In the early 1950s, when Hank Aaron was 18 years old, he got his first contract as a professional baseball player with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. Within months, his contract was sold to the Boston Braves. The rest of that narrative is well-documented history.

Soon after, the Clowns signed another player to replace Aaron, chosen to expand the team’s audience appeal. Her name was Toni Stone (born Marcenia Lyle in 1921). She was the first woman of any race signed to a professional baseball contract, although she had traveled the country as an itinerant freelance player for years. She claimed she once got a hit off the great pitcher Satchel Paige, but that anecdote has proved unconfirmable.

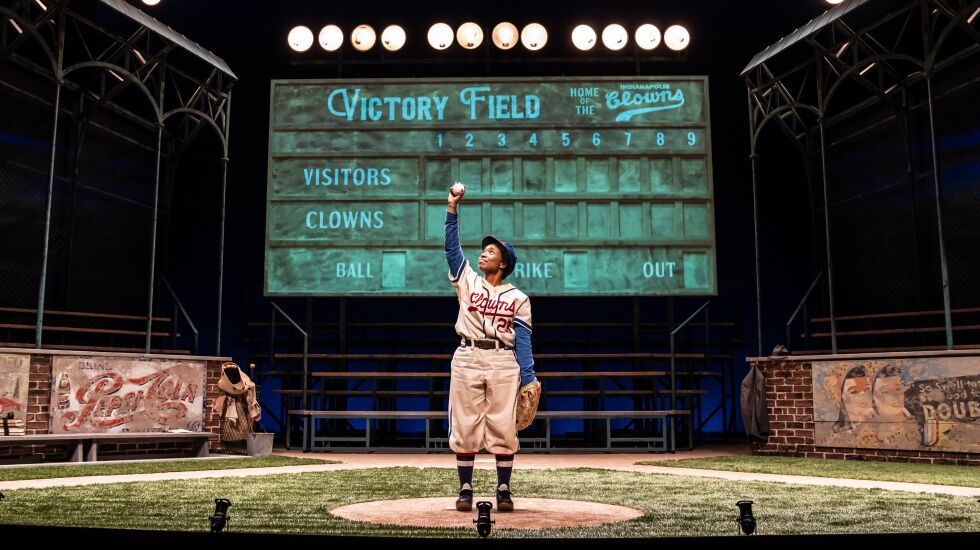

Lydia R. Diamond’s play “Toni Stone,” now running at the Goodman Theatre, provides a compelling character study of a woman driven to achieve what she was told she couldn’t. Diamond is too crafty a playwright — she wrote “Stick Fly” and “Smart People,” both produced in the last few years at Writers Theater — to think of this as a historical document, even though she breathes plenty of life into the historical.

Stone, played by Tracy Bonnar with superb conviction and a plethora of personality, narrates her own biography. She’s a reliable narrator, but not a linear one. “I am prone to ramblin,’” she tells us at the start. “Never could tell a story from beginning to end nice and neat.”

So instead, Diamond weaves a fascinating but also messy, not always cohesive, story about fitting in where you don’t, and not fitting in where you do, and maybe vice versa.

She’s backed by her teammates with the Clowns, a ragtag group of gifted ballplayers, all played by talented performers. Among others, there’s the resident intellectual Spec (Edgar Miguel Sanchez) who quotes W.E.B. Dubois and Harriet Tubman; the flirtatious but almost certainly gay Elzie (Joseph Aaron Johnson), and the resentful, sometimes threatening Woody (Terence Sims).

Travis A. Knight plays Stretch — whose job as coach mostly involves driving the bus deep into the night looking for places that will welcome Blacks — but also plays Syd, the white owner of the Clowns, who insists on giving the fans what they came for by convincing pitchers to let her hit. And Jon Hudson Odom plays an alcoholic outfielder and also Toni’s baseball-despising mother. But more prominently, he also gives Toni a loyal confidante as Millie, a sex worker with a royal bearing and a perspective on profession and personal identity. Are you what you do?

Under Ron OJ Parson’s direction, and with help from movement director Cristin Carole, the baseball games come to life with relatively minimal choreographed movements, swinging bats aided by Andre Pluess’ sound design of well-timed swooshes and cracks. Set designer Todd Rosenthal gives us a beautiful, period-ballfield background, and then conveys a bumpy bus ride through the use of bleachers.

To the production’s credit, you do get a sense of the unglamorous life of traveling teams and understand the passion it took to play a game that paid little and demanded sacrificing of dignity, such as staying calm when the crowd shouts racist epithets, or running to the bus for a fast escape after beating a white team, which was itself a more dignified option than throwing the game as they were expected to.

The most purely entertaining parts of the play are when Diamond explores Toni’s befuddlement over being courted by her future husband Alberga (Chike Johnson) —resorting, as she does, to reciting baseball stats — and when the players step forward to demonstrate the showmanship that caused people to compare the Clowns to the Harlem Globetrotters.

For me, in addition to Odom, the standout ensemble member is Kai A. Ealy, who, as famous player/entertainer King Tut, shows us what a minstrel-style performance looks like, funny and disturbing simultaneously.

But the play does lag at times as the narration gets heavier and Diamond explores the darker side of Stone’s journey, trying but never finding an ending that brings it together, or that even quite tracks.

But thematically, “Toni Stone” is many-layered and deeply complex. It’s a thoughtful contemplation on identity and dignity. It takes a single character’s obsession with baseball and stirs it up, fairly, with the social quagmires of race, sex and sexuality. And then stirs it up again with individual choices about one’s profession and one’s happiness.