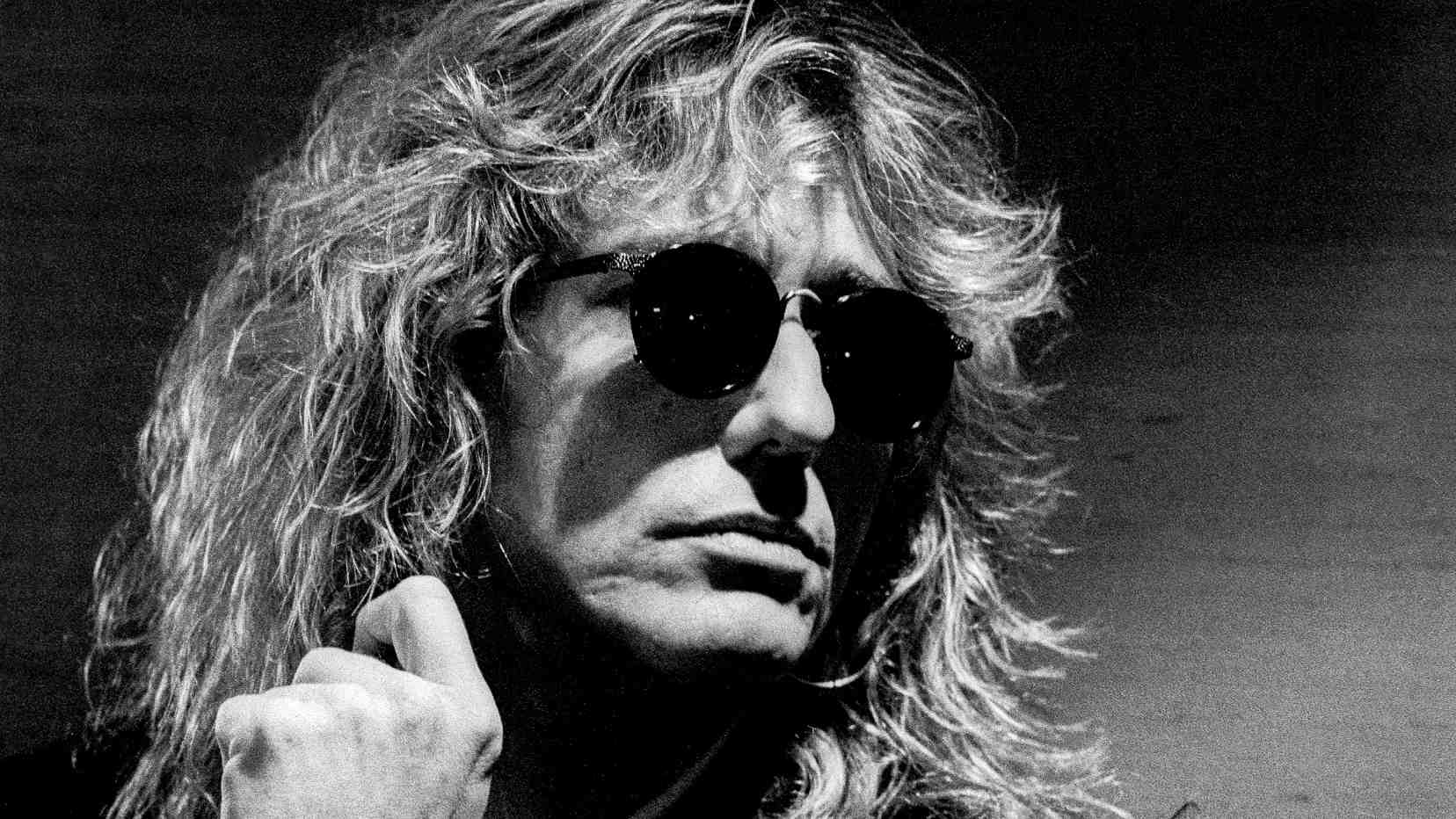

Yeah, I suppose so. But, really it just unfolded that way. I can’t remember it being a conscious decision, to be honest. It looks clever in hindsight. One time I was in the Mondrian hotel in ’85. I can’t remember who I was watching on MTV, but I thought: “Well, I’ve still got a full head of hair but it looks really boring compared to those guys.” So the night before the Still Of The Night video, I had gone in to see the video director Marty Callner’s wife, a beautiful woman called Aleeza, for highlights, just like little touches. And suddenly I’m blond! In those days it was a chemical rinse, so when I said, “Put it back how it was”, she said, “I can’t, your hair will come out in clumps.” In this sexy Israeli accent. Now when I see Still Of The Night it really isn’t that blonde, but it was just, you know… it looked different. I’d been blonder in Deep Purple.

The videos, the ‘rebirth of Whitesnake’ album… they just exploded.

I was about three million dollars in debt when the 1987 album was released, and within three months I was in credit. That’s how big it was, and how quick it happened. Another reason I think I got on with Kalodner was that he understood songwriting and he understood me. Old-school A&R guys will be pulling fucking teeth trying to get a band to understand that songs need hooks, not just riffs. And that’s something that I’ve enjoyed for years. Still do.

Let’s reflect a little on the largesse of that overwhelming, multi-platinum success Whitesnake had in the 1980s.

In America it’s very strange, because celebrity and excess can be celebrated. It’s extraordinary to me. Because the other side of the coin with me is that I’m an intensely private man. And once that huge kind of ’Snake mania was going on over here, Tawny [Kitaen], my second wife, and I, we couldn’t go anywhere without being mobbed. We were chased down Sunset Strip in my white Jag, and I’m going: “This is not on. This is not what I’m here for.” I still had a beautiful estate here, a penthouse there. But this invasion of my privacy wasn’t on. That’s when I decided to get the hell out of Dodge and move to Lake Tahoe.

You hit a great central point, which is obviously that relationship [with Kitaen, a model who appeared in Whitesnake videos and soon became Coverdale’s wife]. I imagine it became as much a part of the band as your life, and that perhaps that pissed you off?

No, not at all. I’m truly grateful for everything that’s helped me get the music out there. But yes, it was exhausting. When I did the 1987 record it was plagued with problems, personality issues and my health. Advantages that were taken when I was too ill to do anything about it. So anybody who took advantage of me during my unfortunate time, I let go. [This was when Sykes and Coverdale had their major falling out – Ed.]

Was the beginning of that to do with a vocal issue? Didn’t it cause a potential threat to your singing career?

Yeah, it was from a deviated septum. Horrible, but in truth after the surgery my vocal range increased. Go figure.

But you had the success, and then all of a sudden, Adrian Vandenberg had to be replaced after you’d literally just finished writing together.

I wrote great songs for Slip Of The Tongue with Adrian Vandenberg. They’re very different from how we originally envisioned them because Adrian unfortunately couldn’t be featured on the record as he had injured his wrist while we were getting ready to do the initial tracking [The two remained, and remain, solid friends – Ed.]. So a lot of the songs took on a different shape when Steve Vai came in.

I’d wanted Steve Vai while I was still working with Sykes. Sykes was unenthusiastic, as you can imagine. But I thought Sykes and Steve would have had an incredible playoff together. Steve’s a beautiful guy, an astonishing player, he’s the Paganini of rock. Was he a Whitesnake guitarist? I don’t know. But I’ll tell you one thing, when you see the Live @ Donington 1990 DVD, Vai is as much a ’Snake as anyone has ever been up there. He is fucking dynamite. You see what Steve Vai is all about. He celebrates every moment he’s on stage. Vai’s an astonishing musician, an astonishing player, and I’m delighted I had the opportunity to work with him. But was it the Whitesnake people generally think of? Maybe not. There wasn’t a lot of blues element there, no. My private circumstances at the time also became a serious distraction of significant proportions.

During Slip Of The Tongue?

Yes. One example. I’d be standing in the studio, ready to sing, and I’d get an urgent phone call. I’d say: “Tell her I’ll call her back.” And then suddenly: “No, no, it’s urgent, you’ve got to take the call.” So I’d come out of the studio after being in the zone, pick up the phone, and be told the wallpaper samples hadn’t arrived. That was the crisis. That was the reason to pull me out of focused work. And this just kept going on and on and on, and it just alienated any kind of commonsense aspect of a relationship. It was screamingly obvious that I didn’t want to be there anymore, and that very quickly it had become such an intense goldfish bowl we were living in, and a luxurious fishbowl at that, but there was no joy in it. It was no fun.

So you’d wrung the joy out of the whole situation?

It had gone, yes. It was probably like crushing 10 or 15 years into an intensely short period of time. But I don’t talk about certain things because I’m not holding any bitterness or resentment. To be honest, I don’t even think about it. About that time. Everything happens for a purpose. It’s all of these personal choices we make, and they’re usually immensely good lessons for us to learn. Had I not had those experiences with former paramours, I wouldn’t know how astonishingly good I’ve got it now with my wife [Cindy]. We’ve just passed 20 years together and hopefully another 40 or whatever I’ve got left, I will hopefully spend together with her.

When did you find it all grinding to a halt?

It was at the Budokan in Tokyo [September 1990]. I gave all my stage clothes to Cathy, my wardrobe assistant, and said: “Burn ’em, get rid of ’em, I’m done.” The band had no idea I’d filed for divorce from Tawny. In my mind it was my farewell performance. I hadn’t stopped working for three or four years. Non-stop. And at the end of that last Tokyo show, I got all the guys together said: “Look, I’ve filed for divorce, I’ve gotta take a break and see if I still want to do this.” I told them if they got an opportunity to go elsewhere, please take it. Please don’t be calling me saying: “Are we gonna do anything?” Because I won’t take the call. And I hugged ’em all and thanked ’em for a great tour.

You know, anybody from the outside would go: “Jesus, you’re a multimillionaire. You’re married to this beautiful video vixen. You’ve got multi-platinum albums and a great house, all the stuff that people think is the ultimate goal.” But I wasn’t enjoying it. I needed time to sit back and go: Is this still fulfilling to me? Is this what I want to do?

I’ve done that a lot in my life. When it gets to the point where I’m confused and out of balance, I have to stop, take stock and review… I’ve retired more times than Frank Sinatra! So I went back to Tahoe and met my future wife for the first time when the last thing I was looking for was a relationship or a commitment. We still celebrate the eighth of November – it happened very soon after I had returned to Tahoe from the world tour. Probably six weeks after the Donington show. Love Will Set You Free, the first single/video from the new record [Forevermore], is about that meeting. When we held hands for the first time, it was just electrifying. And the patience that she showed with me as I took off all of this emotional armour I was wearing, all these self-defence mechanisms, and got me to the point where I have more joy with her than I’ve ever had in my life. I do everything I’m doing now with her blessing. She’s my partner. But at that time, I didn’t know what I was going to do. There was no addiction but I had to stop to clean up. It was emotional addiction, where I had to stop everything I was doing and clean up my life, because it was out of control.

It would appear some grounding was necessary but then you got the dream call, right?

Then I got a fucking call from [booking agent] Rod MacSween going: “Do you mind if I give your number to Jimmy Page?” Which was just way too interesting for me to pass. It was only a few months after putting the ’Snake on hold. And I said: “You know, Jimmy, I’m going through what I know is going be a knockdown, drag-out divorce. I don’t want to be distracted. If you don’t mind, let’s put it on the back burner for a while. But yes, I’d love to meet with you.” He was coming over to have a big meeting with Atlantic Records, and it would have been rude had I not met him in New York. So we met, connected fabulously, went for a walk away from the lawyers, stepping out in Manhattan… and we stopped fucking traffic, Steffan! You want to talk about memorable moments! Cab drivers shouting: “You guys gonna work together?” Honking their horns. We looked at each other and said: “This could be fucking special. Let’s do it.

And at that point had you had enough of a mental detox?

The best thing you can ever do is make decisions to change what’s not making you fucking happy. And I’d made that decision. Don’t forget, I had the incredible grounding quality of this beautiful relationship [with Cindy]. And I took the creative side of working with Jimmy Page very seriously because I’d been a fan and an admirer of Jimmy Page since way before Zeppelin. Page is a lovely, lovely, lovely man to work and to socialise with.

And was it all you hoped it would be?

Yeah. It was fabulous. When Jimmy and I sat down to write, I’d jammed like a motherfucker the day before he was flying into Tahoe, and we utilised every idea on my ‘ideas cassette’. It was the best medicine. Put yourself to creative work. You know, work you enjoy, while you’re sorting out the other shit.

Did you feel any pressure because of the Robert Plant comparisons?

It was heartbreaking for me that that took place, and I regret any negative words I said about that. I love Robert and I’m a great admirer of Robert, and we’re from very similar schools. But I don’t do comparisons. That’s up to you [the media] guys. It’s like when I get into Eastern Europe and the first question’s inevitably: “What was it like with Deep Purple?” Like my life has been downhill since! You know? Man, so far from it. And I’m usually completely unprepared because I don’t think about it. I don’t think back to last week. But it’s not a memory thing, it’s choice.

The Coverdale Page album was a hit, very successful.

It was great. The problem was we didn’t tour.

And why?

I think mistakes were made on both sides, and it just didn’t happen. We did half a dozen Japanese shows, which were just great fun. It was great to work with him, and I wouldn’t change a thing. But close to three years we worked on that [album] and all for six shows. I really love to perform, I love creating songs with the intention of taking them live.

So from that project, you enter the Restless Heart and Into The Light era.

So after three years and six shows, I wanted to form, courtesy of Viz’s The Dog’s Bollocks… Pride Of Tahoe, a kind of Mad Dogs And Englishmen kind of band with girl singers and stuff. I had a whole cassette of all these songs that I wanted to do, from The Allman Brothers, Little Feat, Muddy Waters, Hendrix. Just to go out and play, naïvely have fun and bring the fun too.

So I’m preparing this ‘under the radar’ European tour, and EMI decide to release Whitesnake’s Greatest Hits, which went on to sell a million in the US. It also shifted a remarkable 100,000 records in two days in England, getting to number four in the chart! So I’ve got EMI on the phone to me, Rod MacSween on the phone to me, saying: “You gotta call it Whitesnake.” I said: “I haven’t formed a Whitesnake.” You know, it was Adrian and Denny Carmassi, and I said this isn’t what I would do as Whitesnake. So we went out and toured and the band were terrific, but I never considered it a Whitesnake thing, you know?

When it came to Restless Heart, the executives at EMI agreed with me after Coverdale Page that I could work as David Coverdale, they agreed I was gonna do a solo record. Restless Heart also started out as a solo record, and during the making of it, near the end, once again the guard [at EMI] changed and they said: “We want this to be a Whitesnake record.” I was like: “Fuck, it’s not a Whitesnake record!” It was too late to start over, so we made the drums louder, we made the guitars louder. If you listen to that album and Into The Light, they’re like brother and sister albums.

We should also discuss Good To Be Bad, which I know you have a soft spot for.

I’m a fool for Good To Be Bad. I think it’s a cracking Whitesnake record. Doug [Aldrich, guitarist] and I had much fun writing and recording it. A couple of those songs manifested as I came out of my morning meditations and sat with my son’s two-thirds-size nylon string guitar and just came out so naturally. I love the lyric ‘Can you hear the wind blow, signifying changes’. Some of those songs are big and very relevant for me. And now with Forevermore I can hear all the relatives. All the brothers, sisters and cousins of Good To Be Bad. That album was on its way to being very, very, very successful, but the German label went belly-up. But what was amazing to me, when I got a little bit of distance after finishing it, was how it was like a greatest hits of Whitesnake. It’s as if a song could have come from Ready An’ Willing, a song could have been on the first record, Trouble.

What of your much-publicised vocal problems? [Coverdale had to leave the stage in Red Rocks, Colorado on August 11, 2009 during a show] They were rumoured to be potentially career-threatening?

I have no idea where that rumour came from. It was an aberration, like a skier breaking his wrist. I just needed to rest my voice. I had no medication, no antibiotics. It was just something that happens. Well, it was surprising for the style of vocalist I am that something like that had never happened before. All the wear and tear, et cetera. These weren’t vocal problems that were prior or are ongoing. It was an isolated case of getting what looked like a blister [The technical term for which is ‘severe vocal chord edema’ – Ed.]. I mean, I thrash my vocal cords up there. And as you can hear from the new record, that hasn’t changed. The only thing that could cure it was rest, taking a break.

The sad thing was I had to leave the stage three songs into a set, in front of a very enthusiastic audience. But the huge bonus was I ended up finding two of the best throat specialists in the world – who were at that show and run their operation out of Denver. They have this phenomenal clinic specifically for voices, the sinus, and the upper respiratory. They had a digital camera down my throat and that was it. Had I not made that call to stop the show and that thing had burst, we probably wouldn’t have been sitting here talking. They simply gave me a list of vocal protocols, what to avoid, though being a singer I did most of the recommendations anyway. So there’s not a problem, thankfully.

When did you start meditating, by the way?

It’s got to be about 12 years ago. When I first started in college in the 60s everybody said, “Oh, let’s go and meditate” – which was basically fucking smoking cannabis! But I’ve been told repeatedly by people close to me through the years that “meditation would suit you”. And I always had this excuse: “Oh, my mind’s way too busy.” It is, and I’ve still got a three-ring circus going most of the time. But I control it much better. I would distract myself with this and that and the other for a great deal of my adult life while learning about ‘this’ philosophy and ‘that’ aspect of spirituality. I’ve never been drawn to a particular religion but I firmly believe in God, the Supreme Being. I don’t preach, I preach [only] the Gospel of the ’Snake. But I find it’s invaluable to me. I begin every day with meditation, and if there’s anything that I could say to people about the most incredible accessory or tool that I’ve found in my life, it’s meditation.

You’ve stated that you don’t necessarily spend a lot of time looking back on your past, and that Whitesnake albums are all personal documents telling something of where you were at that time in your life…

It’s a fascinating thing. The title track of Forevermore is an absolute celebration of eternal love. It’s a love song that is about a love that can transcend lifetimes. Forever love. Everything that I’ve gone through in my life has all been preparation to be able to recognise what I have, and what is special, and that I intend to regard this as precious and continue with it. It’s the perfect Whitesnake song. Whitesnake Forevermore. Now there’s a tattoo. It wasn’t specifically written as a title track, it just resonates.

I’ve had some very interesting, reflective times this year with [producer] Kevin Shirley, Glenn Hughes and the former manager of Deep Purple, whom I reconnected with after many, many, many decades. And hearing the fabulous work Kevin Shirley did on the remix of Deep Purple’s Come Taste The Band, it’s impossible not to take these little slices as diaries and reflect back on where I was at that time. So that’s been resonant. Musicians I haven’t seen for 40 years… suddenly I found in a garage some tapes of the bands Rivers Invitation and The Fabulosa Brothers, the bands I was with before joining Deep Purple. And they very generously sent them over for me to listen to, and so suddenly I was right back in this record shop that Alan Fearnley, the guitarist, had in Middlesbrough. And that’s where we would rehearse! It was a little corridor! On either side were racks of great vinyl records, and we’d be set up in a line down the shop. A Hammond organ at the end, drums next to him, going down through the shop…

It’s going be very interesting for you this year, given that you will turn 60, and given how it’s often an age people choose to spend engaging in some heavy reflection.

Well, for me to sit down and hear myself still fucking wailing on Whipping Boy Blues and songs like that, at 59 years old, is a testament that I must be doing something right!

Yes, but it seems to me that you, of all the people that I know in rock’n’roll, could have quite a 60th birthday bash if you wanted to. You could happily fill the room with protagonists, collaborators, lovers, fighters, all of them, and thoroughly enjoy the volume, colour and pageantry of it all.

Decades have always been interesting for me. My 50th was fan-fucking-tastic! My wife threw a beautiful small dinner party for me with my closest friends and teachers. It was beautifully low-key.

You certainly seem even more about staying away from the ‘buzz’ during the metaphoric off-season than ever before.

Celebrity is meaningless to me. I’ve been there, I’ve done that. You know if it helps me introduce my music to more people, that’s fine. But as my wife said, if you are touring [when the 60th hits on September 22], Jasper and I are coming out. Perhaps this is the scenario. I’ll be standing, hopefully in some fabulous hotel, looking out over Paris or London or Rio on my birthday, just thinking what a lucky bastard I am, which is one of the things that resonates repeatedly with me. This band right now, with Doug, Michael Devin and Briian Tichy being just an absolute wrecking crew, and Reb who is possessed by his instrument, well… I cannot wait to bring this band on the road because it’s going to be very, very fucking exciting! So look at me, here I am doing what I absolutely love, with people I love and respect around me. Are you kidding? This is the stuff of dreams!

You’re just an incurable romantic in all aspects of life, aren’t you?

Oh, absolutely! Totally! In the art I love, the books I love, the movies I love, and I love human beings. It’s always a shock to me how cruel we can be and how incredibly loving we can be.

I would love to see you in the same room with the actor Brian Blessed. That would be some dinner!

[Laughing) I’ll tell you what, you should have been in a room with John Hurt and me doing Shakespeare, drunk out of our minds in Munich! But again, it’s about passion, it’s about enjoying life. And I think that’s very important for people to understand, that there is a root passion that informs what you do. All we have to do is live it to the fullest.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Whitesnake: Forevermore